Long before Liao Yiwu became a writer of stories, he listened to them. When he was little, growing up in Sichuan in the early sixties, his older sister Fei Fei hummed songs from old movies as she kneaded the family laundry against a washboard. Before bedtime, she told her younger siblings horror stories: a dead body wakes up in a morgue; a gruesome murder takes place in an ancient bell tower. Terrified, Liao would pull the quilt over his head.

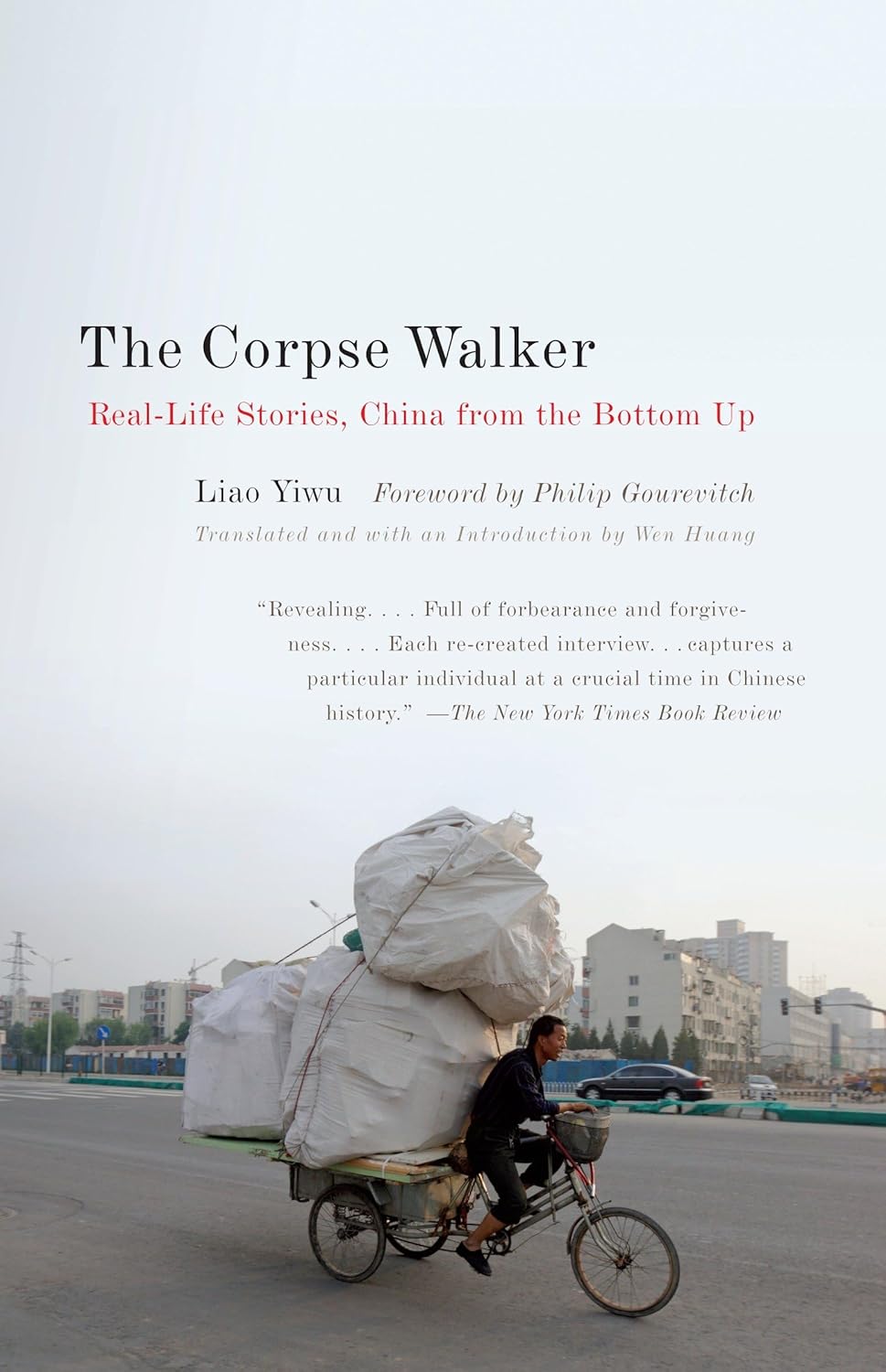

In the aughts, Liao became internationally known when the English translation of his oral histories were published in The Corpse Walker (Anchor, 2008), a collection no less unsettling than his sister’s tales. A villager lets his neighbors set his wife on fire because they believe that she is possessed by an evil spirit; a trained professional walks long distances carrying a dead body on his back so that the deceased could be buried by their family. The book was the result of Liao’s conversations with Chinese commoners between 1993 and 2006, whose way of life was disappearing as China modernized. If well-known figures are like the leaves and branches of a tree, Liao said in a 2023 speech at Stuttgart city hall, “I want to examine the sprawling roots, and write about their tears for having no hope of rising above ground one day.”

