Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed: From Forest Farm to Sawmill: Stories of Labor, Gender and the Chinese State by Shuxuan Zhou (Washington University Press, July 2024).

At 8 a.m. on a Tuesday in early July, the Worker Center in Seattle’s Chinatown was packed with immigrant laborers. The commotion was not unusual (most regulars there work morning shifts at massage parlors) but the reason for this gathering was an academic book launch. Shuxuan Zhou, a sociologist and organizer of the Massage Parlor Outreach Project, was there to present From Forest Farm to Sawmill, a history of the Chinese women who lived and worked in the state-run forestry industry of Shaowu, Fujian province, from the high socialism of the Mao era through privatization in the 1990s to labor protests in the Xi era.

Zhou projected portraits of female workers on a screen and asked attendees to read quotes from them. A woman with short, neat curls and a cigarette in her hand gazed directly at the camera as I read her recollection of the Great Leap Forward as a time of “great fun”:

As a leader of the village Women’s Federation, my responsibility was to mobilize women to work on the collective farm. … To mobilize them, we visited their homes to call on them one by one. We just cut their hair, the women’s braids. It was so crazy! Some of them didn’t want their braids to be cut, but we didn’t do too much talking. Having braids cut off their means of going out to work. To emancipate women, women must go out to work, so men and women can be equal.

Extreme? Perhaps, but her words had a certain logic to them. China in the late 1950s desperately needed labor to rebuild the economy after decades of war and upheaval. Drafting women into the labor force seemed an elegant solution, and one that dovetailed with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s ideas about gender liberation. Yet feudal social structures that conceived of women as household property were an obstacle. Cutting women’s braids was a symbolic and brutal means to achieve labor participation goals quickly. As Mao Zedong put it in a 1927 report on a peasant uprising in Hunan, “Proper limits have to be exceeded in order to right a wrong, or else the wrong cannot be righted.”

This stick came with a carrot. The state promised work unit-run childcare facilities and paid leave and benefits for women during menstruation, pregnancy and breastfeeding. However, as From Forest Farm to Sawmill reveals, this “alternative” was never realized in a way that truly benefited every working woman. Zhou exposes the “dark side of the moon” behind the socialist rhetoric, revealing the gap between the idealized vision of gender equality under Mao and the lived realities of working women. She uses oral and photographic history to tell two stories. The first explores the lives and labor conditions of the women upon their arrival at the forestry. The second documents their lives after the end of the Mao era, and how they used novel protest tactics to win compensation for their neglected labor during privatization in the 1990s and 2000s.

