Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

My education in Chinese cooking began in a drafty Beijing classroom in 2005. In a former elementary school nestled in the hutongs, a seasoned gray-hair chef taught at a blackboard, without recipes or a cookbook. The class’s purpose was to train students to pass the certification for the national cooking exam; we spent our time learning all the possible questions and answers that would come up on the test. Occasionally, the teacher would move us into a demonstration kitchen and lecture at a stove with leaping flames and we would greedily sample seafood cooked with the proper wok hei (镬气), a Cantonese term that is more popular in the West. As for our own cooking skills, those would be learnt after we passed our exam and got a kitchen job — by doing, not through books.

For me, cooking was a point of entry to understanding Chinese culture and history as a Chinese-American freelance journalist in Beijing. My first book Serve the People (2009) tracked my progress from novice cook to the founder of a cooking school, exploring the lives of those I met in China’s restaurant world. I provided recipes with each chapter, but they were mostly for color and context. I have never written a cookbook, maybe because I am intimidated by the technicalities involved in explaining how to cook Chinese dishes to a Western audience. Despite the deep understanding of Chinese cuisine that I have since amassed, I fear I still won’t be able to help someone far away from China, struggling with a wok, a cleaver and all kinds of unfamiliar, fermented sauces.

Chinese cooking is a difficult skill to translate. Historically, Chinese poets have had more luck translating the beauty of cooking into verse than Chinese cookbook authors have had in putting techniques onto the page. Before Chinese cookbooks existed, the 3rd century poet Fu Xuan (傅玄)described noodles as “lighter than a feather in the wind … fine as the threads of cocoons of Shu … as brilliant as the threads of raw silk.” One of the earliest Chinese cookery books with measurements appeared during the Song Dynasty, written by a rare literate woman surnamed Wu from Jiangsu, according to Chinese Gastronomy, a cookbook by Hsiang Ju Lin and Tsuifeng Lin, relatives of the early 20th century author Lin Yutang. Another five centuries went by before another gastronomic work of acclaim appeared, the poet Yuan Mei (袁枚)’s Recipes from the Garden of Contentment (随园食单), published in the late 18th century.

