Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

The roaring twenties was a time when the world contracted. Wireless radio and phonograph records ensured the same jazz soundtrack was heard from Chicago to Shanghai. New magazines such as Reader’s Digest and Time brought stories from remote shores to parlor coffee tables. And the German guidebook publisher Baedeker was doing such a roaring trade that the verb “to Baedeker” became synonymous with “to travel.”

The interwar period was also a golden era for travel writing about China. Travelogues such as Somerset Maugham’s On A Chinese Screen (1922) and Peter Fleming’s One’s Company (1934) bookended the many classics penned during the era. East-bound travelers likely arrived with Carl Crow’s The Travelers’ Handbook for China (1913) in tow. The Japanese invasion of China in 1937 ended that era, and China would not open again for foreign travelers until the 1970s.

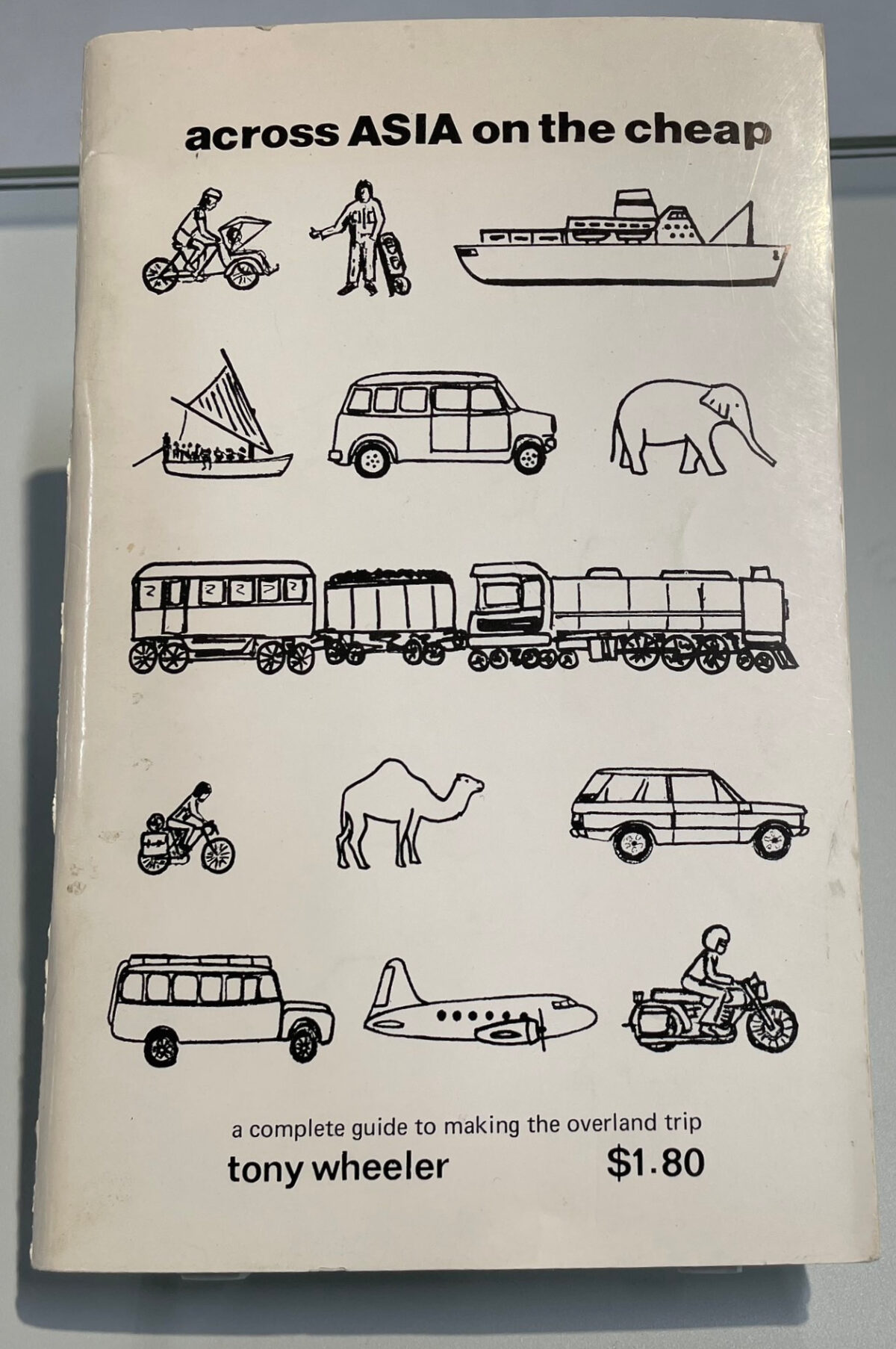

Out of the turmoil of World War II, a new passage was forged across Asia, the “hippie-trail” along which beatniks sought to “turn on, tune in and drop out” in exotic locales from Kabul to Kathmandu. It was along that trail that the look and scope of travel guidebooks would be transformed. In 1972, Tony and Maureen Wheeler traveled overland from London to Sydney, documenting their journey in Across Asia on the Cheap (1973), which at just 94 pages was the first edition of Lonely Planet, a guidebook series that has since printed over 150 million copies covering 288 destinations.

As individual travel took off, guidebook publishers mushroomed. Hans Hoefer brought us the highly visual Insight Guides series in 1970; Moon Travel Guides was founded in 1973, advocating “independent, active, and conscious travel”; Mark Ellingham began Rough Guides in 1982 with a guide to Greece; while the eponymous guides of Arthur Frommer and Eugene Fodor maintained respectable positions in the thriving travel book market. The ascent of the guidebook coincided with a renaissance in travel literature, as writers such as Paul Theroux, Colin Thubron and Bruce Chatwin injected new life into the genre. All would eventually visit and write about China, which, due to the Cold War, had been circumvented on the hippie trail of the 1970s.

