Reviewed:

• Thomas S. Mullaney, The Chinese Computer (MIT Press, 2024)

• Thomas S. Mullaney, The Chinese Typewriter (MIT Press, 2017)

Before Tom Selleck became the Hawaiian-shirted hero of Magnum PI, he starred in a made-for-TV movie titled The Chinese Typewriter (1979). Selleck plays Tom Boston, a tousled private detective who develops a trap to attract a fraudster hiding in South America. The plan is to sell him an investment idea “so big, so exotic, something that appeals to the imagination. Something that hasn’t been invented yet.” That idea is the Chinese typewriter. “You see in China,” Selleck’s partner explains, “there’s no such thing as a typewriter.’’

The notion of Chinese-ness as metaphoric of unfathomable complexity had already been established in the 1970s film lexicon by Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974). The famous last line — “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown” — is a friendly caution to Jack Nicholson’s bewildered PI that where he stood was beyond the understandable, or controllable. Yet compared to Polanski’s acclaimed neo-noir, The Chinese Typewriter was quickly forgotten after its release. As culturally insignificant as Selleck’s movie might be, its invention of the Chinese typewriter as an exotic impossibility is but one cultural manifestation of the long, charged debate over the relationship between modernity and the Chinese script.

It would be easy to assume from the titles of Thomas S. Mullaney’s The Chinese Typewriter (2017) and The Chinese Computer (2024) that these books are object histories of the kind that have become fashionable over the last 15 years or so, exploring how salt, cod, the pencil and so on have “changed the world.” But Mullaney, while seamlessly outlining the chronology of these two objects’ technological development, offers a far richer exploration of the linguistic, philosophical and political questions they pose. While Jing Tsu’s 2022 book Kingdom of Characters (a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize) has brought welcome popular attention to the story of Chinese script reform, Mullaney’s work offers a deeper dive, founded on scrupulous archival investigation into the infrastructural and conceptual reinvention of Chinese characters in the digital age.

Mullaney begins his epic tale in media res, during the 2008 Beijing Olympics, when the order of the parade of nations during the opening ceremony did not follow the conventions of the English alphabet. As American sports commentator Bob Costas observed, “There is no alphabet here.” Instead, teams entered according to a well-known (in China) organizational system based on the number — and, if necessary to discriminate, order — of strokes in the first character of their Chinese name. This was despite the fact that Chinese can also be organized via the Latin alphabet-based romanization system of Pinyin (拼音, literally “spelled sounds”) developed in China in the 1950s, which is widely used today alongside Chinese characters.

The International Olympic Committee had stipulated that the sequence of the parade follow “alphabetic order as it [functions] in the host country’s language.” But, Mullaney points out, this was another example of a “false universalism” which excluded the Chinese language:

Whether Morse code, braille, stenography, typewriting, Linotype, Monotype, punched-card memory, text encoding, dot matrix printing, word processing, ASCII, personal computing, optical character recognition, digital typography, or a host of other examples from the past two centuries, each of these systems was developed first with the Latin alphabet in mind.

The resulting divide was (with Mullaney’s emphasis) “one that pits all alphabets and syllabaries against the one major world script that is neither: character-based Chinese writing.”

It would be easy to conclude from this alphabetic dominance that, pragmatically, China should have adapted long ago to make its script compatible with Western technological modernity. Indeed, the idea that China should dispense with Chinese characters entirely has a long history. “First we must abolish Chinese characters,” wrote Qian Xuantong, a professor of literature at Peking University, in the 1918 essay “China’s Script Problem From Now On” (中国今后之文字问题), published in New Youth (新青年) magazine. “And if we wish to get rid of the average person’s childish, naïve and barbaric ways of thinking,” he continued, “the need to abolish characters becomes even greater.” Qian argued that reforming the linguistic system was the easiest way of abolishing Confucian and Taoist thinking, which he believed were ideological handbrakes on Chinese modernity.

Others, like the intellectuals Lu Xun and Chen Duxiu, were allies in this “anti-character chorus,” writes Mullaney, for whom “abolishing characters would constitute a foundational act of Chinese modernity, unmooring China from its immense and anchoring past.” Several early 20th-century Western thinkers, such as the classicist Eric Havelock and the sinologist Derk Bodde, also extended the Hegelian view that the Chinese writing system reinforced China’s supposed cultural and intellectual stagnation. Even Mao Zedong, both before and during his years leading the country, expressed support for replacing Chinese characters with a phonetic system, seeing it as a necessary step toward modernization and mass literacy.

