The Qing dynasty (1644-1912) was something of a mixed bag. The 19th century is remembered as an era of humiliation, while the 18th century is considered a flourishing age, and has become the setting for many television costume dramas set in the courtyards and boudoirs of the imperial palace. But even during this prosperous “High Qing” era, cracks were starting to form that would eventually undermine both the dynasty and the imperial system as a whole.

Philip A. Kuhn’s Soulstealers is nominally about a mid-18th century Chinese witch hunt, in which local officials were put under immense pressure to investigate claims of sorcery, and the Qianlong Emperor deputized himself detective-in-chief. Yet underlying these investigations of magic and mayhem were the throne’s fears of sedition, which cast a dark shadow over an otherwise prosperous empire and shook the emperor’s confidence in the bureaucracy entrusted to govern it.

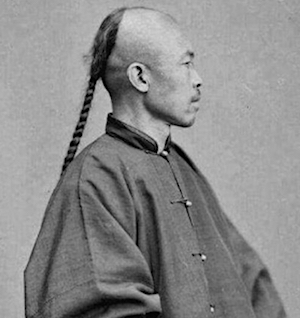

In 1768, rumors spread throughout regions south of the Yangtze River of sorcerers using various methods — most notably clipping the queue, the long braided hair of Chinese men — as a way to steal victims’ vital essences for nefarious purposes. Few local officials took the rumors seriously; the peasants were an ignorant lot, prone to believing all manner of superstition. But mass panic forced them to pass the news up the chain of command. When the emperor finally learned what was happening, he was shocked it had taken so long to reach his desk, and that officials were not doing more to combat what he saw as a grave crisis.

Kuhn argues that the ensuing campaign to nab sorcerers, which lasted several months beginning in the spring of 1768, revealed a hidden struggle between the emperor and his administration, illuminating political tensions that lurked below the ritualistic façade of imperial rule. The Qianlong Emperor was purportedly looking for sorcerers, but his real target was the bureaucracy. What did his officials know, when did they know it, and why were they keeping the throne out of the loop? And why was it that only the emperor cared that the main mechanism of the sorcerers’ magic was the cutting of the queue, a braid worn by Chinese men as a sign of submission to the ruling Manchu dynasty?

The adoption of this hairstyle had been enforced, on pain of death, since the early years of the Qing dynasty. Cutting off one’s own queue was a demonstration of rebellious intent. The emperor was sure there was a political message behind the sorcerers targeting this symbol of power and submission, which his officials had blithely ignored. In his darkest moments, he even wondered about a tacit collusion between these destabilizing local forces and an 18th-century “deep state” of entrenched bureaucrats, whose privilege blinded them to political crises and represented a threat.

The Qianlong Emperor was purportedly looking for sorcerers, but his real target was the bureaucracy.

At the time of its publication in 1990, reviewers of Soulstealers compared the Qianlong Emperor’s response to this sorcery scare with Mao Zedong’s political campaigns against Party elites in the 1950s and 1960s, but there are also easy comparisons to other times and places. From Vladimir Putin to Xi Jinping, the autocrat’s challenge remains the same: getting good information from bureaucrats who may not have their interest at heart.

The root of the problem was the Qing system of official accountability. An official could be punished for failing to report or prosecute a crime, but it was too often in their best interest to look the other way. Frustrated at the gravitational inertia of officialdom, the Qianlong Emperor wanted to whip his bureaucracy into shape. Unfortunately, as authoritarian rulers and cruel jockeys often find out, short-term gains made with the whip are usually lost over the long run.

When the reports of queue clipping and sorcery reached his desk, the emperor quickly took over the investigation. Where bureaucrats saw minor disturbances to local social order, the monarch saw an existential threat to his rule. Once the wheels of an imperial inquisition began to turn, only the emperor had the power to stop them rolling, and it was the Qing dynasty’s equivalent of today’s migrant workers and internal refugees who were crushed under their weight.

