“Who knew that the big story of 2023 would be the decline of China?”

This is what one prominent Chinese academic told me, on a recent trip to China. Like many scholars in the mainland, he didn’t want to be named for fear of career reprisals. He is a strident nationalist, who has long enjoyed tweaking the noses of Western visitors with his talk of a multipolar world. Now he fears that China’s leaders may have inadvertently engineered a return to American hegemony through their own incompetence.

His mood is so bleak that he talked of taking early retirement, and leaving Beijing entirely. The gloominess he evinced was echoed time and again, in my discussions with dozens of thinkers from some of China’s top universities and think tanks. Not everybody was as depressed or negative, but in over two decades of visiting China I have never encountered so much frustration and lack of hope. After Beijing’s economic exuberance in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008, and again in the early Covid period of 2020-21 where China’s zero-Covid approach allowed a V-shaped bounce back, the atmosphere among Chinese economists is now sober.

Almost everyone in China agrees that the economy isn’t doing well. But the reasons behind their pessimism are different from those posited in the West. They think the potential for growth is high, and they are less concerned by structural factors — demography, debt, export controls — that Western analysts obsess over. Instead, some feel that China might be stuck in a trap of its elites’ own making, where the successes of the China model in recent years could counterintuitively create the most problems in the future.

Several argued that opposition from the U.S. does not pose the biggest economic challenge, but rather the miscalculations of China’s own leaders. Very few were willing to speak on the record, and the private conversations with a few dozen Chinese economic thinkers that this essay draws on are not necessarily representative of the population as a whole (like most elites in China, they tend to be slightly older and mostly male). But what they said spoke to a deep-seated malaise that is strikingly different to the bullishness of just a few years ago.

China might be stuck in a trap of its elites’ own making, where the successes of the China model could counterintuitively create the most problems.

From the dictatorship of economists, to their depression

One economist explained the national mood to me by means of an allegory. “Imagine a tale of two people,” he said. “One is in prison, but he knows that everyone is doing all they can to get him released. The other is free, but convinced he may be arrested at any moment. Which one do you think is happier?”

He left the answer hanging, but the implication is that the first person was China over the last several decades, under Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao: a developing country on the make, full of problems but bursting with optimism and solutions. The second person is Xi Jinping’s China after Covid: powerful, but insecure. A country that has made it to the first rank of nations, but sees enemies everywhere and is doing all it can to eliminate risks.

(China News Service/YouTube)

Some of these sentiments can be explained by the downturn during Covid, and even more so by the brutalizing policies deployed to contain it. Some of those I spoke to had found ways of defending Zero-Covid, coming up with an intellectual rationale for its excesses. But now they wonder, what was it all for? Zero-Covid policies involved a level of intrusion in everyday life that many found intolerable. It turned them into prisoners in their homes, destroyed their livelihoods, and killed tens of thousands of businesses while many in the rest of the world had greater freedom and better vaccines. When the policy was abandoned, in December 2022, it was without any preparation; the ensuing chaos killed hundreds of thousands of people. And almost everyone I spoke to had been personally affected: one economist I talked to had a near-death experience himself, which caused him to fundamentally rethink his priorities. The callousness of the authorities in the face of all these trends left many with a kind of PTSD.

The woes of the economists go beyond shared pandemic trauma. Two decades ago, economists in Beijing and Shanghai had a spring in their step. Their influence over China’s development from the 1980s onwards had been so great that disgruntled political scientists referred to the “dictatorship of the economists.” Chinese economists educated in elite Western universities had imported ideas which lay at the heart of the opening and reform process that Deng Xiaoping started and Jiang Zemin moved forward. By the turn of the 21st century, a new generation of political economists was challenging the neo-liberalism at the heart of that orthodoxy, with demands to rebuild the state’s fiscal capacity, redistribute resources, and build a welfare state that could help stimulate domestic demand. In the 1990s, the orthodox economists, such as Fan Gang and Zhang Weiying, branded them the “New Left” — coined to discredit them, but as the political mood shifted these thinkers, including Wang Hui and Cui Zhiyuan, embraced the label and called their critics the “New Right.”

Both groups pointed to champions of their ideas within the hierarchy of the Chinese Communist Party. The Shanghai clique, who rose to prominence under Jiang Zemin and were associated with market economics, provided political protection for those on the New Right; the Communist Youth League (a political faction under Hu Jintao that drew people from more humble backgrounds and inland provinces, more interested in equality than marketization) backed the New Left. These economists wandered the corridors of Zhongnanhai, the seat of power in Beijing, and played a role in writing five year plans. I profiled many of them in my 2008 book What Does China Think?, and showed how the ideas of free market liberals like Zhang Weiying for greater privatization were clashing with those of more statist thinkers like Hu Angang for the ears of Party leaders.