Mullaney brands this criticism of Chinese characters as “easy iconoclasm” that is “incandescent, seductively quotable, yet ultimately naïve.” Despite these century-old debates, he points out, Chinese characters have not only survived today, but underpin China’s vibrant technological modernity. His work is an exploration not of whether Chinese characters should or could survive Western-centric modernity, but rather how they have survived — and prospered — in the face of technological challenges that at times seemed insurmountable. He writes:

Seductive though it may be, To be or not to be? was never the primary question of Chinese linguistic modernity. The question was: To be, but how?

The challenge was not only to reconcile a logographic script with alphabetic technologies such as the typewriter and computer, but to question assumptions that linked the Western alphabet with modern reason, democracy and science. In this context, Mullaney charts a strikingly different narrative of linguistic modernity — one grounded not in technological belatedness but in inventive adaptation.

The Chinese typewriter as an exotic impossibility is but one cultural manifestation of the long, charged debate over the relationship between modernity and the Chinese script.

The focus of Mullaney’s books is on “those who made possible China’s contemporary information environment,” whose work was “grindingly technical, dogged by intractable challenges, but ultimately of unparalleled success and significance.” The fundamental challenge that this diverse set faced was how to make Chinese script compatible with the established form of one, all-conquering machine that was built for the Latin alphabet — the Remington single-shift typewriter, which debuted under another name in 1873.

The restrictions inherent in this Western-built input system effectively defined the parameters of the experimentation in Chinese mechanization and digitization that would continue for the last 150 years. The Western typewriter was designed around the Latin alphabet’s 26 letters, which could be accommodated on a compact keyboard, especially after the introduction of the shift key for capital letters, doubling character capacity. In stark contrast, written Chinese requires thousands of unique characters — 3,000 to 4,000 for everyday literacy, and upwards of 40,000 for full scholarly or archival use. The basic mechanical model of a typewriter, which relies on a one-key-per-character or single-typebar system, was fundamentally unsuited to a language that could not be broken down into a small set of recombinable phonemes. The challenge, then, was how to build a typewriting machine that could store, organize and retrieve thousands of discrete characters without requiring an impossible number of keys.

Three prospective theoretical solutions to this challenge were explored during the 19th century, which Mullaney terms “puzzlings” of Chinese: “common usage, combinatorialism, and surrogacy.” The first approach, common usage, was to retain Chinese characters in their original form but to streamline the working lexicon (that is, identifying and standardizing a core set of essential characters) in order to reduce the number of keys that a Chinese typewriter would need to accommodate.

The second approach, combinatorialism, was to divide individual characters into their component parts, with the idea that they could then be reconstructed shape by shape. “To print the character ming (明 ‘brightness’),” the 19th-century Orientalist Jean-Pierre Guillaume Pauthier argued, “one could combine two smaller metal sorts [individual piecexs of cast metal type] to create a composite: one metal sort featuring the sun, ri (日), and one featuring the moon, yue (月).” In this antiquated view, Chinese characters could be “spelled” just like words in the Latin alphabet — a thesis that overlooked the enormous variation in size and position of each of the radicals that constitute a character.

The final solution, surrogacy, keeps the characters as they are, but uses a surrogate code to represent them. The most straightforward example of this comes from the Chinese telegraph code of 1871, which organized 6,800 common usage Chinese characters using the radical-stroke system, then assigned each a four-digit numerical code, meaning that at both ends telegraphers were dealing with numbers, not characters.

An American missionary named Devello Z. Sheffield, who arrived in China in 1869, is the first in a long parade of inventors who attempted to turn theory into practice and actually build a Chinese typewriter. Sheffield, who was based in the (then separate) city of Tongzhou, just east of Beijing, curated the characters he needed, trimming the 40,000 plus of the 1716 Kangxi dictionary to a more manageable 4,662 — divided into 726 “very common” characters, 1,386 “common characters,” and various less common characters (including new Biblical vocabulary, such as the translation for Jesus, 耶穌). Sheffield’s typewriter, which came out in 1888, resembled a small round table, with 30 concentric circles of characters designed to be easily reachable by a sedentary operator. It was never built or sold, but its reduction of the Chinese lexicon into essential elements would be profoundly influential.