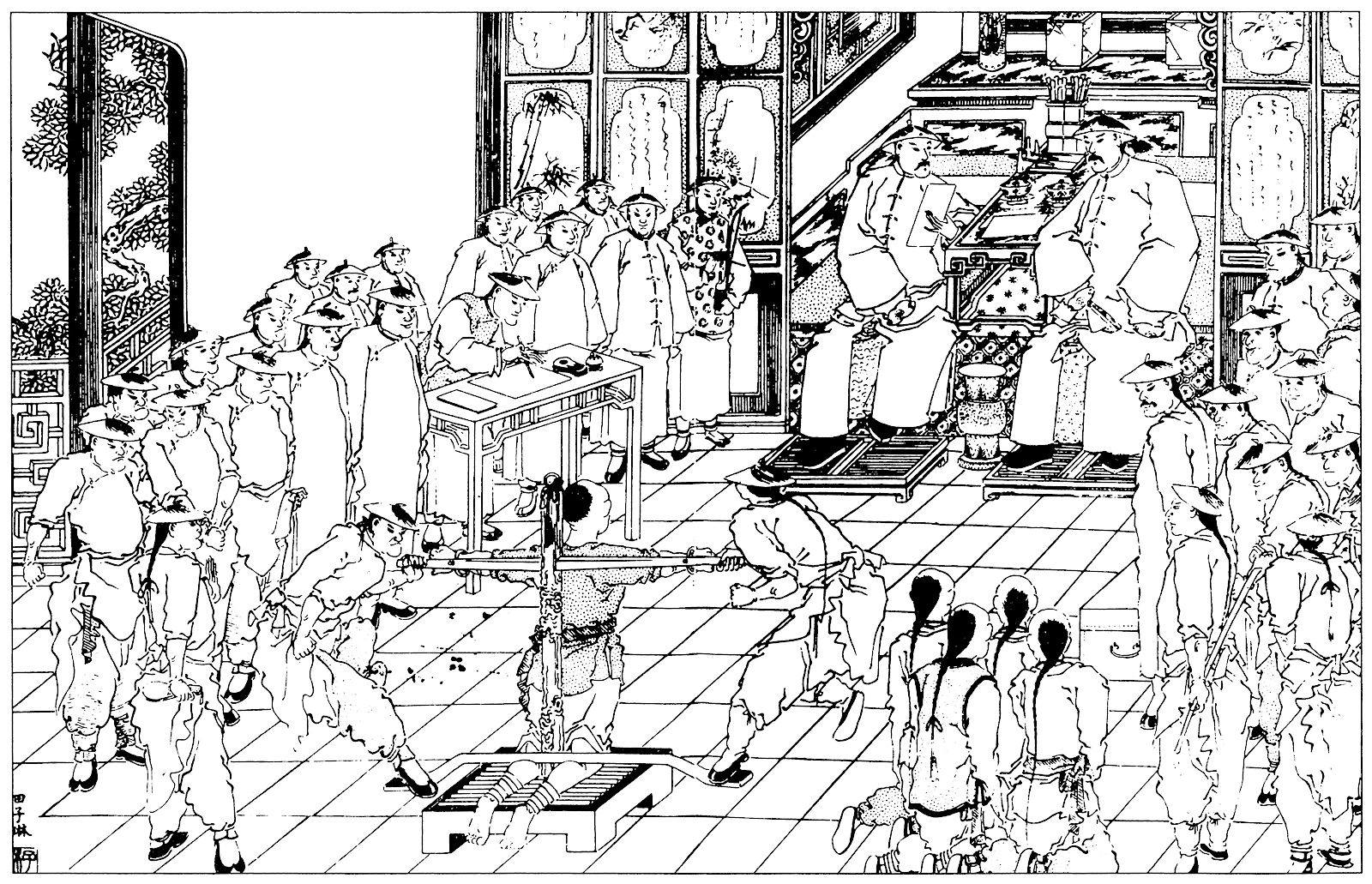

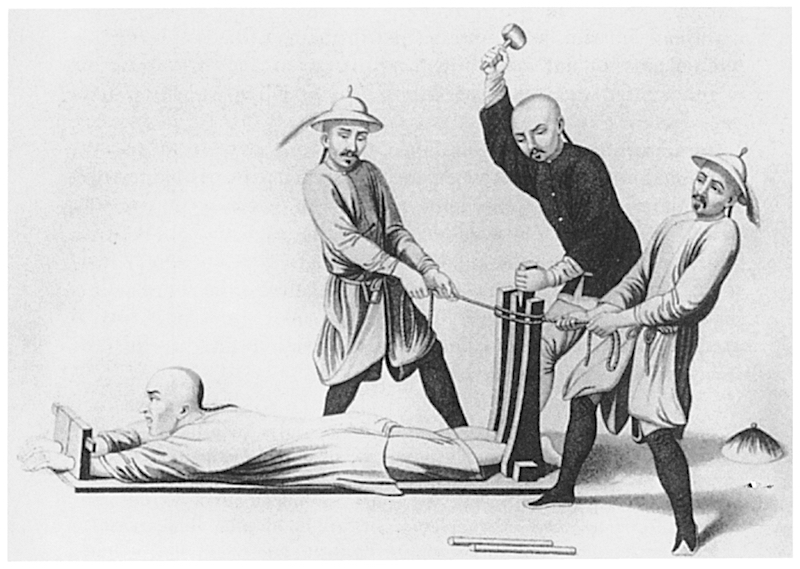

Even a prosperous age has an underclass. Economic prosperity does not mean fortune is spread equally, and in the Qing dynasty there was fierce competition at all levels of society. Historians estimate that the population of China may have doubled from 1650 to 1800, leading to surges in internal migration and displacement of those on the margins. More people taking to the roads meant more outsiders wandering into local communities, such as monks and itinerant beggars, who became easy targets for suspicion after the emperor put his officials into crisis mode. Dozens of people were arrested, interrogated under torture, and imprisoned.

While Kuhn’s book is an academic study, his research is compelling, poring over reams of official palace correspondence, court edicts, interrogation notes, and field reports. It’s the 18th-century equivalent of reading a vast trove of inter-office emails, complete with attachments (folded within the pages of official correspondence), snippy replies (the emperor was an impatient boss) and reminders not to hit reply-all (multiple government departments became enmeshed in chains of communication).

This kind of deep archival dive is the bread and butter of historians, and Kuhn was a master at using these resources. (It’s also worth mentioning Kuhn’s acknowledgment of Beatrice Bartlett, who passed away recently and whose guides to the Qing imperial archives have been required reading for generations of aspiring historians.) Yet Soulstealers does not shy away from the problems of archives more broadly. What do we do about forced confessions given under torture? Historians have long had to consider the quality of information obtained under such circumstances, and even the Qianlong Emperor himself questioned the truthfulness of testimony given while the prisoner’s ankles were being broken.