That has changed. For many Chinese academics, the physical lockdowns of the pandemic have gone hand-in-hand with an intellectual lockdown, as the sphere for public debate has steadily shrunk. Economists are no longer encouraged to write and research about many current issues; they are ordered to teach Xi Jinping Thought in the classroom; and they struggle to get more sensitive articles and books published in Chinese. One of those I spoke to had spent the best part of ten years writing a book on communist ideology, only to find that no publisher was willing to bring it out. Several used to enjoy political influence in the permeable space between think tanks, universities and Party bodies. But the appetite for an intellectual back-and-forth has dried up. In its place are writers who can’t get published; economic advisers whose advice is no longer sought; and experts on international economics who find the government is more focused on national politics.

For many Chinese academics, the physical lockdowns of the pandemic have gone hand-in-hand with an intellectual lockdown, as the sphere for public debate has shrunk.

The price of success: pivoting from growth to security

One of the reasons why economists were so influential in the 1980s and 1990s was the key injunction of the opening and reform era: growth is the main task. But in the Xi Jinping era — now that China has become, by its own definition, a moderately prosperous society (小康社会) — priorities have shifted. The main task today is security (a word that Xi Jinping mentioned over 50 times in his opening address to the 20th Party Congress in October 2022). As a result, business elites are losing faith, and Xi’s securitization of everything has transformed thinking about globalization and economic policy.

One influential economist — Zhang Yuyan, Director of the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences — has coined a new term to signal the economic threat from the U.S.: guisuo. He translates this as “confinement,” and argues that Washington’s goal is not to decouple from China’s economy, but to stop China from catching up in terms of advanced technology.1 The word guisuo (规锁) has two components: “rules” and “lock.” According to him, Washington’s goal is to lock China into technological backwardness by developing new domestic rules (such as export restrictions and the CHIPS act) and international institutions which shut China out of key technologies.

Others are trying to develop a new economic philosophy for this securitized age, in the context of what Xi Jinping calls “dual circulation”. This guiding principle, introduced in May 2020, posits that instead of China having a single economy, it has a bipolar economy with two centers that interact closely: an internal component (domestic circulation) and an international one (external circulation). Under Xi’s vision, “internal circulation” is the priority, and external circulation a subsidiary. His goal is to make China more self-sufficient, an autarky, and to diversify its economy away from a reliance on the West (the sanctioned telecommunications company Huawei called this the “spare wheel” strategy).