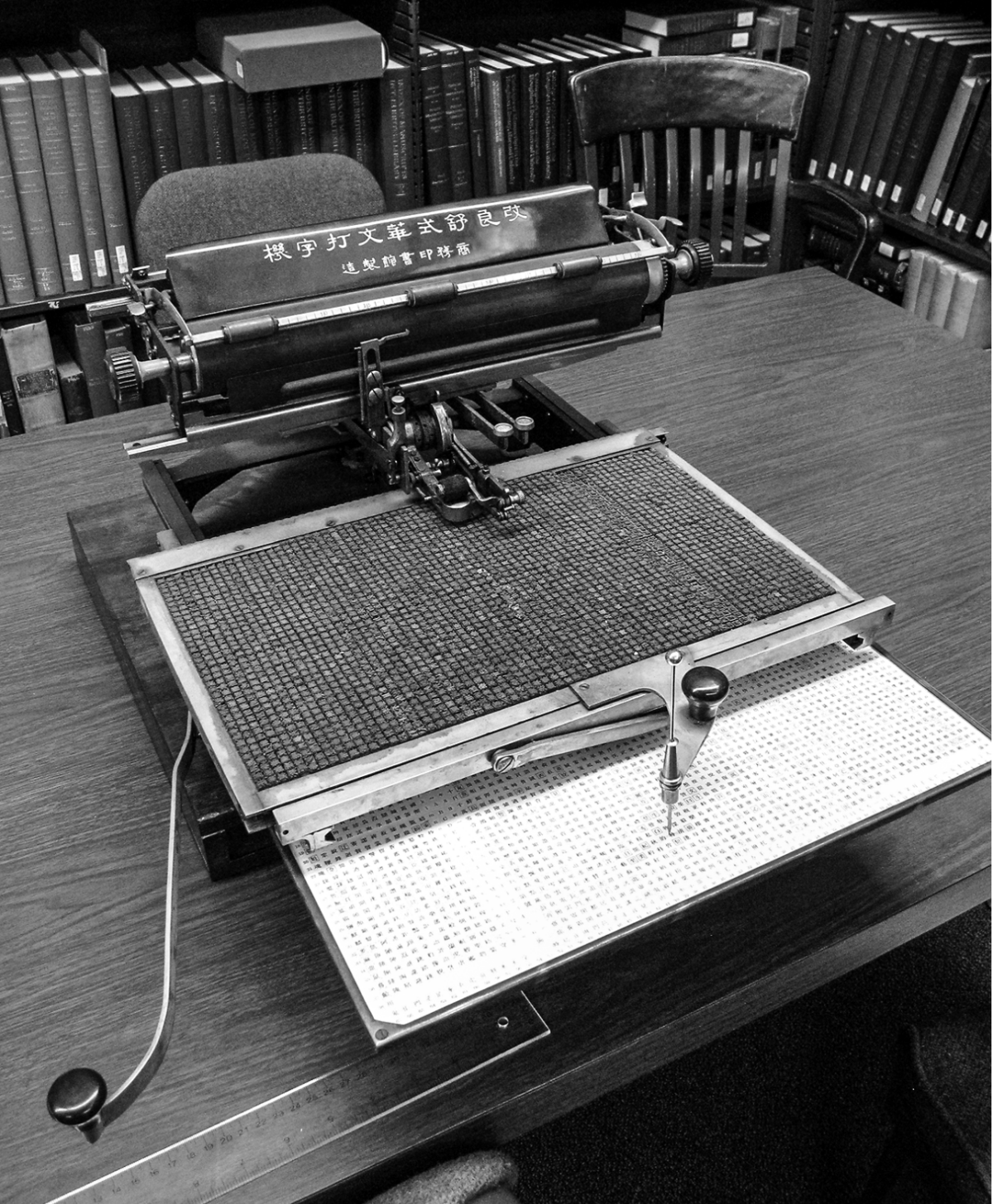

Mullaney goes on to trace in remarkable detail the mechanical refinement of these typewriters — and the many imaginative, awkward and oversized designs that emerged in the attempt to solve the Chinese script problem. Some designs were based on rotating drums; others on tray beds with thousands of free-floating metal sorts; some even imagined characters stored on internal gears. One of the earliest prototypes to reach functional completion was built by a Chinese mechanical engineer studying in the U.S., Zhou Houkun. His 1914 machine featured a cylindrical component around which approximately 3,000 Chinese character slugs were arranged according to the Kangxi radical-stroke system. Instead of a keyboard, there was a printed grid of characters on a rectangular bed at the front of the machine. The operator would move a metal rod over the desired character on this grid; the opposite end of the rod would then guide the corresponding character on the cylinder into printing position.

