A country’s history underpins everything that follows, as do our own personal histories. These are the stories we tell about ourselves — or that others tell about us. The last century of Chinese history alone has produced enough different accounts of events for a lifetime of reading. But history has always been dictated and disputed, divided by epoch and theme, into macro versus micro, public versus personal, and it is never singular. Which version is true depends on who you’re asking. It’s no surprise, then, that histories can sometimes read like fiction, whether about individual lives or political events. Fictional or poetic prisms can be a way to break free from established narratives, and maybe even to go looking for a little truth.

In this roundup of recent translated Chinese literature, we bring you five titles that explore different historical periods and personal narratives across the Sinophone world, from distinct perspectives and with varying approaches. A graphic novel tells the story of 20th-century Taiwan in images; a mystery novel unravels China in the 1960s; a fictionalized breast cancer memoir pushes the boundaries of the genre; a poetry anthology connects cultural roots across time and space; and a short story collection offers tales of resistance from 1970s Malaysia. These are the stories that make our histories.

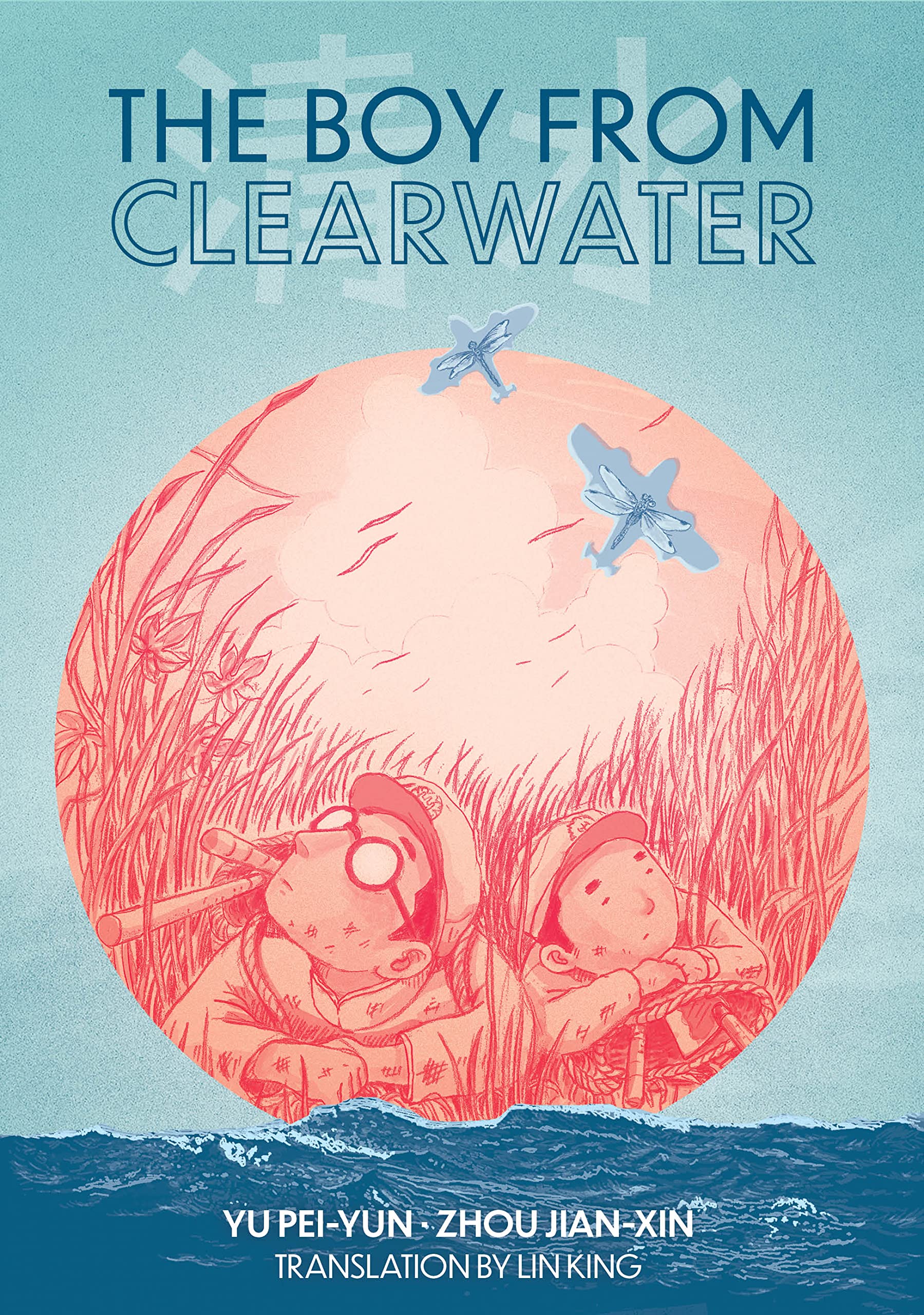

The Boy From Clearwater

Tshua Khun-lim enjoyed a peaceful childhood in the 1930s, growing up in the town of Kiyomizu on the western coast of Japanese-occupied Taiwan. At 15, he was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army to fight against the Republic of China. When he returned, Taiwan had a new ruling power, the Kuomintang, and a new official language, Mandarin. His town was renamed Chingshui (清水). The martial law and political repression of the “White Terror” struck the island, and Khun-Lim was sent to serve ten years on an island prison for his involvement with an “illegal” book club; he later became one of Taiwan’s foremost human rights activists. This graphic novel is his incredible story, depicted in comic-style drawings by award-winning illustrator Zhou Jian-Xin, which shift in style along with the seasons of Khun-lim’s life: from pastel pinks and soft, pencil-like sketches to blockier lines and heavier blacks. Author Yu Pei-Yun worked closely with her subject to write both volumes in this duology (the second recounts his life after his release from prison) before Khun-lim passed in 2023, and the translation from Hoklo Taiwanese, Mandarin Chinese and Japanese is a truly impressive feat by Lin King. Combined, this is a tale not only of incarceration, torture and oppression, but of solidarity, freedom and hope.

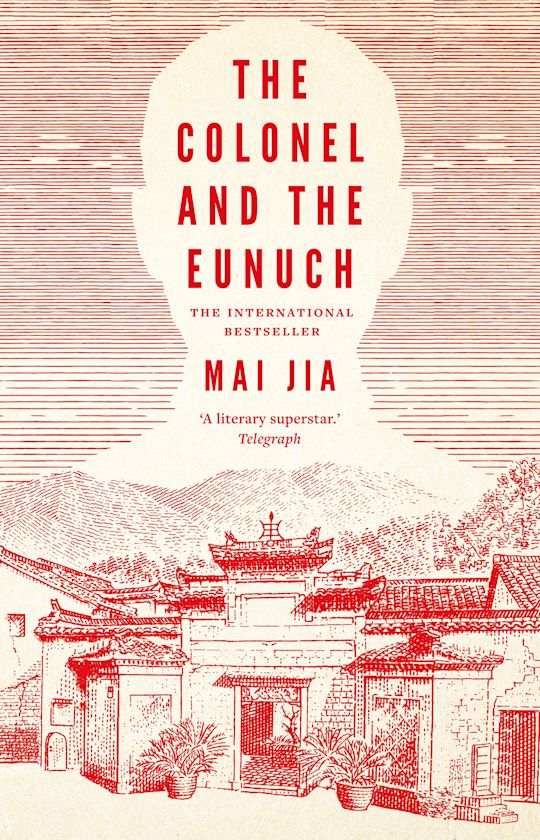

The Colonel and the Eunuch

A decade since the multi-million selling novel Decoded first came out in English (followed by a translation of his previous book The Message in 2020), Mai Jia has a new novel. This latest is a departure from those espionage thrillers, but (in Dylan Levi King’s romping translation) Mai’s signature intrigue and sense of humor remain. In a 1960s southern China village, a teenage boy tries to piece together the truth about his enigmatic middle-age neighbor, whose existence is surrounded by a swirl of rumor and myth. Nicknamed the Colonel, or the Eunuch, this neighbor is said to have fought on both Communist and Nationalist sides of the Sino-Japanese and Chinese Civil wars, while also living a life of debauchery despite his supposed lack of manhood. He is a figure who arouses reverence and scorn in equal measure. As the boy gathers stories across the book’s three parts, of desolate hardship and shocking violence and sex, the country turns on its head — marauding Red Guards spread their Cultural Revolution, and the narrator and Colonel are both sent into exile. If the boy learns anything, it is how to keep going when the world around you is upended.