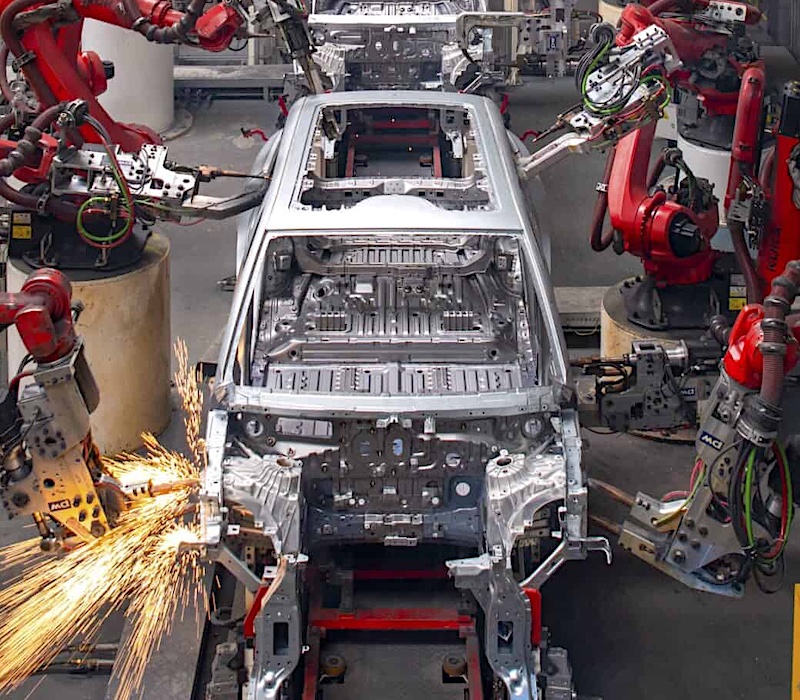

Since the financial crisis of 2008, China had been trying to reduce the importance of external demand as a driver of economic growth by boosting domestic consumption. Some economists, such as Huang Yiping, have pushed the idea of freeing up domestic circulation by removing barriers for production to “flow” around the economy. That includes removing restrictions on the sale or leasing of land, as well as restrictions on local governments protecting state-owned industries from competition by companies from other provinces. Beijing already wanted to move up the value-chain, manufacturing higher value-added products and investing in innovation under the Made in China 2025 policy. Following pressure from the Trump and Biden administrations, Xi’s government also pursued self-sufficiency in key technologies that the U.S. is trying to restrict access to, notably semiconductors. And in the light of massive economic sanctions against Russia following its invasion of Ukraine, China is seeking ways to reduce their own exposure to Western sanctions. Zhang Yuyan has also coined a term for this: the “yuan-ization” of the Chinese currency, instead of its internationalization.

A second dimension of the “dual circulation” strategy is to increase the dependence of other countries on China. This has been named the “body-lock,” in an analogy to wrestling. By binding Western companies into Chinese supply chains, Beijing can increase its leverage. And by linking other countries up with its hardware and software, it can push Chinese standards and norms in the new digital realm. This strategy may become most evident in Taiwan, where Beijing is using its influence over the economy to shape the island’s politics.

Many of the economists think that dual circulation has already taken some of the sting out of a worsening geopolitical environment. Trade with the U.S. has not actually gone down in real terms. Although access to top-of-the-range semiconductors is restricted, China is increasingly producing mid-range versions (and it still has access to finished products, such as Apple devices which are still mostly made in China). Rather than facing de-globalization, many argue that globalization is simply changing. Since the U.S. policy of “de-risking” (downgraded from decoupling) started during the Trump years, a new phenomenon has emerged of “indirect trade” in certain hi-tech sectors — where the U.S. reduces trade with China but increases it with ASEAN countries, chiefly Vietnam, who in turn receive investments from Chinese companies who import and assemble the products as intermediaries. As a result, a form of triangular globalization has emerged.

In spite of some changes at the margins, both China and America are likely to maintain their dominant roles: China as the workshop of the world, and the U.S. dollar as its dominant currency. Both will continue to depend upon one another, even as mistrust between the two grows. It is this atmosphere of distrust that fuels China’s new security-first economic policy — one that is obsessed with maintaining control, and with stopping the outside world from undermining China from within.

Now that China has become a moderately prosperous society, priorities have shifted. The main task today is security.

The best of economies, the worst of economies

The critical question behind all this is how well the economy is actually doing. Among the Chinese economists I put this to, the most common answer was “very bad.” But they reject the Western analysis of peak China as a result of demographic issues, an absence of domestic reform and a negative international environment. Instead, they point to China’s structural advantages. Of its 1.4 billion citizens, only 400 million are middle and high income. The remaining billion are still low income — hundreds of millions of them in the countryside — and can still be brought into an urban industrial economy, boosting domestic demand as well as economic growth.

The key challenge for China is stimulating that demand. China has a lot of fiscal head room to do this. Its central government debt to GDP ratio is only 60%; interest rates are low. Several economists called for a 4 trillion yuan stimulus package, echoing what China did in 2009 in response to the collapse of Lehman Brothers. But they want the money to be spent in new and different ways: less on roads and industrial infrastructure, more on social infrastructure including old peoples’ homes, nurseries and hospitals.

The demographic situation is not the problem that Westerners think, they feel, at least in the short-term. China is not desperately short of workers: there is 20% unemployment for young people, and it is always possible to bring more workers in from the countryside. Economists are also positive about advances in new technologies. China is overtaking Japan as the world’s largest car exporter this year, and the Chinese company BYD is the world’s biggest manufacturer of electric vehicles, with sales that leave Tesla in the dust), and it is making progress in AI. Economists at Tsinghua and Peking University told me they have built models which show that China’s growth potential for the next decade is between 5 and 6% annually, through a combination of advanced industry upgrades and clean energy technology.

In short, Chinese experts feel the economic fundamentals are not as bad as Western debate suggests. Where they are really pessimistic is about the politics. “The United States can’t stop China’s growth,” one economist said, “only the stupidity of our leaders and the sycophancy of their advisers can do that.” Chinese economists think the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is so focused on its own de-risking of the economy that it is creating an even bigger risk: economic stagnation. In their eyes, there have been a series of unforced errors by the central government. In 2015, they crashed the stock market. In 2017, they created a crisis of deleveraging. In 2020, they took aim at the tech giants, with a Party campaign against Jack Ma and Alibaba and the cancellation of Ant Group’s planned IPO. And now the housing market has been driven down by the government.