Around the same time, another young Chinese inventor, Qi Xuan, was racing to build a typewriter of his own, with a cylinder of 4,200 common usage characters, but also a set of 1,327 “pieces of Chinese characters” that could be used to “spell” less frequent characters by assembling their radicals into the required position before pulling a lever to imprint it. Though neither Zhou or Qi’s typewriters were commercially produced, their prototypical endeavors were fundamental in the development of the Shu-style typewriter, which became China’s first commercially produced typewriter in the late 1920s.

As Mullaney shows, the story of the Chinese typewriter was political as well as technical. Japanese typewriters (with systems for syllabic hiragana and katakana as well as kanji characters) became widespread in China in the 1930s, as Japan’s imperial expansion intensified. “Chinese inventors and manufacturers watched as the Chinese typewriter,” writes Mullaney, “steadily became the purview of Japanese multinationals.” In the aftermath of the Communist victory of 1949, China took control of the Japanese Typewriter Company and proudly renamed it the “Red Star Typewriter Company” — a symbolic act of nationalist reappropriation. This culminated in the launch of the Double Pigeon (双鸽) typewriter in 1964, based on a previous Japanese model, that became the defining Chinese typewriter of the socialist era.

In terms of Mullaney’s overall argument, perhaps the most significant individual in this first volume is the Chinese writer, translator and inventor Lin Yutang. In the 1930s, Lin designed the MingKwai typewriter, which aimed to simplify Chinese text input. The MingKwai operated differently from other typewriters. It did not rely on typing characters directly from an input; instead, a system of metal bars and rotating gears inside the machine retrieved characters based on the operator’s input. The machine allowed the user to select characters from a small list displayed in a viewfinder, requiring only a few keystrokes to find and select a character, before typing it.

Despite Lin Yutang’s efforts, the MingKwai typewriter was also never mass-produced. It drew praise from intellectuals and interest from companies, including Remington, but financial difficulties and political turmoil in China (the Chinese Civil War and subsequent Communist victory) hampered its development. Though MingKwai ultimately failed as a commercial product, it represented a significant shift in Chinese information technology. In particular, in its merging of character search with writing, it anticipated a range of modern input methods, where users provide criteria for retrieving characters rather than directly typing them — a method that would come to underpin the hard-won success of the Chinese computer that followed.

In antiquated views, Chinese characters could be “spelled” just like words in the Latin alphabet.

In 2016, the year before the publication of The Chinese Typewriter, Mullaney published an article in Foreign Policy titled “Chinese Is Not a Backward Language,” arguing that those who suggested Chinese was incompatible with modernity were guilty of “Orientalism 2.0.” A week later, David Moser (author of A Billion Voices, another history of the modern Chinese language) responded that the piece constructed a straw-man argument. Moser argued that the fact that computer scientists overcame the challenges of digitizing Chinese script did not mean that prior observations of those challenges were invalid, inaccurate or orientalist.

“The main thing wrong with Mullaney’s utopian reasoning,” Moser wrote, “is that he focuses exclusively on the problem of digitizing Chinese characters for processing and manipulation in cyberspace, ignoring a host of other deep-seated problems that still persist.” Amongst other issues, Moser identified the problem of educated adults forgetting characters as exemplifying some of the difficulties of the Chinese script. This “character amnesia” or “dysgraphia” (提笔忘字) problem in Chinese, he continued, “has been a problem for centuries, and made only worse now with the advent of the Pinyin input method and voice messaging options on digital devices.”

Mullaney’s second volume, The Chinese Computer, begins by posing a direct counter-factual to this argument, asking of China’s 900 million internet users: “If China’s most connected, tech-savviest individuals are ‘incapable of writing’ (a baseline definition of dysgraphia), who is doing all this Chinese writing?” He tells the story of a young man named Huang Zhengyu who, in 2013, won the National Chinese Characters Typing Competition, writing an average of 221.9 characters per minute as he transcribed Hu Jintao’s 2011 speech “Hold High the Great Banner of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” The digital method of writing that enabled Huang to produce Chinese characters at such remarkable speed, Mullaney argues, has enabled a new form of literacy, rendering debates over character amnesia effectively irrelevant. Mullaney coins the neologism “hypography” to refer to this system, merging the Greek hypo (under, lesser) and graphia (to write).