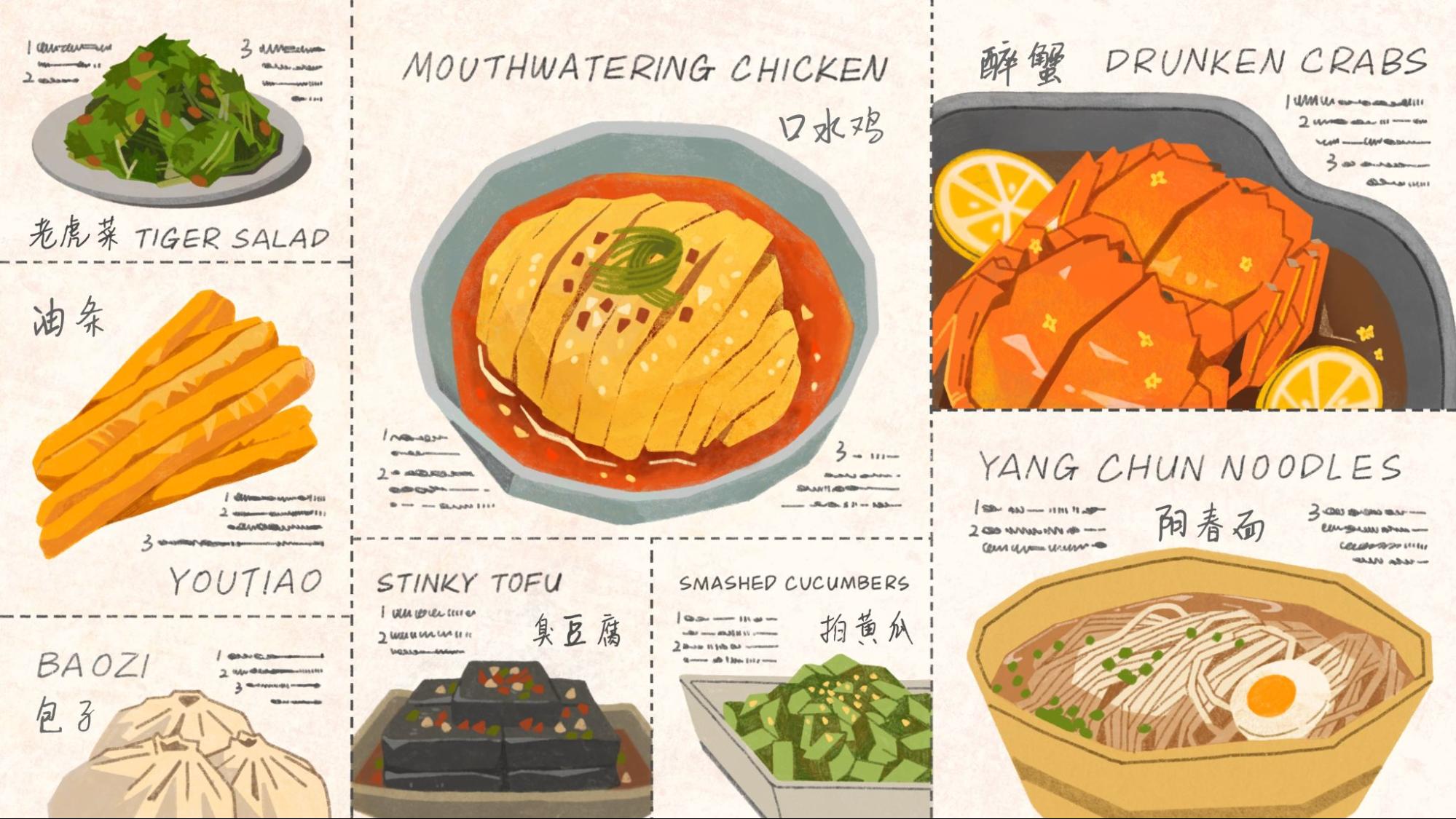

Cookbook authors attempting to translate Chinese recipes into English have even bigger hurdles. Western audiences often have a different conception of what Chinese food is, given how it has evolved into entirely different cuisines in America and Europe. Ingredients such as fermented black beans and broad bean paste are foreign to the average Western reader. Heavy woks and large cleavers can feel unwieldy to the novice. Translating ingredients and dish names is often a problem. (How does one translate koushui ji 口水鸡, literally “saliva chicken”?) Chinese chefs sometimes tenderize meats — chicken, beef or pork, ground or tenderloin — with their bare hands, which can seem crude to the outsider. (Similarly, some Western food habits seem barbaric to Chinese, such as dining with a fork and a sharp knife; in Chinese custom, steak and suchlike should be cut into small pieces before being served.) Techniques such as stir-frying are difficult to describe in words, requiring your senses of smell and vision to master the proper timing.

Would we ever expect tai chi or gongfu masters to teach their art through books? Why, then, do we have an expectation that we can learn how to cook Chinese cuisine through cookbooks? What is the purpose of cookbooks anyway, when both Western and Chinese audiences are migrating to YouTube and social media to learn cooking skills? Maybe it’s better to follow centuries of Chinese tradition: ditch the cookbooks and just learn by doing.

Would we ever expect tai chi or gongfu masters to teach their art through books? Why, then, do we have an expectation that we can learn how to cook Chinese cuisine through cookbooks?