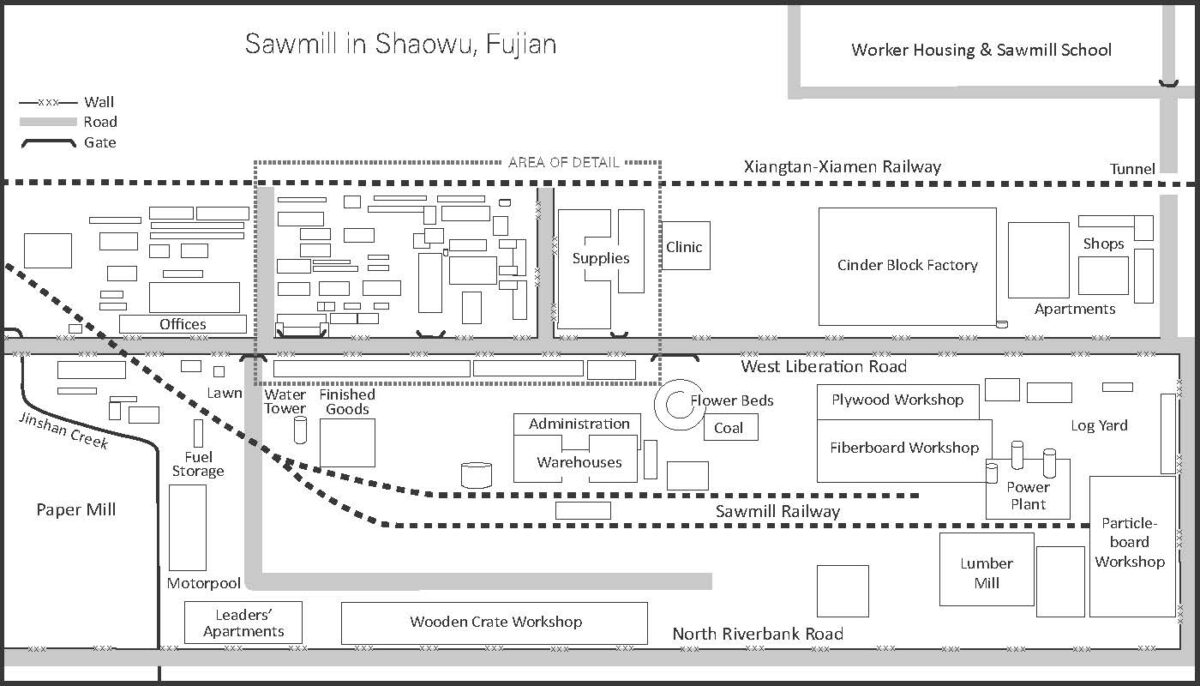

The book focuses on the Dragon Lake State Forest Farm in northern Fujian. Established in 1958, the farm, which included state-run logging camps and sawmills, was staffed primarily by workers recruited from Shandong province. Tens of millions of workers migrated to Fujian, lured by promises of plentiful food and good jobs — both of which were scarce in populous but impoverished Shandong. Most of the recruited workers were men. To stabilize this all-male workforce, the state allowed them to bring their wives and children.

On arrival, these women were made “dependent workers,” a Maoist class which was not offered the same benefits as their “state worker” spouses. For example, lower pay and lower rations of grain were allocated. They were also assigned tasks considered “lighter” than those of the men. While men felled trees and transported logs, the women worked alongside them: stripping branches and peeling bark, cutting fire breaks, and burning clear-cut areas to prepare the soil for the next round of tree planting.

Zhou perceptively observes that the state didn’t define “heavy labor” by physical strain but by technical skill. Women did all their work by hand, while men were assigned tasks involving machinery. This gendered division led to wage inequality and entrenched stereotypes about women’s inability to handle machines. Yet these women bore the burden of both backbreaking labor and childrearing.

Did these women at least enjoy the childcare benefits that were promised? Not all of them. While sawmills offered nurseries to enhance productivity, places were limited and required joining a waitlist. Some women were forced to bring their children to the sawmill or to leave them in the care of older siblings. Others hired local farmers as nannies. The cradle-to-grave welfare system that the Party had promised did not reach everyone.

The women were made “dependent workers,” a Maoist class which was not offered the same benefits as their “state worker” spouses.

Stories of “speaking bitterness” (诉苦) are a focal point of Zhou’s book. An oral tradition in rural China used by women and the elderly to seek justice, “speaking bitterness” was co-opted by the Party for political campaigns, beginning with land reform. Party activists encouraged peasants to recount the exploitation and suffering they had experienced at the hands of landlords, and to praise the Communist Party’s revolution for bringing them a better life. Speaking bitterness mobilized people to struggle through the creation of a universal, oversimplified narrative. Workers who grew up during that era later adopted the same method to self-organize in response to unfair compensation issues following the privatization of state-owned enterprises.

Injustice towards female “dependent workers” continued after the death of Mao. In 1977 unemployment was widespread. The central government required state-owned enterprises, including the Dragon Lake State Forest Farm sawmill, to reduce labor costs. The sawmill adopted a “replacement recruitment” system, in which a retiring worker could select one child to replace them as a state worker. Many families prioritized sons to replace them, while daughters continued to work in dependent production teams. In the 1980s, the state relinquished its monopoly on timber, spurring the creation of village collectives to log forests and operate sawmills.

As China transitioned from state socialism to state capitalism during the reform era, the state-owned sector was downsized and increasingly privatized. In the 2000s, Dragon Lake State Forest was reclassified as an ecological public welfare forest (生态公益林). Commercial logging was banned, and the sawmill was sold to private wood-processing companies, leading to most of the state workers losing their jobs. Around 2013, the mill was demolished. State employees received compensation. But the female “dependent workers” got much less — or nothing at all. Women had planted the trees that allowed the forest farms to be sold for massive profits, yet they got little in return.