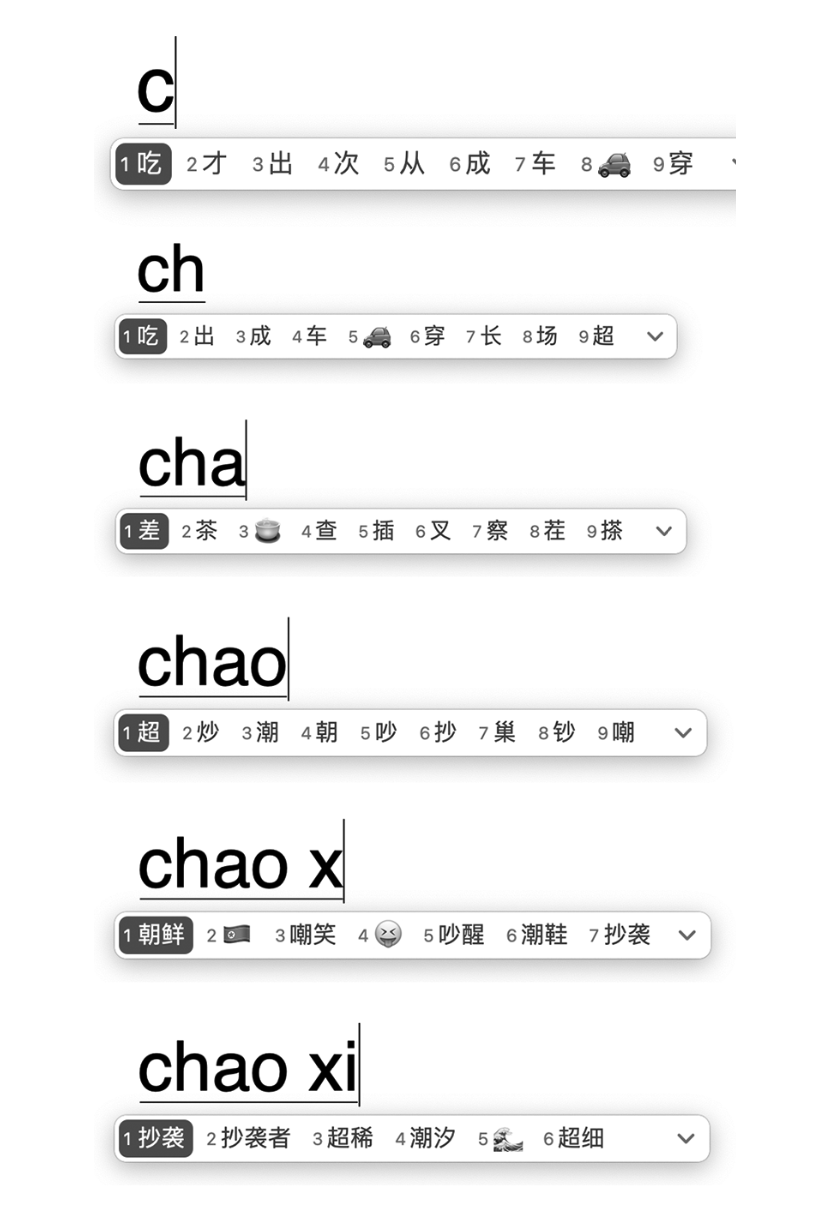

Readers over 35 might be familiar with T9 input on mobile phones from the 1990s, when, in order to write text in the absence of a QWERTY keyboard, one would repeatedly press the number keys in order to type predictive alphabetic text (for example, 4-3-5-5-6 would allow you to type ‘Hello’). Chinese text entry relies on similar software, often built into operating systems, called Input Method Editors (IMEs). For example, when I wanted to type the Chinese characters for “dysgraphia” I switched my input method to “Pinyin – Simplified” and typed the letters ti. As soon as I typed the letter t, my computer offered me eight Chinese characters (and one emoji) as it tried to guess which character I might want. These selections changed again when I pressed the i key; the character I wanted was then first in the list (though if I had regularly been writing a different ti character, the order of options might have been different).