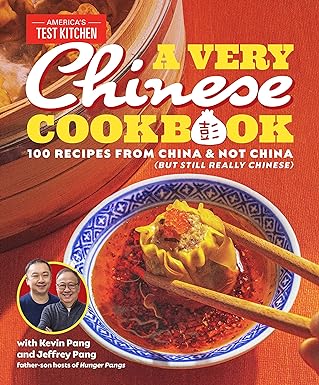

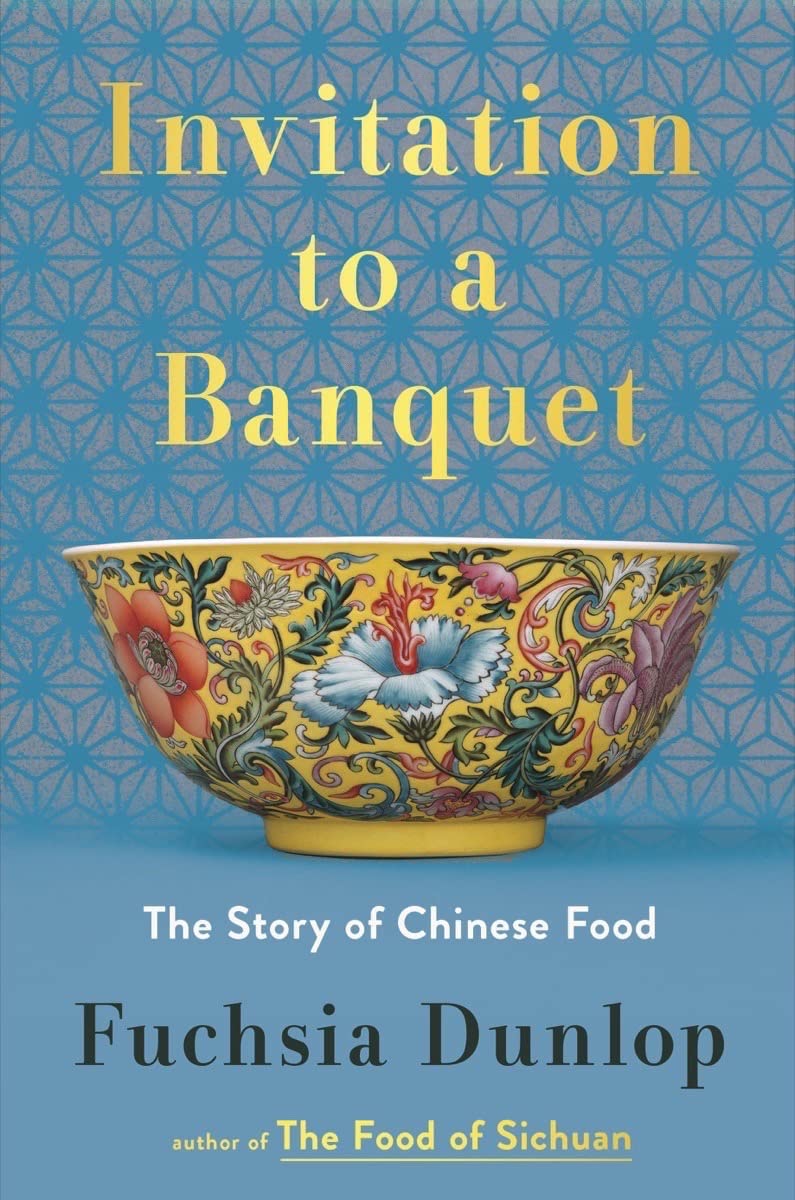

Yet, for all the culinary translation challenges that they face, books about Chinese food continue to be published, and they sell well. In China Books Review’s list of bestselling books, which they have kept since their launch in October 2023, several books about Chinese cuisine have featured in the monthly top five rankings, including A Very Chinese Cookbook:100 Recipes from China and Not China (But Still Really Chinese) by Kevin and Jeffrey Pang (America’s Test Kitchen, October 2023), Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food by Fuchsia Dunlop (W.W. Norton, November 2023) and Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories from the Island Nation by Clarissa Wei (Simon & Schuster, September 2023).

A Very Chinese Cookbook, to take an example, follows a tried-and-tested model of Chinese cookbooks that began in the mid 20th century: that of a Chinese immigrant’s quest to preserve and pass down recipes to the next generation. Jeffrey Pang, a Hong Kong native, immigrated to America in the 1960s, where his son Kevin was born in 1981. Years of strife ensued between the father “hanging on to his Chinese identity” and the son “desperately” trying to be American. Both were headstrong. Their relationship was “cordial but indifferent,” Kevin writes in the introduction.

A decade ago, Jeffrey began sending his son links to videos of Chinese recipes he made and uploaded onto YouTube. Kevin, then a metro desk reporter for The Chicago Tribune, ignored them. “In the history of parental email forwards, roughly 0.001 percent have been worth opening,” Kevin writes. Then Kevin’s paper gave him a coveted job in the food section, and for the first time father and son shared a mutual interest. “My father never taught me to swim or to ride a bike, but he did teach me how to tell a good dim sum restaurant from a great one.”