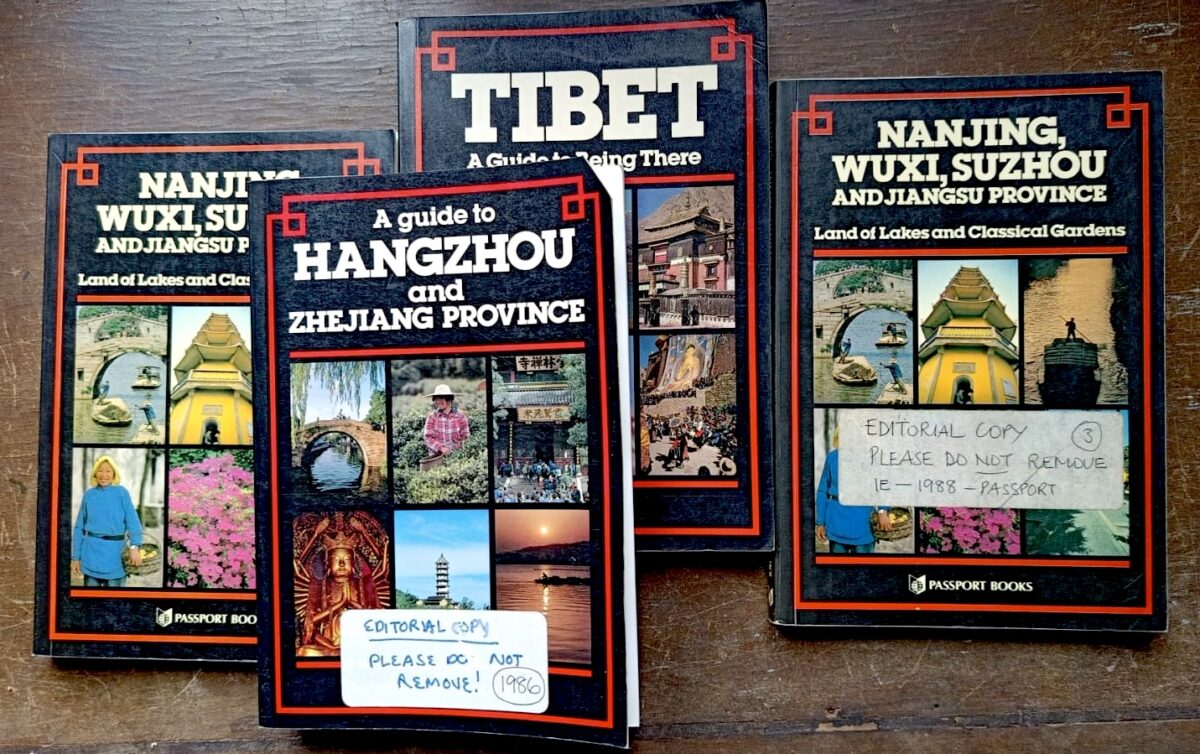

In 1978, Magnus Bartlett, a British photographer living in Hong Kong, visited “sleepy” Shenzhen as part of a group tour into China, newly open to foreign travelers after the death of Mao in 1976. “I was fascinated with this new, and in many ways, untouched world,” Magnus Bartlett told me by telephone from Lamma Island, Hong Kong. “It was antique, somehow pristine.” He promptly founded the China Guides Series, sold in the U.S. under the Passport imprint, which eventually became Odyssey Guides. “We published our Peking guide in 1979,” Bartlett recalls, “and went on to produce guides to Hangzhou, Nanjing and Tibet. All those early books sold well owing to there being no competition.”

As the bamboo curtain inched open, competition arrived. Lonely Planet published its first China guide in 1984, China – A Travel Survival Kit, adorned with a photograph of a peasant in a blue Mao jacket harvesting rice. By 2002, the cover of the eighth edition of Lonely Planet China featured a Peking opera singer seemingly serenading a new prosperity after the country’s entry to the WTO in 2001. The decade that followed, peaking at the Beijing Summer Olympics of 2008, was a time of unprecedented social and economic change that China-watchers have called the roaring aughts. As in the 1920s, books about China, including Peter Hessler’s River Town (2001), once again inspired suburban kids to pack their bags and land an English teaching gig in a little-known corner of China.

Lonely Planet published its first China guide in 1984, adorned with a photograph of a peasant in a blue Mao jacket harvesting rice.

In 2005, when I bought that eighth edition of Lonely Planet China in Hong Kong, I was about to head across the border into the mainland to begin an English teaching job in my very own river town: the small southern city of Huizhou, northeast of Shenzhen in the Pearl River Delta. Though historic and scenic, Huizhou didn’t even feature in the hefty 900-page guide (still too short to cover such a large country). The province of Guangdong, which Huizhou was located in, was also given short change, portrayed as a polluted, vice-ridden province best bused-through en route to Yangshou, the “backpacker’s laidback mecca of gorgeous scenery” located in neighboring Guangxi province.

Notwithstanding its shortcomings, my Lonely Planet accompanied me everywhere, from Xiamen to Xi’an. Its pages became ever more heavily-thumbed when I began a new trip, or envisioned one. I also imagined the day I might join the ranks of the authors listed inside. When I became the Shenzhen Editor of that’s PRD (Pearl River Delta, later that’s GBA for Greater Bay Area) magazine, the talk of the time was what the “digital revolution” implied for print-based publications. The rise of online travel content, including blogs and listicals, was rattling the industry. The release of the first iPhone in 2007 intensified the trend. Guidebooks sales plunged 40% between 2005 and 2012, due the rise of digital alternatives, a trend exacerbated by the financial crisis of 2008. Yet we never struggled for advertising revenue at our print magazine. Everyone wanted to sip from the Chinese cup, travel publishers included.