In order for this system to work, it is worth noting that I need to know both the Pinyin “spelling” of the character, and what the Chinese character looks like (there are plentiful possibilities to get the choice wrong when faced with similar looking characters). Mullaney’s argument is that despite these additional layers of mediation, the speeds one can achieve via Chinese input methods can match or even surpass those of “what you type is what you get” QWERTY keyboards. Indeed, he goes further to claim that this signals the beginning of a “new era in the history of writing”: not the age of orthography (conventional writing) but the early days of the “age of hypography.”

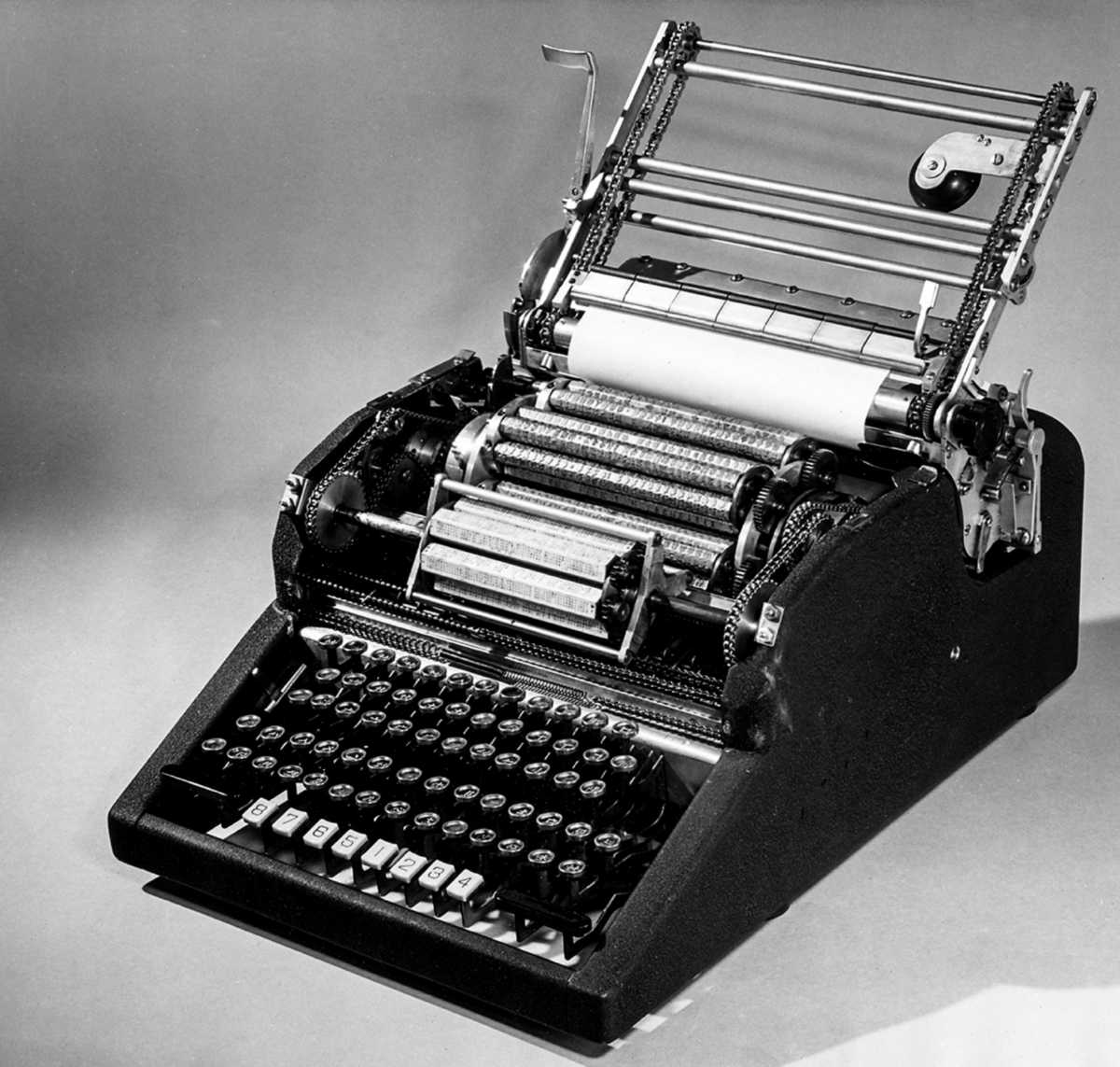

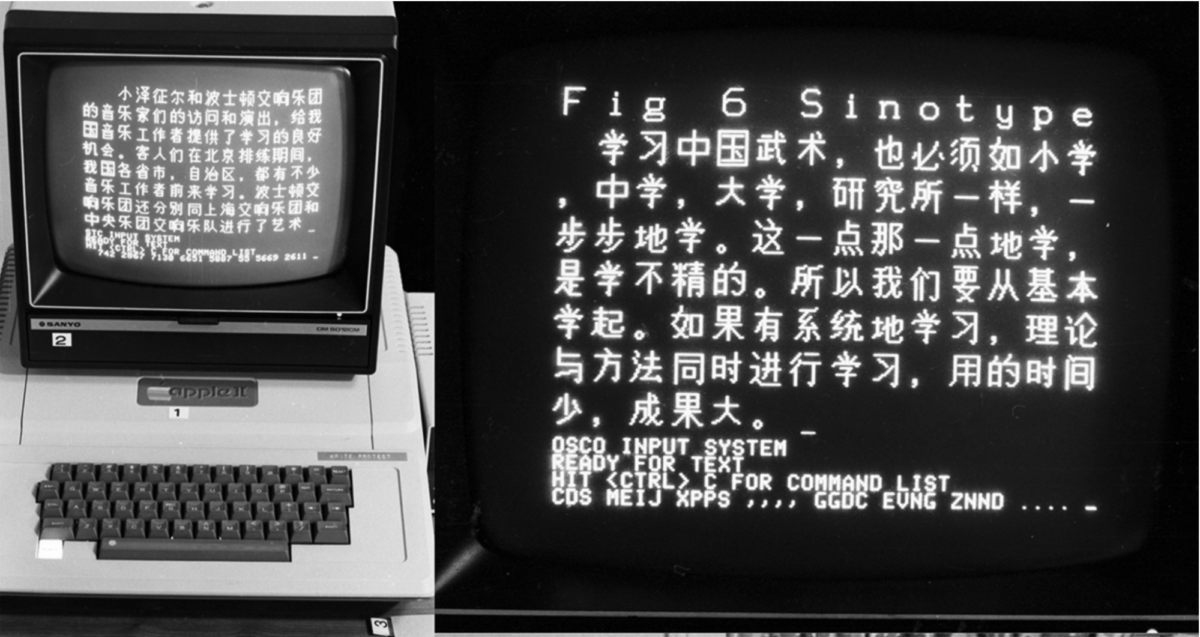

There were plenty of technological hurdles to jump before the dawn of this new digital era for the Chinese script. In early chapters, Mullaney narrates the competition of a range of systems for electronic Chinese character input, many of which dispensed entirely with QWERTY in favor of other keyboard arrangements by the 1930s and 40s. Chinese engineer Chung-Chin Kao, working with IBM in 1947, developed one of the earliest prototypes of an electric Chinese typewriter, which