Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

The untimely passing of Li Keqiang at age 68, in late October, marked the end of an era of reform in China’s economy. Li was associated with that reform, but delivered next to nothing to achieve it. Instead, he was sidelined as Premier by Xi Jinping, and as a result a deeply troubled economy has emerged, along with a malaise that is hanging over society and business. This leaves us asking: what has gone wrong in China? And what, if anything, can be done to put it right?

Throughout his career, Li was a leading advocate of economic reform, favoring less regulatory red tape, restrictions on the role of the government and greater use of market mechanisms. Prominent among extensive reform proposals, unveiled at the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress in November 2013, was the elevation of the role of markets in China from having a “fundamental” to a “decisive” role in the allocation of resources.

Those reforms never saw the light of day. Following the Chinese financial crisis of 2015-16 (in which the stock market tumbled, the yuan came under significant pressure and China lost about $800 billion from its international reserves), they were extinguished in the wake of an increasingly state-centric and Party-oriented governance. The delayed Third Plenum of the 20th Congress, expected later this year, could illuminate the Party’s thinking about how it will address the nation’s mounting economic headwinds — but there is no flag-carrier for liberal reform anymore.

A deeply troubled economy has emerged, along with a malaise that is hanging over society and business.

It is against this backdrop that a debate over who killed the Chinese economy has raged in Foreign Affairs. Adam Posen, of the Peterson Institute, argued that during the last few years, Xi Jinping’s Zero-Covid policies and reversion to state control have stymied the confidence of private firms and entrepreneurs, undermining the dynamism of China’s economy. Responding, Zongyuan Zoe Liu of the Council for Foreign Relations, and Michael Pettis of Peking University, argued that China’s economic problems pre-dated Covid and Xi by a considerable margin. Xi inherited a systemically flawed economic development model when he came to power, they posit, along with stunted population growth and low productivity; his failure was to exacerbate this by becoming reliant on centralization, keeping the old dysfunctional model on the road.

These alternative versions of what went wrong are, in some ways, mutually supportive. All analysts agree on the principal flaws and problems in China’s economy, which I outlined in my book Red Flags (2019). These include: excessive levels of debt in local government, state enterprises and real estate; under-consumption; over-investment and misallocation of capital; the consequences of rapid aging in demographics; weakness in productivity growth; a more controlling and repressive governance; the subjugation of private firms and entrepreneurs; and, most recently, commercial and business decoupling, now rebranded as de-risking.

Yet the rival diagnoses of China’s weakening economy carry profoundly different policy implications. If, as Posen argues, China’s economic problems are attributable to recent policy errors made by Xi Jinping (notably state intrusion into day-to-day commerce), then the treatment is simple: Xi should simply back off, re-set, and encourage private firms and entrepreneurs. Yet Posen is not optimistic that the autocrat who caused China to catch “long economic Covid,” as he terms it, can cure the disease.

Pettis retorts that this gets the causality backwards: the shift towards greater control and repression is the result, not the cause, of China’s faltering economy. While China was ripe for economic reform in the mid-2000s, powerful constituencies and beneficiaries in its political institutions persisted with a state model that gave rise to capital misallocation, inefficiency and imbalances. Managing these systemic problems, while trying to keep the political model intact, necessitated a strengthening of the role of Party and government at the expense of households and private firms. Pettis thinks Posen’s solution — to reduce government intrusion — might have a marginal effect, but China’s model really needs a total overhaul, involving extensive political as well as economic reform. The chances of this happening on Xi’s watch are essentially zero.

An alternative, more optimistic, assessment of China’s prospects is served up by London School of Economics Professor Keyu Jin (whose father, Jin Liqun, was once China’s Vice Minister of Finance, and is the inaugural President and Chair of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank). In The New China Playbook (Viking Press, May 2023), she acknowledges the breadth of economic problems in China, but asserts that China’s unique fusion of strong state capacity at the macro level, with market mechanisms and private firms at the micro level, is just the ticket.

This was certainly a feature of the reform and opening up era, but Jin fails to properly address the harsher business environment since Xi came to power, and the state’s unwillingness to accept market outcomes. For Jin, the new economic playbook is written by a younger generation of consumers and workers, who are market-savvy, innovative and entrepreneurial. This may be true of the educated, urban elite, but broader factors of general malaise, occupational immobility, educational shortcomings, rising unemployment and the social phenomena of “lying flat” (tangping) and “let it rot” (bailan) all escape her sustained attention.