A Very Chinese Cookbook is a product of America’s Test Kitchen, a publisher of cookbooks and the magazine Cook’s Illustrated. It claims to spend $11,000 on each recipe it tests (“an all-in cost,” the Chief Operating Officer Evan Silverman told me, which presumably means that it includes salaries). This, their first complete Chinese cookbook, has a rigorous introduction with lists that break down ingredients, equipment and techniques. Each chapter contains authentic Chinese dishes such as Smashed Cucumbers, Tiger Salad and Mouthwatering Chicken (a much better translation than “Saliva Chicken”) interspersed with dishes that originated outside of mainland China such as Mongolian Beef, Almond Chicken and General Tso’s Chicken. The precisely explained methods and measurements are admirable but leave me wondering about an inherent contradiction in Chinese cookbooks: the more precise and exacting they are, the less authentic it feels.

A tried-and-tested model of Chinese cookbooks is that of a Chinese immigrant’s quest to preserve and pass down recipes to the next generation.

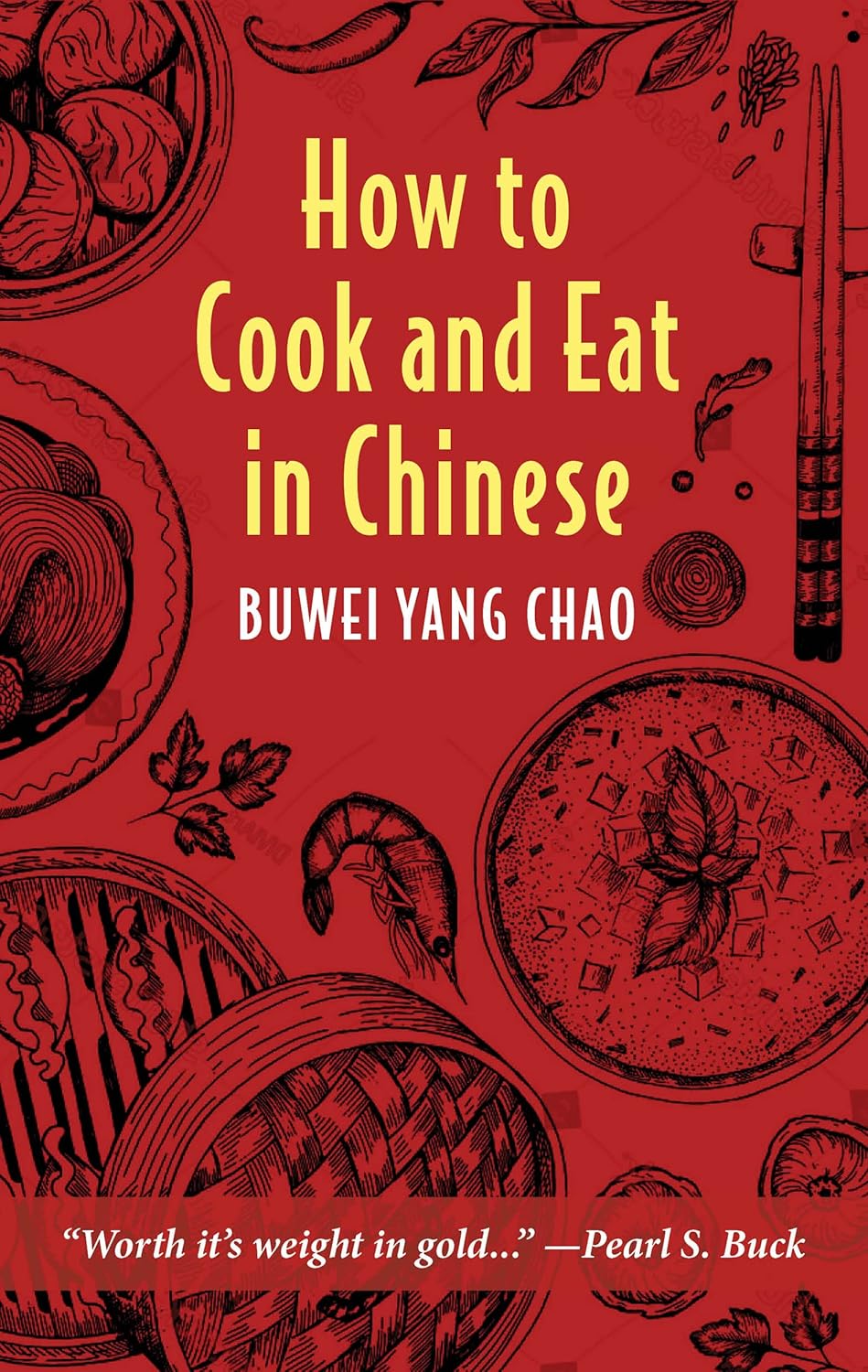

The first Chinese cookbooks in English came out of foreign missionary communities in late 19th century China, the product of cooperation in the kitchen between Chinese cooks (who were mostly illiterate) and anglophone housewives. In the early 1900s, small publishers in the U.S. began distributing Chinese cookbooks, but it was only in 1945 that a truly authentic Chinese cookbook appeared, How to Cook and Eat in Chinese by Buwei Yang Chao. Chao, born in Nanjing, China in 1889, split her life between the United States and China in the 1920s and 30s before she and her husband, Yuenren Chao, a Harvard-trained linguist, settled down in Berkeley, California after World War II. They were part of a small but influential group of Chinese intellectuals in America that included Lin Yutang and Hu Shih.

Chao was one of China’s first female physicians and opened the country’s first birth control clinic in Beijing. She was an adept home cook and dabbled as a restaurateur in China. At Tsinghua University, where her husband taught, she opened a restaurant because she was unhappy with the campus culinary offerings. (I am currently writing a biography of Chao, tentatively titled The Formidable Mrs. Chao, which will be published next year.)

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese introduced Americans to the concept of “stir-fry” — a word that she and her husband invented, along with “pot stickers” — and gave her readers a real view of how China’s then-population of 500 million ate. She ignored what Chinese restaurants in America served, boldly leaving out inauthentic recipes that Americans associated with the cuisine, such as chop suey. Chao possessed both culinary knowledge and eloquent writing skills (rendered into English by her husband and daughter, Rulan Chao Pian, who, at Harvard, later taught Mandarin to students including Perry Link). Detailed chapters explaining ingredients, equipment and methods are accented with sharp insight and humor. The recipes themselves are simple, easy to follow and endlessly adaptable; the very lack of precision is what makes the book authentic. That was, and is, the way that Chinese cooked.

As in A Very Chinese Cookbook, family strife is part of How to Cook and Eat in Chinese. Chao openly writes about the quibbles she had with her family members over the cookbook. In the author’s note (one of the most humorous I’ve encountered) Chao writes: “[When] I call a dish ‘Mushroom Stir Shrimps,’ Rulan says that’s not English.” Her daughter contends that “Shrimp Stir-Fried with Mushrooms” would be preferable. Chao continues:

I don’t know how many scoldings and answerings-back and quarrels Rulan and I went through, and if kind friends … had not come to our rescue to get the book done in a last midnight rush, the strained relations between mother and daughter would certainly have been broken. … Now that we have not neglected to do the making-up with each other after our last recipe, it is safe for me to claim that all the credit for the good points of the book is mine and all the blame for the bad points is Rulan’s.

Only somebody who knew Chao could tell that she was joking.

The Nobel-Prize winning American author Pearl S. Buck enthusiastically supported Buwei Yang Chao’s work, and saw in the cookbook a mission to strengthen ties between the U.S. and China during World War II. She convinced her second husband Richard Walsh, head of an American publishing house, to print it. Buck added a glowing forward. By the time the book was released, World War II had ended, and Americans — no longer subjected to rations — were eager to find new inspiration in the kitchen. The book sold upwards of 100,000 copies and went through 22 printings in its lifetime. Chao died in 1981 but the popularity of her cookbook continues; a Chinese publisher discovered the book and published it in Chinese in 2017.

Buwei Yang Chao’s was first among a slew of Chinese cookbooks released in America after World War II by Chinese women whose families fled Communism for the U.S. or Taiwan. Fu Pei-Mei was born in Japanese-occupied Manchuria in 1931 and moved to Taipei in 1949. She authored more than 30 books about Chinese cooking, which provide an almost encyclopedic trove of recipes from China’s various regions. Writing in both Chinese and English, she found an audience among the American diplomatic corps in Taiwan, and later among the growing Chinese diaspora in the U.S. and beyond. (She is also the subject of Michelle T. King’s biography Chop Fry Watch Learn, shortlisted for China Books Review’s 2024 book prize.)