required the memorization of four-digit codes corresponding to 6000 characters, to be entered by a professional typist. This was followed by a wave of innovation from the 1950s to 1980s, by Chinese engineers both in the diaspora and in China, from digital pointer-systems and numeric panels to custom key arrays.

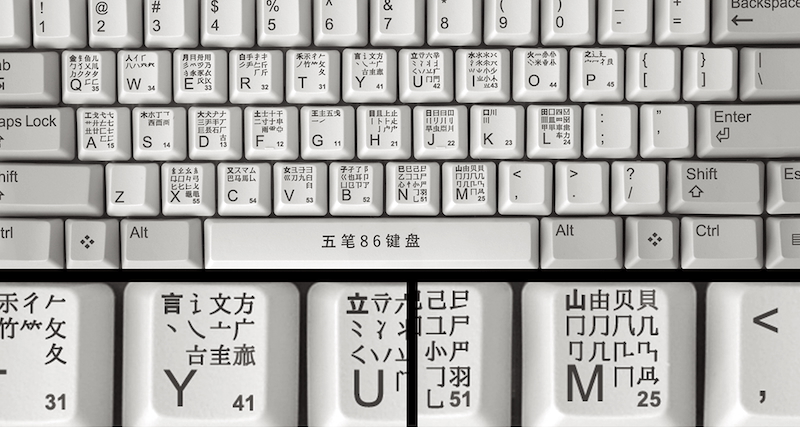

By the early 1980s, this hardware plurality effectively disappeared as QWERTY keyboards established their dominance. However, the diversity of keyboard input methods for Chinese meant a single character such as 电 (electricity) could be retrieved through a bewildering range of input sequences on your QWERTY keyboard: by typing “DDDD” when using OSCO, a visual shape-based system; “KZVV” using Zheng code, which mapped character structure to fixed codes; “NY” in the Tiaji system, a simplified radical-shape input; and “JNV” with Wubi, a stroke-based method that broke characters into component parts mapped to specific keys. While the specifics can be dizzying, the broader arc becomes clear: a chaotic field of competing techniques slowly gave way to technological convergence, anchored in the shared infrastructure of QWERTY and the rise of adaptable Input Method Editors.