In Jin’s view, China’s new model has abandoned loose regulation and swift growth for the sake of slower and saner growth, which will be more orderly, regulated and monitored — based on innovation and technology, and sustainable through self-reliance. This optimism certainly resonates with China’s undeniable economic heft. It is the world’s second-biggest economy and its biggest exporter. The nation accounts for about a third of global manufacturing, and no amount of supply chain recalibration will, for the moment, match the scale and networks that China offers to big multinational firms. China not only does manufacturing cheaper and more efficiently than any other nation, but it is also a key player in several advanced technologies, including electric vehicles, batteries, renewable energy and artificial intelligence. Xi’s emphasis on “new productive forces” at the frontier of science and technology speaks to both an ambition to dominate abroad, and an aspiration to create wealth at home.

Ambition and aspiration are easy to articulate. Realizing them is a more challenging task, given that this new path hinges on sound governance and robust, flexible institutions. Jin brushes over these sensitive political factors in her book, both historically and prospectively. Her optimism sits uncomfortably with the structural problems weighing heavily on China’s economy, and the constrictions that its Leninist politics places on policymakers. Jin provides a vision of overcoming inequality, nurturing soft power and innovation, finding new sources of growth, and cooperating with the U.S. Yet, without politically credible implementation and governance strategies to back it up, this is perhaps little more than a wishlist.

Jin fails to properly address the harsher business environment since Xi came to power, and the state’s unwillingness to accept market outcomes.

While it would be churlish to overlook China’s islands of technological and commercial leadership, it is also worth pointing out that these new, modern sectors represent a relatively small proportion of the nation’s economy (certainly compared to more traditional sectors such as real estate, retail, wholesale, finance and manufacturing). Innovation really comes into its own as it spawns changes in the capacity of those traditional sectors to boost productivity — yet the evidence that Party-state directives and industrial policies will promote such change is sparse.

We must remember that technology and commerce, and having household corporate names, do not necessarily signify enduring success. Japan had all of this 40 years ago. Sony, Toyota, Hitachi and Mitsubishi were among many assets on Japan’s calling card, frightening American leaders and economists in the 1980s into thinking that it would out-compete and overtake the U.S. Instead, it became clear that having world-class technology firms offered no protection against the systemic macroeconomic problems that led to the faltering of the Japanese economy soon after.

It is not for nothing that analysts at Goldman Sachs, and an array of China watchers (including myself), have started to refer to the “Japanification” of China. While contemporary China does not quite fit the Japan template of the 1980s and 1990s — China’s income per head is less than 20% of that in the U.S.; Japan’s in the early 1990s was 1.5 times larger — their economic models look very much alike. They present many similar features, including high debt, overvalued real estate, capital misallocation, rapid aging, and institutional or political barriers to reform. On the other hand, China’s property bubble is not as exaggerated; its debt does not stretch to most private firms; and the government has more policy tools to influence the economy, as well as the shield of capital controls. Yet, as China flirts with deflation, the risk of Japanification is rising.

China’s economy has reached the end of extrapolation from its seemingly unstoppable upwards curve.

Other commentators refer to “peak China.” This should not be taken literally: a precipitous decline is not expected any time soon. The state will not allow the financial system to implode; capital and other commercial controls will continue to offer protection or insulation; and it is impossible to predict a Soviet-style political collapse of the Chinese Communist Party. A more accurate term might be what Charlie Parton termed “plateau China.” It seems likely that China’s GDP growth limit is now no more than 2-3% per year, on average, and this might be even less if the government continues to avoid market reforms. The window for China’s GDP to surpass the U.S. is almost shut. That gap could indeed widen, as it did in 2023 for the first time in 30 years.

The Party is clearly wrestling with this conundrum, because the rhetoric of its core leader and senior officials is couched in terms of balancing growth on the one hand, and security on the other. Xi Jinping leans more to the latter, despite offering rhetorical support for the former. But the regurgitation of aspirational goals is no substitute for meaningful changes in policy direction. Investors have all but abandoned the Chinese stock market, and foreign firms are increasingly diversifying their investments and production into other countries, in and beyond Asia.

China’s economy is too big to fade dramatically, but it has reached the end of extrapolation from its seemingly unstoppable upward curve. The nation is only as secure as its medium-term economic prospects, and these are more vulnerable now than they have been for decades. Without a thorough reboot of its development model, the middle-income trap China fears draws ever closer. ∎

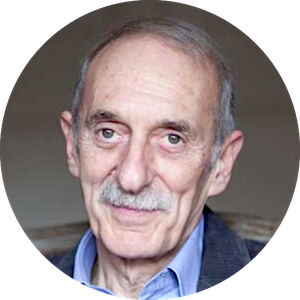

George Magnus is a research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre, and at the SOAS China Institute, London. Previously, he was Chief Economist and Senior Economic Adviser at UBS. He is the author of Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy (2019), Uprising: Will Emerging Markets Shape or Shake the World Economy (2010) and The Age of Aging: How Demographics are Changing the Global Economy and Our World (2012).