Since 2011, Liao has lived in Germany as a writer in exile, where he has been celebrated at prestigious forums and with literary awards, such as the 2012 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. He has published half a dozen books in English, on subjects from Chinese Christians to the survivors of the Tiananmen massacre. When Liao started out as a writer, however, his scene was anything but literary talks and highbrow venues.

Liao doesn’t call himself a reporter, but his early writings are often styled as interviews, which are reproductions of casual conversations he had over the years. One shouldn’t consider these pieces non-fiction in the traditional sense, where a writer shadows a source with a notebook or a voice recorder. Liao’s casual methodology — freestyle conversations followed by largely memory-based reproduction of stories — had drawn suspicion from Chinese journalists, who cast doubt on the veracity of his writing. One of them, Feng Shanshu, an investigative reporter, spotted a number of chronological inconsistencies. Another, the non-fiction writer Lu Yuegang, wrote: “I think a more capacious read of this book is to consider it literature instead of journalism.” (Liao himself has expressed admiration for Ryszard Kapuscinski, the Polish writer who blurred the line between reportage and fabulation.)

In person, Liao is a dynamic storyteller, thrilled to see his audience react — with sympathy, laughs and grimaces — to his evocative and often provocative statements. Despite his shiny pate and plain clothes, Liao would never be mistaken for a Buddhist monk given the air of stubborn insistence in his resting expression. Only when speaking, his pursed lips relent and he lets out an impish smile. Most of his anecdotes reappear over and over in his tellings and writings. He is irrepressible in these retellings, like a river rushing through familiar waterways. There is no point in trying to distinguish where the stories he writes end and the stories about him begin. He has a way of always making himself the story.

Literary critics speak of the conundrum of a writer’s second book: will it be repetition of the familiar or break new ground? This challenge has a special resonance for émigré and dissident writers abroad, when there is distance between them and their former subject matter. Liao’s early work was born out of being close to the ground, meeting ordinary people from all walks of life and absorbing the physical and emotional aspects of their worlds. This modus operandi became impossible for him once he left his homeland. But would he try to overcome this distance, or lean into it?

Liao’s early work was born out of being close to the ground, meeting ordinary people from all walks of life and absorbing the physical and emotional aspects of their worlds.

Liao Yiwu was born in Yanting county, Sichuan province, in 1958. His father taught classical Chinese at a local high school and his mother was a music instructor. When the Cultural Revolution started in 1966, Liao Sr. was denounced as a “counter-revolutionary” for being an intellectual (his own father was also once a small landlord) and his books were confiscated and burned. At struggle sessions, he was subjected to verbal and physical abuse, along with the school headmaster and other teachers. Liao’s parents divorced so that the children wouldn’t be implicated. His mother and the Liao siblings left Yanting, where they had been identified as family members of a counter-revolutionary. (The family reunited later.)

It was in those years of chaos that Liao entered adolescence. He wandered around Sichuan, hopping trains and trekking mountain trails. Liao confessed to some petty theft in his youth: once, when staying in a village, he stole a rabbit from a neighbor and kept it in a cellar full of sweet potatoes. “The rabbit grew fat and we cooked it,” he told me. (Later, when I told a friend about this story, he pointed out that raw sweet potatoes can be difficult for rabbits to digest.) After graduating high school in 1976 — the year Mao died — Liao didn’t get into a college, his wanderlust escalated, and he picked up odd jobs as a cook or truck driver.

In the 1980s, he became a self-taught poet. Liao was infatuated with the Beat Generation of American writers, who were just beginning to be translated into Chinese. “I loved their kind of purity, the spirit of fearing neither heaven nor earth,” he told me. He acutely understood that the social norms of his childhood — the Mao era — were fading and the new rules were yet to be written. Liao was an enthusiastic adopter of modes of writing and living that were the polar opposite of the world he grew up in.

In 1988, on one of Sichuan’s notoriously treacherous mountain roads, Liao’s older sister Fei Fei was traveling in a minibus that swerved off the edge. Her waist was pierced by a tree branch and she died, at 37 years old. When the telegram reached Liao, he was stunned. “How could my sister, this gentle breeze, have been mangled by the violence of a car accident?,” he wrote in a story that was later translated and published in Harpers.