In the end — spoiler alert — none of the rumors of sorcery were proven to be true, most of the key witnesses proved unreliable, and the campaign fizzled out a few months after it began. Yet not before several of the accused were maimed or died as a result of their incarceration and interrogation. The Qianlong Emperor would rule for nearly 30 more years, and his era is remembered today as a golden age in Chinese history — but by the time of the emperor’s death in 1799, it was clear that internal corruption, mismanagement of imperial finances, and the kind of bureaucratic malaise that so enraged him had sapped the dynasty of its vitality. Moreover, the last years of the Qianlong Emperor’s time in power were beset by subversive groups such as the White Lotus Rebellion, which was far more destructive to dynastic legitimacy than a group of queue-clipping occultists.

Soulstealers is ultimately a commentary on the nature of power and governance. Kuhn demonstrates that the politics of fear is an enduring aspect of human societies, not confined to any one era or regime. By writing about the Qing dynasty, he invites readers to reflect on contemporary issues of authority and public manipulation. The Qianlong Emperor’s annotations on unofficial documents reveal his anxieties about subversion of his rule and a loss of imperial vigor, despite the Qing dynasty being at the zenith of its power. Even rulers who seem to have a firm grip on power, presiding over a prosperous economy and enjoying the fawning loyalty of their functionaries, have much to fear. Perhaps China’s past emperors still have something to teach the leaders of today. ∎

Homepage thumbnail: Convicts arriving at a county yamen in the lower Yangtze region, in cages and cangues. (Harvard University Press)

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.