The policy agenda to turn these things around would not be so complicated — but the CCP doesn’t want to embrace it. “People thought that as the economy developed we would need to open up our politics”, said one economist. “But,” he sighed, “that’s not the way it works. It is people and ideas that change the world, not economic forces.” The biggest problem is confidence: from entrepreneurs and foreign companies; from students who need to return to their homes; and from consumers who need to make purchases. These deeper societal and political problems cannot be fixed with a change in the interest rate.

Chinese economists think the CCP is so focused on its own de-risking of the economy that it is creating an even bigger risk: economic stagnation.

Modernization with Chinese characteristics

Not everyone is despondent — some political scientists and International Relations experts are leaning into the current mood by becoming political “influencers.” Several professors have reinvented themselves as ultra-nationalist social media stars. One professor who I got to know two decades ago for his erudite studies of international relations, Jin Canrong (金灿荣), now has 2.7 million followers on Weibo, posting explanations of current issues. For him, engaging with the general public is a calling. He also thinks that it allows professors to have a different kind of influence in Xi’s China, and believes that the senior leadership keep a close eye on the social media debate.

He spends a lot of his time attacking the West, calling on Beijing to be tougher, boosting various initiatives that Xi launched, and fleshing out ideas on “modernization with Chinese characteristics” — namely, that after China’s economic breakthrough in the reform and opening era, now China needs to break through intellectually and spiritually.

One of the economists I talked to mocked this approach with a powerful allegory. He told a story about a prodigious athlete who was born with one arm, who breaks every world record and wins every competition. Other athletes, awed by his speed and prowess, queue up for operations to get their own limbs removed — but they don’t realize that the athlete’s prowess on the running track is in spite of, rather than because of, his missing arm.

There has been a revival of interest in certain circles in Yang Xiaokai, a distinguished economist who passed away in 2004. Shortly before his death, he developed a concept coined by late 19th century American economist Thorstein Veblen, the “curse of the latecomer,” into an analysis of Chinese modernization. Yang’s theory of “latecomer’s disadvantage,” presented in a conference at the Beijing-based Unirule (Tianze) Institute of Economics in December 2001, critiqued an emerging conventional wisdom that China had benefited from the blessing of being a latecomer into the world economy, which allowed it to compress its modernization by copying technologies and practices from other countries. Professor Yang warned that advantages for latecomers eventually turn into disadvantages, when a nation copies technologies and techniques rather than the systems that produced them.

Emerging economies absorbing technology from developed nations, he argued, can make huge progress really quickly. But this progress will eventually slow, and will regress if not backed by a “good system.” Yang was warning against the illusion of latecomer advantage blinding Chinese leaders to the “backwardness” in their economic and political systems — which he felt they should have tackled alongside their embrace of new technologies. For him, the biggest danger is to think that it’s China’s own greatness which has allowed it to advance, rather than the ideas it has copied from other countries, which have different philosophies and institutions. In other words, if Chinese leaders thought that their success comes from uniquely Chinese characteristics, they could end up in a real mess.

Yang’s arguments were eloquently put, but I’m not sure that his critique captures the extent to which China’s accomplishments come from a blending of Western and Chinese ideas. Many other nations that were backward in the late 1970s copied Western technologies and economic policies, without transforming their countries in the way that China did. The way that China’s economists turned their country into a massive laboratory for political and economic innovation, through ideas such as dual track pricing, was a key driver for China’s advances.

Sigmund Freud, once wrote a short essay called “On those wrecked by success,” explaining: “People occasionally fall ill precisely when a deeply-rooted and long-cherished wish has come to fulfilment.” Many Chinese economists today would think Freud would have little trouble diagnosing Xi Jinping’s China. After decades of promising to turn China into a moderately well-off society, the nation now faces a series of challenges that derive from its very success. It has reached the limits of its old economic model, and become so powerful that it faces a geopolitical backlash.

Xi thinks China succeeded because of Marxism-Leninism, and is doubling down on it. But it is striking how many of the most innovative features of the modern Chinese economy are being driven out by an attempt to create a more centralized system of governance. Xi is, above all, motivated by a desire to rejuvenate the Chinese nation — but in the process, his policies could lead to stagnation, and prevent China from fulfilling the destiny he seeks. ∎

- Zhang, Yuyan, “Understanding the ‘Great Transformations Once in a Century’.” International Economic Review, no. 5 (2019), pp. 9–19. ↩︎

Mark Leonard is Co-founder and Director of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), as well as the Henry A. Kissinger Chair in Foreign Policy and International Relations at the U.S. Library of Congress. He is author of What Does China Think? (2008) and The Age of Unpeace (2021), and contributes to Foreign Affairs and other publications on geopolitics, China and EU politics.