Meanwhile, in the U.S., Joyce Chen, who grew up in a prominent family in Beijing and also fled her homeland in 1949, rose to prominence with her eponymous cookbooks, a series of restaurants in Cambridge, Massachusetts and a cooking show on PBS with the same set and producer of Julia Child’s The French Chef. The unimaginatively named “Joyce Chen Cooks” debuted in 1966, making Chen the first woman of color to host her own nationally-syndicated television show. Cookbooks also came out by other daughters of elite Chinese families who had made their homes in the States, including Florence Lin (a relative of Lin Yutang), Grace Zia Chu and Eileen Yin-Fei Lo. Male voices joined the chorus in the 1980s, with chefs such as Martin Yan, Ken Hom and Ming Tsai, each of whom became television personalities in addition to cookbook authors. (Tsai’s fame recently took a hit after he made inappropriate comments about women in the food and beverage industry.)

For generations, these books relied on the authors’ memories of Chinese cuisine, trading on it to an American audience who lacked access to China after the Communist Revolution. Even after the death of Mao in 1976 and during the opening of China in the 1980s, knowledge of Chinese cooking in the West relied on migrant chefs and cookbook authors to showcase the cuisine from afar. But that was about to change.

Buwei Yang Chao’s was first among a slew of Chinese cookbooks released in America after World War II by Chinese women exiles.

By the end of the 20th century, cookbook authors — and the rest of the world — had greater access to China. A new formula developed: authors were able to spend substantial time in China and no longer had to rely on memories of Chinese diaspora cooks.

The British author Fuchsia Dunlop, on a scholarship from the British Council in the 1990s, moved to Chengdu to learn Chinese, then stayed to attend the Sichuan Higher Culinary Institute (四川高等烹饪学校) as its first Western student. She cooked alongside chefs in professional kitchens across Chengdu. “Speaking and reading Chinese has been central to everything I’ve done,” Dunlop told me. “As the Chinese say, ruxiang suisu, which translates roughly into ‘When in Rome, do as the Romans do.’” Her first cookbook, Sichuan Cookery, came out in 2001 in the U.K. and 2003 in the U.S. In the following 20 years, W.W. Norton has released six Chinese cookbooks by Dunlop, mostly regional in nature, plus a memoir titled Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper (2008).

In her latest title, Invitation to a Banquet (2023), Dunlop abandons recipes. Though she writes in first person, it’s more of a manifesto than a memoir. Her aim seems to be spreading the gospel of Chinese cuisine, which she does with almost religious fervor. A sexual undertone imbues many of her descriptions, such as when she details her initiation into a feast of drunken crabs in Shanghai. The crab is “ice cold and vividly slimy, with a scintillating kick of liquor, the flesh of ovaries … made me shiver with pleasure … they were as creamily voluptuous as foie gras, yet simultaneously as brisk and arresting as a raw oyster.”

The allusions to foie gras and oysters elevate Chinese cuisine, giving it the same reverence paid to French food. Dunlop also uses the word terroir frequently, and she points out the double standards in Western perceptions of Chinese versus European cuisine. In a chapter titled “The Lure of the Exotic,” she writes:

[When] the Danish chef Rene Redzepi puts ants or reindeer pizzle on the menu at his restaurant, Noma, he’s a culinary genius … Yet if a Chinese chef works wonders with a duck’s tongue or an elk’s face, he’s a desperate peasant or a cruel barbarian.

Dunlop writes skillfully and beautifully about Chinese cuisine. She continues to travel to China on a regular basis, engaging with the country in an enviable way in these politically-sensitive times. But it brings up a conundrum that many writers, scholars and businesspeople face these days when it comes to China. Does our access compromise the way we think about it? I worry that Dunlop’s mission, however honorable, makes her susceptible to sounding like she’s part of China’s propaganda machine.

Her book contains many passages about eating exotic wildlife, but it’s not until late in the book that she adds that she does not condone the practice. She’s never been the type of writer who explores the underbelly of China’s food industry, where sexism, the use of pesticides and other chemicals, and general food safety are concerning. Dunlop contends that as China becomes more politically isolated from the West, the more committed she feels to working on the topic of food, which she argues can be an area of engagement and apart from politics.

Fuchsia Dunlop’s aim seems to be spreading the gospel of Chinese cuisine, which she does with almost religious fervor.

