What a prolonged dreadful dream! Who can tell it? It cannot be told, nor even imagined, but I will try to write something of our experiences. We kept getting into closer and closer quarters; the darkness thickened; still we kept hoping, looking, praying for our coming troops. … Some nights and days the firing has been most frightful. At first it was the Boxers who attacked us; now it is the armed Chinese soldiers with their small arms and large foreign guns. … The blowing of their horns, their yells, and the firing of their guns, are the most frightful noises I ever heard.

These anxious lines come from a letter written by Sarah Pike Conger, an American woman living in the diplomatic district or “Legation Quarter” of Beijing, on July 7, 1900. The events she describes were part of a crisis best known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion, in which bands of North Chinese villagers launched a crusade in the late 1890s to rid China of Westerners and Chinese Christians. By mid-1900, the insurgents had gained the backing of the Qing dynasty (hence calling them “rebels” is misleading) and surrounded Beijing’s diplomatic district for 55 days, in what became known as the “Siege of Peking.”

Conger’s missive was included in her book Letters from China: With Particular Reference to the Empress Dowager and the Women of China, published in the United States in 1909. Her husband, Edwin H. Conger, was the American envoy to the Qing court. With the couple’s daughter Laura, and one of their nieces, in early July they moved into the British Legation from the smaller American one nearby — seeking safety in the biggest and most defensible compound in the Legation Quarter, as had other diplomatic families. “We are all one now,” she wrote, “the foreigners here are one people.”

Conger penned the above letter a third of the way through the siege, which began on June 20 and ended in mid-August. The siege imperiled the lives of diplomats from many countries and their families, and gripped the attention of newspaper readers around the world. For several weeks, it garnered even more headlines than the ongoing Boer War, and in 1963 the incident was given the Hollywood treatment in 55 Days at Peking (in which a character based on Conger’s husband appears). Eventually, an Allied Army — marching behind the flags of Japan, Russia and six Western countries — freed the captives and took control of Beijing, after first ending another siege in nearby Tianjin.

On July 7, there was no way Sarah could have known how much longer families like hers would be trapped in Beijing, or that any of them would make it through the ordeal alive. The situation she describes in the letter was a dire one. She referred to part of the American Legation going up in flames, and the family’s worry that Laura’s beloved pony would need to be killed for food, as rations were running low. (It was spared, though some other horses were not so lucky.) Her letters, however, show that she expected to survive due to her deep faith. A convert to Christian Science, who occasionally corresponded with the creed’s founder Mary Baker Eddy, she believed in direct divine intervention. In the same letter, she expressed confidence that the Lord had been protecting her and other foreigners, and would continue to do so:

God’s loving hand alone saves us. When the enemy, after many attempts, gets the range to harm us, and a few shells would injure our buildings, then the hands of these Chinese seem to be stayed. … How could this be true if God did not protect us? His loving arm is round about us.

Unintentionally, Conger’s letters remind us that Chinese and foreign participants in the events of 1900 did not have entirely dissimilar beliefs. At the time, it was routine to mock the Boxers for thinking that they could protect themselves from bullets with incantations and spirit soldiers. Yet Conger was not the only foreigner in China who thought that a heavenly force was protecting her.

There was no way Sarah could have known how much longer families like hers would be trapped in Beijing, or that any of them would make it through the ordeal alive.

Who then was Sarah Pike Conger, other than a deeply religious woman married to an important envoy to the Qing court? Born in Illinois, she studied astronomy at Lombard College at a time when female students rarely focused on the sciences. Before arriving in China in 1898, she was already well-traveled for an American of her time, having lived in Brazil for several years following her husband on his previous diplomatic posting. While she is not the most famous American woman to have lived through the 1900 crisis — that distinction is shared by Pearl Buck, who would rise to fame with the publication of The Good Earth in 1931, and Lou Henry Hoover, who lived through the siege of Tianjin and later became First Lady of the United States — Conger’s name would have been a familiar one to many when her book came out.

Sarah Conger’s fame peaked during the siege of the capital, when American news reports routinely included speculations on the fate of the Conger family, and included sketches of Edwin and Sarah. Members of her faith took a special interest, as shown by a report of a curious ritual that ran in the Chicago Daily Tribune midway through the siege. “Nearly 1,000,000 Christian Scientists in this country are trying to save the life of Mrs. E.H. Conger,” proclaimed one article from July 15, titled “To Save Congers by Thought.” To protect her, the report outlined, believers had been “concentrating their minds” on her predicament, striving to use the “power of thought” to “influence by thinking” the actions of the Boxers (described as “the millions of fanatics in China”).