This led to a steady stream of writing assignments, including a contract to update the eighth edition of The Rough Guide to China in 2016. The eight writers working on the project were allocated regions, and I was given seven provinces south of the Yangtze River (some serious mileage considering that each province was the size of a medium-sized European country). China’s national transport infrastructure — its railways, expressways and airports — were being radically upgraded, which mandated some heavy rewriting of the “Getting There and Away” sections.

I began my trip in Beijing, rolling aboard a sleeper train through Guangzhou and onwards to Zhanjiang, a city on China’s far south coast. Here, the train cars were uncoupled one by one and shunted onto a specially designed ferry before sailing nine miles south to Haikou on the island of Hainan, where it was reassembled and continued its journey. I spent a few days laid up in the beach resort town of Sanya, after dodgy bowl of noodles struck me down, then bused across Hainan’s interior to the gate of the Wuzhishan Nature Reserve, where a security guard told me I wouldn’t be allowed in as an American hiker had got lost there a few months ago. These obstacles were par per course for guidebook writing but the rewards were greater than the compensation, with work taking me from the Buddhist grottoes of Luoyang and Dunhuang to the tea fields of upland Fujian and Hunan.

The greatest challenge of updating a China guidebook was just how fast the country was changing. Shenzhen, for example, had emerged as a dynamic innovation hub (Lonely Planet included it on its “best cities” list in 2019). Yet while journalists still traded in the “fishing village turned megacity” cliché, its depiction in the last edition of Rough Guides was still that of a seedy-border town. My predecessor wrote:

“Some Westerners may be familiar with Shenzhen as the global center of iPod production. This doesn’t necessarily mean there’s much of interest to the casual visitor.”

Readers were warned of “an atmosphere compounded by pushy touts, beggars and pickpockets.” Listed top among Shenzhen’s sites were two old public parks and a skyscraper erected in the 1990s, with no mention of the “hypermodern architecture, innovative environmental practices and a slew of new design openings” that Lonely Planet would soon be waxing lyrical about.

Insensitive tourist development was also a frustration in those boom years. Some atmospheric villages and historic sites had fallen victim to the whims of over enthusiastic tourist bureaus, who took their cues from Disneyland. Sometimes places, including Beijing’s historic alleyways and the evocative villages of Guangdong, disappeared altogether as the country developed with an unsentimental ferocity. Yet the geographic diversity and rich cultural landscape of China usually compensated for any misguided official designs.

In June 2017, a handsome new edition of The Rough Guide to China appeared in bookstores, with an inviting picture of a door opening onto the Temple of Heaven on the cover and my name listed at the back of the book. It felt like we were finally capturing the full scope of China for prospective travelers, far from the fumbling in the dark of the 1970s travel writers. That edition is, to date, the last guidebook covering all of China that Rough Guides have published.

The greatest challenge of updating a China guidebook was just how fast the country was changing.

There was nothing roaring about the early 2020s for those working in travel publishing. Host of the Travel Writing World podcast, Jeremy Bassetti, managed to hum some positive notes about how “travel book authors saw a spike in their sales” from “vicarious or armchair travelers.” Yet while the Therouxs and Thubrons of this world might have enjoyed a few extra bucks in their royalty checks, for those of us lower down the food chain, the outlook was summed-up by travel writer Jason Wilson, who described the pandemic as “the extinction event.”

He was not overstating. Print magazines and guidebooks were already struggling as social media influencers and nifty travel apps steered travelers’ attention to their phones. The Covid pandemic was a death knell for prominent print publications including Sunday Times Travel Magazine and Lonely Planet Magazine. In China’s case, the country closed in March 2020, and anyone who was able to travel there was subjected to a mandatory 14-day quarantine. The new editions of The Rough Guide to China and Insight Guides China that I’d already begun researching were mothballed. Sarah Clark, head of publishing at APA Publications, the company that owns both Rough Guides and Insight Guides, later told me: “We basically looked at everything that was on our list and if there was any way we could stop it, we stopped it.” The response was understandable given that, as Clark put it, “We lost 95% of our sales overnight.”