Yet in today’s China nothing escapes politics, not even food. Clarissa Wei’s bold and brilliant book Made in Taiwan suggests exactly this. Wei, a Taiwanese-American who grew up in California, moved to Taipei in 2020 and rejects the word “Chinese.” She writes in her introduction: “Our food isn’t a subset of Chinese food because Taiwan isn’t a part of China.” While many Taiwanese dishes have Chinese roots, she adds that “physical and diplomatic isolation, entirely separate governments, and most important, a nascent yet powerful Taiwanese identity movement … have given shape to a re-defined food culture that’s completely and unquestionably unique.”

Most mainland Chinese would have no idea what to do with many ingredients in Wei’s book, including Taiwanese soy paste (醬油膏), dried flounder (扁魚, similar to Japanese bonito flakes), shacha sauce (沙茶, a gritty dark brown sauce made with dried seafood, shallots and garlic) and an ingredient called maqaw (馬告) used by the indigenous Taiwanese population. The cookbook’s recipes and photography feature vibrant dishes such as Or A Tsian (蚵仔煎), an oyster omelet with a sweet pink sauce that, according to legend, was invented by the 17th-century Chinese pirate king Koxinga. We learn about Taiwanese breakfast burgers that come with a slice of ham, a fried egg, cucumber slices and Kewpie mayonnaise (a dish I fondly remember from my childhood visits to the island); Taiwanese “tempura,” playfully called tianbula 甜不辣 (“sweet not spicy”) which, made of fish paste, bears no resemblance to the Japanese variety; and desserts such as taro and tapioca balls with shaved ice. Wei gives her dish names in English, Chinese characters, pinyin and Tai-lo (the official romanization system for Taiwanese Hokkien), and also mentions neologisms such as food with a “Q” or “QQ” texture, meaning chewy or gummy.

Wei’s cookbook goes beyond merely instructing readers how to cook the dishes. By presenting Taiwanese cuisine in its full complexity, she sometimes presents a barrier to entry so high as to put people off actually trying it for themselves. For example, her recipe for stinky tofu involves making one’s own brine with rice, foraged amaranth greens, water spinach and Taiwanese rice wine (“open a window or turn on the stove’s exhaust fan to its highest setting”). In her recipe for fried crullers or youtiao, she explains without sentimentality that incorporating ammonia bicarbonate may result in filling your kitchen with a urine-like scent. When I got to her section on kueh (粿), a sweet or savory pastry made of sticky rice and shaped with molds resembling turtles, I finally understood Wei’s mission. These culinary traditions — whether in making stinky tofu, fried crullers or kueh – are fading. She aims to make readers in both Taiwan and the outside world see their importance and preserve them.

Authors such as Dunlop and Wei understand that the mission of Chinese and Taiwanese cookbooks has changed, with the wide availability of Chinese recipes on the internet. These days, when I want to look up a recipe I can go on YouTube and search the name of the dish in Chinese; invariably, at least a couple of authentic recipes pop up. For the English-language reader, the excellent website The Woks of Life, created by a Chinese-American family of four, provides an encyclopedia of easy-to-follow Chinese recipes, along with guides on everything from how to buy a wok to how to make ground meat (often a necessity due to the higher fat content required for Chinese recipes, relative to the leaner ground meats found in Western supermarkets).

The Woks of Life hit a million page views per month in 2016. In 2022, the family published a cookbook named after the website. But as Sarah Leung, one of the two daughters in the family writes in the book: “Food is never just about the recipe.” The cookbook dives into their stories of immigrating to the United States, running a Chinese restaurant in the Catskills and the family’s discovery of authentic Chinese dishes after moving to Beijing in 2011.

Through its website, cookbook and videos, The Woks of Life takes a multi-faceted approach to teaching Chinese cooking. We’ve come a long way since the 1945 publication of Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese. While the perception of China has swung wildly since World War II, passion for Chinese food has remained high. Though demand for books about the subject is unabated, authors need to be ever more strategic. As Sarah Leung notes, books about Chinese food shouldn’t just provide step-by-step descriptions of how to make it. They need stories about “how you enjoy it, share it, and pass it on.” ∎

Jen Lin-Liu is an author focused on Chinese cuisine and history. She has written two culinary memoirs, Serve the People (2009) and On the Noodle Road (2014), and is author of the forthcoming Formidable Mrs. Chao: The Story of China’s Julia Child. Lin-Liu is the founder of the Beijing cooking school Black Sesame Kitchen and has worked as a culinary consultant for the D.C.-based chef Peter Chang.