At the start of the siege, many people around the world were convinced that Conger, along with every other resident of the Legation Quarter, was dead. Early in July, telegraph messages carried a rumor that diplomatic families had been massacred, and newspapers ran reports of the streets of Beijing running red with the blood of foreigners. The fact that direct communication between the Legation Quarter and the outside world had been cut off for weeks gave credence to this misinformation. A mass memorial service for British martyrs was scheduled for St. Paul’s Cathedral, and a funeral for the Congers was planned in Iowa. Both were canceled when Edwin managed to get a cable out in mid-July, informing the world that the reported massacre had not happened.

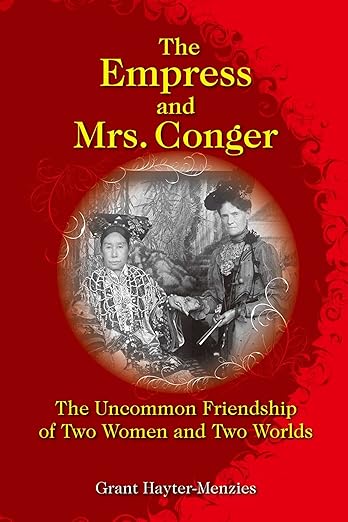

Sarah Conger’s second burst of fame came when the leading figures of the Qing government, who had fled into exile when the Allied Army took the capital, returned to their Beijing palaces early in 1902. She led the wives of diplomats in meetings with female members of the Qing court that aimed to improve relations between China’s rulers and the foreign community. Through these meetings, she formed an unlikely bond of affection with the Empress Dowager Ci Xi. This is the subject of an intriguing 2011 book, The Empress and Mrs. Conger: The Uncommon Friendship of Two Women and Two Worlds by Grant Hayter-Menzies, the cover of which shows a famous photograph of Ci Xi and Sarah Conger, their hands touching.

Telegraph messages carried a rumor that diplomatic families had been massacred, and newspapers ran reports of the streets of Beijing running red with the blood of foreigners.

Letters from China contains letters written between 1898, just after the Congers arrived in Beijing, and 1908, three years after they left China. Two sets of epistles in particular generated the most interest when the book was published. First, there were the letters conveying Sarah’s ideas about the Boxers, and her descriptions of the siege as a “reign of terror to those here and elsewhere.” Second were the letters recounting Sarah’s friendship with the Empress Dowager. Few people wrote about direct encounters with this enigmatic figure, but Conger — whose last letter in the volume is a sorrowful eulogy for Ci Xi, who died in November 1908 — was able to do just that.

In reading the book multiple times, however, I am struck most powerfully by the letters Conger wrote between the time the Allied Army took Beijing and her meeting the Empress Dowager. In these, she laments the physical toll the fighting and its aftermath took on Beijing, including the devastation of the imperial observatory, one of her favorite haunts. She also worries about the continuing human toll of the Allied response to the sieges of Beijing and Tianjin, in a poignant letter dated September 28, 1900, written to one of her nieces in America.

“Some people feel very revengeful and cry out against showing mercy to the Chinese,” Conger writes. “They say, ‘Burn every town and village!’” This disturbed her. She stressed that “the cruelty of the Chinese toward the foreigners has been extreme,” but noted that the country was filled with people who wanted only “to be left alone in their own land.” It would be tempting, she said, to adopt an “eye for an eye” approach to make up for the “awful experiences” foreigners had endured in the sieges, as well as for the Boxer murders of Western missionaries and Chinese Christians — but to give in to cries for vengeance, she claimed, would be to “sting ourselves with our own malice.” Yet, in the final months of 1900, what she feared came to pass as the Allied troops carried out brutal punitive expeditions in the surrounding countryside, killing thousands of innocent villagers and destroying their homes.

After leaving China in 1905, the Congers lived in Pasadena, California, where Edwin passed away in 1907. Sarah would go on to write a children’s book about Chinese culture, Old China and Young America, and died in 1932, in a Christian Science rest home in New Hampshire. But Letters from China was her lasting legacy, and a testament to how varied responses to human horrors can be. Many Westerners, who were never in harm’s way, called for the Allied Army to show no quarter in exacting revenge after the siege was lifted. Conger, by contrast, moved swiftly from seeing her loved ones at risk, to worrying about a new group of Chinese victims as soon as the Western ones had been freed. ∎

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is Chancellor’s Professor of History at UC Irvine, with a focus on modern China. He is the author, co-author, editor or co-editor of over a dozen books, including China in the 21st Century (2010), Vigil (2020) and the forthcoming The Milk Tea Alliance (2025). A frequent contributor to both scholarly periodicals and newspapers and magazines, he was editor of the Journal of Asian Studies (2008-2018), and co-edits the China section of the Los Angeles Review of Books.