Peter Goullart (1901-1978) wasn’t the first outsider to discover the charms of Lijiang in China’s southwestern Yunnan province. And if the crowds of tourists that thronged the destination when I last visited over Spring Festival were any indication, he won’t be the last.

Jade Dragon Snow Mountain towers above cobbled streets, visible from almost every section of the old town. Wild rivers cascade down nearby slopes and through the surrounding valley and villages. At 8,000 feet in elevation — but on the same latitude as Florida and Saudi Arabia — Lijiang’s natural bounty has for centuries supported diverse communities, including the Nakhi ethnic group (sometimes Sinicized as “Naxi”).

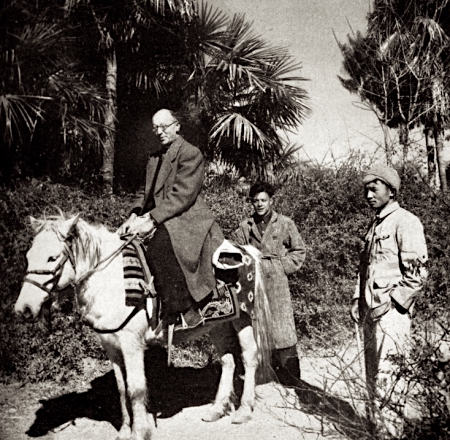

It was here, among the Nakhi people, that Goullart — born in Russia, but raised in exile in Paris and then Shanghai after his family fled the Bolshevik revolution — finally found a home. Goullart arrived in Lijiang in 1942 to organize small-scale rural enterprises as part of the Kuomintang government’s Chinese Industrial Cooperative movement, and lived there until 1949 when he once again was forced to flee a revolution, as the Chinese Communist Party and their supporters began asserting control.

In 1955 Goullart published The Forgotten Kingdom, a memoir of his time in Yunnan. It is both a personal reflection of Goullart’s efforts to become part of the Lijiang community, and also includes chapters that are more ethnographies of the Nakhi and the other groups in northern Yunnan, as well as descriptions of Lijiang and the surrounding area. Goullart writes:

In the beautiful valley of Likiang, then still untouched by the complexities and hurry of modern life, Time had a different value. It was a gentle friend and a trusted teacher, possessing, there, a magical property which not only I but others had noticed. Instead of being too long it was too short; the days passed like hours and the weeks like days; a year was like a month, and my ten years spent there went by like one.

It was an earlier work of fiction, James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, that made the name Shangri-La synonymous with fantasies of a utopia hidden somewhere in the mountains of Asia: a place where ageless sages and innocents, unsullied by contact with the modern world, guarded mysterious repositories of wisdom. While the Chinese town of Zhongdian, about 100 miles northwest of Lijiang, may have changed its official name to Shangri-La in 2001 to attract tourists, the real inspiration for Hilton’s hidden mountain idyll remains a mystery. There are those in Lijiang who argue Hilton modeled his creation on the writings of Joseph Rock (1884-1962), the Austrian-American botanist and writer — and acquaintance of Goullart — who penned a series of dispatches in National Geographic Magazine from Lijiang in the 1920s and 1930s.

The title of Forgotten Kingdom seems a nod to James Hilton’s fantastical Shangri-La, and one suspects that Goullart or his publisher knew this when it came to market the book. We can compare the descriptions of fictional and real valleys:

By accident he stumbled into the rocky defile that remains today the only practical approach to the valley of Blue Moon. There, to his joy and surprise, he found a friendly and prosperous population who made haste to display what I have always regarded as our oldest tradition — that of hospitality to strangers.

James Hilton, Lost Horizon (1933)

Descending from the pass, the loveliness of the valley hit me with staggering force, as it always did when I made this journey to Likiang in springtime … the weather, warm but with a tinge of freshness that came from the great Snow Range dominating the valley. Mt. Satseto sparkled in the setting sun, a dazzling white plume waving from its top.

Peter Goullart, Forgotten Kingdom (1955)

Yet unlike Hilton’s fiction, the memoir is the real story of one outsider’s effort to become a part of a vibrant community. Goullart remains something of a role model for anyone who has moved to an unfamiliar place and sought acceptance from the people who already lived there. He archly notes that those who kept aloof from the people of Lijiang (one suspects he had in mind the sometimes anti-social and high-handed Rock) would never find acceptance among the Nakhi:

In courting friendship with a Nakhi a good deal of sincerity, sympathy and genuine affection was necessary, and also patience. They were very sensitive people. The Nakhi possessed no inferiority complex, but neither did they suffer a show of superiority in anybody.