China also suffered a major image problem in the West after the first Trump administration locked horns with Zhongnanhai. China had become far more oppressive since Xi Jinping ascended to power in 2012, and as Washington’s stance hardened, America was met with reciprocal intolerance in China. Foreign journalists were ejected and international cultural events were curtailed, while the Covid pandemic accelerated an exodus of expatriates.

For one who believes in Mark Twain’s famous assertion that “travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and narrowmindedness,” I had come to see the work of the travel scribe in China as a countermeasure to political stratification, a rebuff to hardening perspectives, and a flashlight illuminating the wonders that persisted beyond the cold binaries of great-power competition. But such lofty goals felt like fantasy when confined to the sofa.

I was on assignment in Malaysia when the world locked down, and was stuck outside of China. After the Omicron wave in early 2022, Southeast Asia reopened to international travel and guidebook contracts picked up as publishers scrambled to update their catalogues. The post-pandemic travel publishing boom took me from the ancient heart of Hanoi to the surf paradise of Lombok. When China cautiously reopened in 2023, much noise was made in the press about business lost to regional competitors such as Singapore or South Korea. But tourists, too, had booked vacations elsewhere. The numbers tell the story: China recorded 13.8 million visitors in 2023, compared to 31.9 million in 2019.

At the start of 2025, according to the UN World Tourism Organization, international travel overall has surpassed 99% of 2019 levels, and is on track to exceed pre-pandemic levels. But inbound travel hasn’t recovered in any meaningful sense in China. As of 2024, foreigners were entering China at barely 30% of the rate they were in 2019. Even the expats are leaving: a report quoted in the South China Morning Post found a 40% drop in foreigners living in Beijing over a decade, and a 64% decrease of those living in Shanghai between 2018 and 2023.

Efforts to woo back international travelers with visa-free travel policies might improve the situation. Passport holders from a whopping 74 countries can now enjoy 30 days visa-free (though the U.S. and U.K. remain notable exceptions). But anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise; having just travelled from Yunnan to Beijing, foreigners remain notable by their absence. In particular, Americans are keeping away, with visitors from the U.S. down two thirds on pre-pandemic levels. According to The Economist, as of October 2024 monthly seating capacity for flights between America and China had only returned to 28% of what it was in 2019.

Everyone I talked to in China who works in tourism sings the same song about having to focus on the domestic market. Notwithstanding economic woes wrought by the aftermath of the pandemic, China’s real estate crisis and the ongoing trade war, China’s moneyed middle-classes might buoy the domestic tourism industry for some time to come. But a cocooned China is hardly going to help the state of hostility that persists between Washington and Beijing. And those who believe in the flow of people between the West and China are sounding the alarm. “It seems almost disrespectful that people don’t want to visit the home of almost a quarter of humanity,” said the guidebook publisher Magnus Bartlett, who fears the West is “becoming estranged from China.”

A cocooned China is hardly going to help the state of hostility that persists between Washington and Beijing.

Where does this leave the humble China guidebook? To a Gen-Z reader, who came of age listening to podcasts or following TikTok influencers, this question probably has the same relevance as asking about the fate of the wireless radio and the phonograph. But reports of the guidebook’s death have long been exaggerated. People still listen to the radio. Vinyl records have outsold CDs since 2022. And in that year, Americans bought 5.8 million guidebooks and maps. While this isn’t back to the pre-pandemic level of 6.9 million, it certainly is an improvement on the 1.8 million sales made in the peak-pandemic year of 2020.

I asked a number of publishers and writers why guidebooks have endured. The reasons they gave were manifold, but all agreed that an expertly written, carefully curated guidebook is simply easier to browse than the internet, which is jammed with unchecked information and sponsored content. Publishing is, however, sales-led, and guidebook publishers are not rushing to update their China list. While Lonely Planet is scheduled to publish a new China guide later this year, APA Publications has put potential new China editions of both Rough Guides and Insight Guides on pause in favor of other Asian destinations.