In 1998, female dependent workers and their state worker husbands staged brief protests against unfair compensation for women in the form of sit-ins, petitions and by suing the Shaowu government. But with prospects of success slim and school-aged children to worry about, the protests died out quickly. Sixteen years later, after many of the women retired and their children were grown, they began to fight again. On February 26, 2014, around 200 female dependent workers, aged 50 to 80, protested in front of the Shaowu government. They passed out a petition for signatures and read it out loud. After an hour and a half, they broke through a police cordon and occupied the Shaowu city hall. Afterward, they kept up almost daily demonstrations and meetings with representatives from the city government.

While promising to address their demands, city officials arrested a leading male activist to intimidate the others. The women, meanwhile, adopted socialist-style propaganda language in their slogans — such as “protect the state-owned land and their collective property from slipping into the hands of private owners” — to make it difficult for the state to crack down on them, and 80-year-olds lead their marches to make the police reluctant to use force. They articulated four major demands, primarily compensation for dependent workers, and studied the relevant laws and policies so thoroughly that even government representatives were surprised to find themselves less knowledgeable than the grannies.

State repression was not the only obstacle they faced. Their male former colleagues at the state-run farms met their protests with derision, even though they too detested privatization. As one of them commented:

But how can the state let you, a group of women, win by making all these noises? Just use your brain to think it over. How is it possible? If you achieve your goal, I will swallow this beer bottle.

The women collectively retorted, “Because men are all cowards, and we women are fearless.”

Their protest lasted nine years and ultimately secured 17.9 million yuan (about $2.5 million) in compensation in 2023. That sum was distributed across more than 500 workers, awarding each approximately 36,000 yuan ($5,000) — a considerable sum given that the annual per-capita net income in rural Fujian at the time was only 56,153 yuan. Yet, considering the labor and time they had invested over the years in their struggles, the compensation each individual received wasn’t that much — not even enough to buy a car. What may have offered them greater comfort might be a sense of justice being upheld, and the bonds of solidarity forged through their collective resistance.

The emancipation of Chinese women was never a benevolent gift handed down from male leaders on high.

You won’t find women’s wisdom in CCP propaganda, or in the male-written histories of China. But feminists who understand the Party know that the emancipation of Chinese women was never a benevolent gift handed down from male leaders on high. It was hard-won, claimed through strategic struggle and negotiation by feminists within the Party. Whenever I study the history of women’s movements in socialist China, I’m struck by the peril of their position, and at the same time deeply moved by their resilience. Amid low productivity, scarce resources and the weight of entrenched patriarchal traditions, these women dared to propose progressive visions such as childcare benefits, equal pay for equal work and women’s participation in public and political life. Yet in implementation, these ideals were often compromised. It is heartbreaking to witness the gaps between vision and reality.

For years, I’ve felt frustration at the repeated defeat of feminist struggles within the CCP. Much of the hard-earned legacy of women’s liberation was eroded during the reform era, as official policies shifted from encouraging women’s public participation to pushing them back into marriage and domesticity. This reality often leaves me disheartened. Yet Zhou’s stories of working women’s resistance reminds me to redirect my focus, from the disappointing fate of elite feminists to those who continued to fight on the ground with creativity and defiance.

For Zhou Shuxuan, this book was a personal project. Her father worked at a Fujian state-run sawmill, and was among those 3,000 workers laid off in 2000. She began interviews for the book in 2008, talking to her father’s former coworkers, and tenderly depicts the struggles and resistance of working women in this community she knows so well. These are the stories of our mothers’ and grandmothers’ generations — the songs of fighters who came before us. The book’s dedication is “TO ALL RAGING nainai AND popo.” I believe it is their rage, and that of all women who fight against gender injustice, that propel the feminist movement in China today. ∎

Header: Former workers gather at a partially demolished sawmill in Fujian to draft a petition arguing for fair pensions, 2014. (Shuxuan Zhou)

Zheng Churan is a Chinese feminist activist. Since 2012 she has organized young women in China to engage in policy advocacy and public education, and has also advocated for female worker’s rights. In 2015 she was detained by the Chinese government for her activities, along with other activists known collectively as the “Feminist Five”.