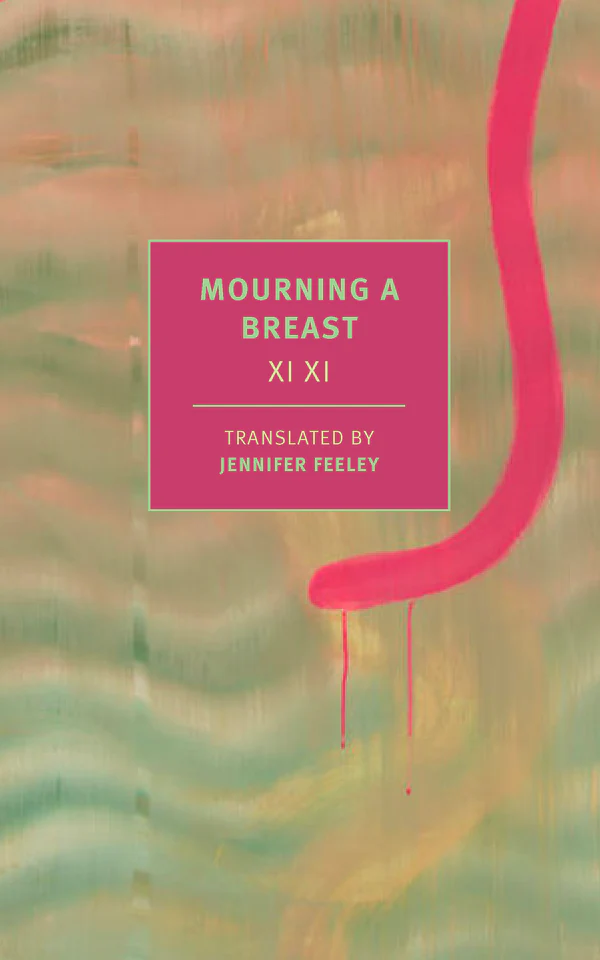

Mourning a Breast

“This is a book about breasts,” begins Xi Xi’s semi-fictional, semi-autobiographical account of her first months living with breast cancer (originally published in Chinese in 1992, three years after her diagnosis). But it is also a book about so much more: from her love of swimming and her discovery of a lump while in the pool changing room, to the history of Hong Kong shopping arcades and whether or not they sell bras with a single cup. Xi invites us into her mind through those early days of uncertainty — into the films and literature that helped her process the disease, as well as her theory on Taichi swordplay as physical therapy. In her own endearing way, she breaks with the conventional breast cancer memoir by giving readers some small sense of control over their experience, buoyed by positive thinking. Xi was the doyenne of experimental fiction in Hong Kong, winning both the Newman Prize (2019) and the Cikada Prize (2020) before her death from heart failure in 2022. Lovingly translated by Jennifer Feeley, Mourning a Breast suggests that she passed the intervening decades, between publication and the end of her life, as playfully and optimistically as ever.

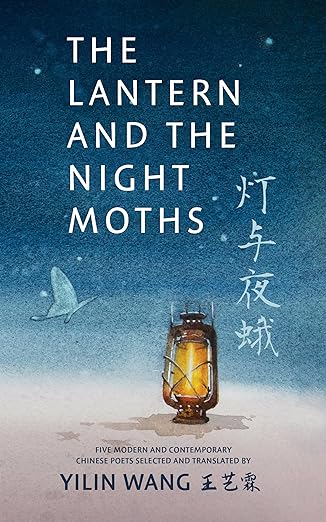

The Lantern and the Night Moths

The five poets whose work makes up this anthology were previously underrepresented in English translation. Translator Yilin Wang chose to shed light on Fei Ming, Qiu Jin, Dai Wangshu, Zhang Qiaohui and Xiao Xi because she considers them her “soulmates” (知音, a word that comes from a legend about a zither player who broke his instrument when he lost the person who best understood the sound of his music). The poems resonate with Wang, a Chinese-Canadian poet herself, in a way that makes her feel “seen,” as someone who translates her heritage language to reconnect with her cultural roots. Interrogations into identity and a sense of longing, or belonging, abound in lyrical verses in which butterflies flutter their wings, a lantern casts a faint light, and cicadas chirr. The pieces alone are resplendent in Wang’s translations (and in the original Chinese which features alongside them) but they are all the more colorful when refracted through Wang’s personal essays on the poets’ lives, and the craft and labor of poetry translation itself. Her discussions of the translation choices that she made or could have made are enlightening, and speak to the infinite possibilities of Chinese translation done with care and heart.

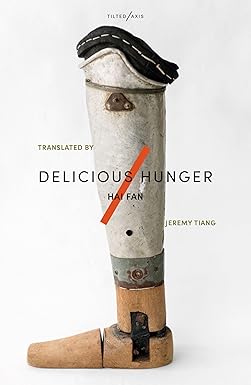

Delicious Hunger

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Malayan Communist Party engaged in guerrilla warfare to defend its supporters against persecution, and to fight both for basic rights and for what it envisioned as an ideal future. Writer Hai Fan entered the rainforest to fight for this cause in 1976, and Delicious Hunger is a collection of short stories inspired by the 13 years he spent there. Inevitably, the stories contain violence — gunfire exchanged with the Malaysian federal security forces, limbs lost in explosions, a wild boar mangled by traps. But they also show how jungle warfare continued into the comrades’ “downtime,” when food was scarce and had to be hunted in a landscape dotted by mines. We are reminded that everyday challenges do not vanish because of war: in one particularly touching moment, a young woman who struggles to share her feelings for a comrade becomes embarrassed about having her period. There is a sensory richness to the material descriptions (in Jeremy Tiang’s measured translation) of hunger and fear and damp. This is a reality full of quiet moments under siege: hushed conversations at a lookout; negotiations over workload; cooking the latest quarry. Through it, the stories center the quietest act of political resistance: living. ∎

Jack Hargreaves is a London-based translator from East Yorkshire. His published and forthcoming full-length works include Winter Pasture by Li Juan (2020) and Seeing by Chai Jing (2020), co-translated with Yan Yan; I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyan (2025); and A Man Under Water by Xiaoyu Lu (2026). He occasionally contributes to Paper Republic.