The challenges of digitizing Chinese extended beyond questions of input, however. The hardware and software of computers in the 1980s simply couldn’t cope with Chinese characters. Monitors couldn’t display them; storage systems couldn’t store them; printers couldn’t print them. A useful example of this is found in the encoding system ASCII, the American Standard Code for Information Interchange. Developed in the 1960s as a default character set for Western computing devices (now replaced by Unicode), ASCII used seven 0s and 1s to represent each character, from 0000000 to 1111111 — a seven-bit system (a bit is a binary digit) that allowed for 128 possible characters to be stored. While that is just about okay for the Latin alphabet (it would later be expanded to eight bits per character, allowing 256 options) it was woefully inadequate for storing thousands of Chinese characters. This led to a burgeoning community of “modders” — engineers who would modify Western computer systems to cope with Chinese characters, effectively retrofitting machines never designed to handle such a vast character set.

As Pinyin began to be more widely taught in schools during the 1980s, it also triumphed as the dominant mode of digital Chinese character input — though, as Mullaney points out, other structure-based systems such as Wubi remain quicker, once the hurdle of learning them is overcome. The rise of Pinyin (which maps onto the pronunciation of standard Mandarin) was also a challenge for those who spoke Cantonese, Shanghainese or one of China’s many other languages or dialects. “Pinyin input helps turn Chinese computing into another tool of state-led Chinese nationalism,” Mullaney writes in the book’s final chapter, arguing that it reinforces a standardized, state-sanctioned vision of language that aligns with the PRC’s broader nationalistic goals. Questions of fairness aside, it was Pinyin via QWERTY keyboards that ultimately won the race to type in Chinese.

The challenges of digitizing Chinese extended beyond questions of input. The hardware and software of computers in the 1980s simply couldn’t cope with Chinese characters.

There are books that you wish you had written, and others you are glad you did not have to write. Mullaney’s duology — best thought of as one book published in separate volumes — falls into the latter category. It is scrupulous in its research; detailed to the point of being overwhelming in its technical explorations; and thoughtful in its interrogation of technology’s cultural implications. It also feels necessary. This history deserves to be known, and I am grateful that someone else has done the years of hard research necessary to write what feels like the endeavor of a lifetime.

Mullaney finishes with a reflection on the global rise of writing through mediated input methods — which we use every day on our smartphones as they autocomplete our words and sentences. In the digital age, writing is no longer a direct act of inscription: it’s a process of retrieval, selection and collaboration with machines, rendered even more interactive with the rise of AI and Large Language Models, which take these acts of prediction even further.

Just as he opened his first volume with the 2008 Beijing Olympics’ Parade of Nations, drawing attention to Western assumptions of alphabetic universality, Mullaney ends his second volume by arguing that the technological innovations of Chinese computer scientists “saved” the Western-designed computer from its foundational limitations, and have redefined the very act of writing. It is an argument, however, that pushes the book unhelpfully into the realm of the polemic. This summation is emblematic of the book’s laudable ambition to recenter non-Western agency in the history of computing. But it risks mirroring the cultural triumphalism it seeks to critique, and feels, at least to this reader, an unnecessary rhetorical flourish.

The strength of both books lies not in sweeping pronouncements but in the detailed reconstructions of how Chinese scientists, engineers and coders overcame the technical and conceptual constraints of alphabet-centric machines — first with the typewriter and then the computer — and reshaped those technologies to meet the needs of the Chinese script. Those stories speak volumes on their own. ∎

Header: Grace Tong demonstrates the IBM Electric Chinese typewriter. (Mergenthaler Linotype Company Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institute)

Jonathan Chatwin is a writer and teacher focused on China. He is the author of Long Peace Street (2019), tracing the history of a single street in Beijing, and The Southern Tour (2024), an account of Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 tour of southern China to boost the nation’s private economy.