Goullart also had the self-awareness to know that despite his efforts, he would always be an outsider. He knew he was an interloper: in Lijiang representing a central Chinese government that might have felt nearly as remote to the people of Yunnan as the court of St. James. Keeping Yunnan — a lifeline between South Asia and the wartime capital of Chongqing — out of the hands of the Japanese was crucial to the Chinese government, but administering the province, long an unruly frontier with only nominal supervision, proved as difficult for the Republic of China as its dynastic predecessors.

Tasked by the KMT government with establishing rural industrial cooperatives in mining and agriculture, Goullart succeeded despite the challenges of terrain, a lack of access to technology, and language and cultural barriers. He did so by building personal relationships, never missing an opportunity to forge a connection, patronizing the local bars, talking to anyone willing to listen, making friends, attending weddings, and even participating in exorcisms and ghost-dispelling rituals (a subject of great personal interest to him). In that respect Goullart is a literary ancestor to China-based authors such as Peter Hessler, Michael Meyer, and Rachel Dewoskin, whose writings also detail the challenges of being embedded in a local or professional community, hoping for acceptance while keenly aware that they ultimately never would be.

Goullart also used his rudimentary first aid training to dispense medicine from his home in Lijiang. But for every patient he helped, his outsider status also carried risk. He reflects that “if I gave them medicine and the men died, I would be considered a murderer and my life would not be worth a penny at the hands of an enraged family and clansmen.” His dark humor is, if not the best medicine, at least a remedy for diffusing other difficult situations:

I remember a well-to-do Tibetan who came to see me with well-defined symptoms of this confidential disease [syphillis]. He was horrified when I told him the truth.

‘No, no!’ he cried. ‘It is only a cold.’

‘How did you get it?’ I asked.

‘I caught it when riding a horse,’ he replied.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘it was the wrong kind of horse.’

Goullart’s access enabled him to write one of the best descriptions of life in Lijiang prior to 1949. It is not a perfect ethnography, and characterizations of Nakhi workers occasionally cross the line from paternalistic to kind-of-racist. A case in point:

The Nakhi were very independent and themselves never favoured the idea of a master and apprentice relationship. They had brains, though perhaps not very good ones by Western standards.

But more so than many foreign writers based in China in the 1930s and 1940s, Goullart made an effort to overcome biases, to respect people for who they were rather than who he wished them to be, and to humble himself when necessary in the service of learning more about his new home. His time in Lijiang ended in 1949, flying out on the same plane as Joseph Rock (to whom Goullart dedicated his book) after friends in Lijiang warned the two foreigners that they might become targets of the new regime. Goullart’s account of the early months of the Communist revolution in northwestern Yunnan is harrowing. Local religious leaders go into hiding; temples are destroyed, their paintings, books and icons burned. The new revolutionary committee ban traditional songs and dances. He goes on:

There were continual arrests, usually in the dead of night, decreed by the dread Executive Committee, and secret executions. It was reported that an old man at Boashi village was shot by a squad commanded by his own son.

no more (Jeremiah Jenne)

The extent to which the traditional culture of the non-Han nationalities in Yunnan was attacked as part of the revolution, continuing into the Mao years, should make contemporary travelers — such as those who flock to Lijiang over Spring Festival — skeptical of government pronouncements about how they have “preserved” Nakhi culture. A better description is “revived.” Less charitably, the Nakhi culture on display in Lijiang today presents selected elements from the past, recycled and repackaged for mass consumption, alongside the same snacks (such as “squid-on-a-stick”) and souvenirs as the “old streets” of Beijing, Xi’an, Dali or any other cultural destination.

Goullart also describes a locale in transition: his Lijiang is far from a static relic, but a society grappling with the challenges of early 20th century modernity. But like the Ship of Theseus, when does slow transition give way to something that has the form but not the substance of the past?

At the end of Forgotten Kingdom, Goullart writes:

Even during my youth spent in Moscow and Paris, I had been unaccountably attracted to Asia, her vast, little-explored mountains and her strange peoples and, especially, to mysterious Tibet … I had always dreamed of finding, and living in that beautiful place, shut off from the world by its great mountains, which years later James Hilton conceived in his novel Lost Horizon. His hero found his ‘Shangri La’ by accident. I found mine, by design and perseverance, in Likiang.

After being forced to flee his homeland as a young man, living the life of a wanderer, Goullart thought he had found his idyllic mountain valley to call home. Circumstances forced him to abandon it. If he could return, one wonders what he would think of it now. ∎

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.