As Sarah Clark, APA’s head of publishing, told me: “Obviously it’s really important because China is such an important country and it’s a gap in our list. But it has not been requested in the same way that, for instance, Japan has. … Japan is a very hot destination. Our American distributors, as well as our U.K. ones, are really keen on us producing guides to it and it reprints all the time.” British travel bookstore Stamford’s best-seller list for 2024 confirmed this trend: Lonely Planet Japan ranks number one, and The Rough Guide to Japan number six.

Speaking on the Personal Landscapes podcast in March 2024, author Alex Kerr said that Japan is now “one of the most visited countries in the world,” noting that “by the 2000s it was 8 million [visitors] a year, now it’s 30 million [visitors].” Kerr ventured that “Japan’s cultural richness,” including its tea ceremonies and Zen temples, are making it the obvious alternative for travelers who might otherwise have gone to China.

Admittedly, China does itself no favors with its oppressive security apparatus, restrictive cybersphere and insensitive urbanism. But the idea that travelers are shunning the Middle Kingdom is troubling, given the cultural diversity and historic depth that is overlooked in favor of the contemporary political narrative. China makes a particularly compelling case for traveling with a guidebook, due to its size, complexity and linguistic challenges. Yet the real perks are often found on a more human level: being offered someone’s bed for the night in an obscure corner of rural Hunan; sipping tea with a new friend in the second class car of a slow train rolling through craggy Guizhou. It is those person-to-person interactions while traveling that foster mutual understanding and humanize the nation. Without them, it is all too easy to fall into an “us and them” mentality.

In some respects, internet influencers have taken the place that travel writers used to occupy. Cities such as Chongqing and Shenzhen have become internet sensations due to their futuristic skylines. Vloggers title videos with platitudes about “a city of 20 million people you’ve never heard of” then feed you a seconds-long montage of exotic foods and weird looking buildings. Earlier this year, the American streamer IShowSpeed’s trip to China went viral on both sides of the Pacific, showing a modern, fun side to the nation that surprised some of his Gen-Z viewers.

But the Instagram effect, which has supplanted the Lonely Planet effect of the previous generation, can render places with over two millennia of recorded history as cheap clickbait. Witnessing selfie-stick wielding foreign tourists in Chongqing, it struck me that the Qing-era Huguang Guildhall or the WWII Stillwell Museum were being ignored in the rush to photograph a cable car swinging between two skyscrapers, or a train going through a high-rise building at Liziba Station. A guidebook reader would have at least known something of the city’s people and their story. But in an age where we have access to so much information, towering cities that were thousands of years in the making have been flattened into pixels on our smart phone screens, observed for a few fleeting seconds before the next kitschy story supplants it in the feed.

Still, a dwindling number of old-school wanderers can’t shake China’s spell. That includes Magnus Bartlett, who founded the first China travel guide in 1979. Now 81, the veteran photographer and publisher has just returned from a return trip to “the mainland,” 47 years after he first went. He traveled overland along the Yellow River, to ancient sites such as Xi’an’s Terracotta Warriors and Luoyang’s White Horse Temple, as well as to Yan’an, base of the Chinese Communist Party from 1935 to 1947. “It’s easy to get distracted by the bright lights of contemporary China,” he told me. “But now, more than ever, it’s a good time to go back to the roots … to get a reminder of what makes the place tick.”

In 2023, after the Covid pandemic was over, Bartlett attended a Moon Travel Guides 50th anniversary party in San Francisco. He told them, “now would be a better time than ever to produce a really great China guide.” ∎

Thomas Bird is a travel writer focused on Asia, where he has been based since 2005. He is a regular contributor to the South China Morning Post, and has written for publications including BBC Travel and Geographical Magazine. Bird has co-authored more than 20 guidebooks, and is author of Harmony Express (2023). He likes craft beer and the teachings of Zhuangzi.