In those years, Liao said, he was disinterested in politics, calling himself an “anarchist.” For many Chinese born in the fifties and sixties, political campaigns and mobilization equated to the darkest chapters of the Mao years. During the student demonstrations and political renaissance of the late 1980s, Liao was indifferent at first. In the wee hours of June 4, 1989, however, after hearing news of the killings at Tiananmen Square on live radio, Liao was shocked into action. He composed a raging poem called Massacre, which he recorded on cassette tapes for clandestine distribution:

Freedom will also come back from the dead.

It will come back to life in generation after generation.

Like that dim light just before the dawn.

No. There’s no light.

At Utopia’s core there can never be light.

Our hearts are pitch black.

Black and scalding.

Like a corpse incinerator.

In early 1990, he was arrested and sentenced to prison for four years. Liao recalled to me the ritual of prison intake. It started with head-shaving and clothes-stripping. “Then they made me stick my butt out, really high, so they could use a chopstick to inspect if I was hiding something inside,” he said, with a mixture of resentment and jest. “I was feeling vulnerable at the time. I thought I was a famous poet!” He talked about the hierarchy among his cellmates in terms of who got to use the good toilet paper. Also limited was writing paper — sheets so brittle that heavy-handed strokes would break them. Nevertheless, he began writing about the people he met in prison, producing some 200 pages that were smuggled out of prison (the result, mostly fiction, was never fully published).

After Liao was released in 1994, he was shunned from society. His wife asked for a divorce. He moved into his parents’ apartment, and hung around bars in Chengdu with his bamboo flute. Such bars were filled with lonely souls — chronic depressives ruminating on bad breakups — and by two or three in the morning, they would pay for him to play melancholy tunes. Intimate conversations in this period became some of the earliest materials for his “bottom up” writing. His time in prison stripped away his respectability, but it also conditioned him as the kind of writer he would go on to be.

Liao has said he didn’t want to become a “symbol of freedom” for outsiders. But his fixation on the David and Goliath storyline risks turning himself into exactly that.

In 1999, an unofficial bookseller helped publish a collection of Liao’s oral histories, titled Interviews with the Lower Strata of Chinese Society (中国底层访谈录), using an ISBN number purchased from China Drama Publishing House (戏剧出版社). The book sold well, Liao told me, going through four reprints in a month. But the authorities, who thought the book reflected badly on Chinese society, shut down the printing plant and the bookseller had to go into hiding. (In 2001, the book was published in Taiwan.) Later, when Liao wrote about the suicide of a bullied middle schooler for a small parenting journal, the story caused a sensation and the journal was forced to close. A well-known magazine, Southern Weekly, published a controversial profile on Liao and several editors were fired.

From 2003 to 2009, Liao lived in Yunnan province: first in Lijiang, where he opened a music bar, and later in Dali, a mountain valley known for its hippy vibes. As an author, Liao is at his best when he connects with overlooked people living in out-of-the-way settings. In 2009, for example, he got to spend time with a 102-year-old Catholic nun, Zhang Yinxian, who witnessed Catholicism’s rise and fall in a county of Yunnan province since the 1920s, which Liao records in a chapter of his 2012 book about Chinese Christians titled God is Red. During wartime, the nuns became full-time nannies because local parents, who were too poor to raise infants, often gave up their newborns in the field. After the Communists came to power, they closed her church in early 1952. “Overnight, everything was gone. Rats took over the place,” Sister Zhang told Liao. It is this ability to draw out untold stories with colorful quotidian details that gives such richness to some of his writing.

In 2011, however, Liao came to the point where he felt he needed to leave China. He had already been denied permission to leave the country a reported 17 times. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the Chinese government accelerated its crackdown on dissent, and Liao saw many of his peers detained and investigated, such as the intellectual Ran Yunfei and the democracy activist Yu Jie. “I had no intention of going back to prison,” Liao later wrote in The New York Times. “I was also unwilling to be treated as a ‘symbol of freedom’ by people outside the tall prison walls.”

Liao threw away his cellphone and ceased communications with friends and family. “I kept my plan to myself,” he writes. “I packed some clothes, my Chinese flute, a Tibetan singing bowl.” On a summer’s day, with these meager belongings and under the guidance of a smuggler, Liao walked over the border from Yunnan province into Vietnam, before boarding a westward plane. At 52 years old, he arrived in Germany — a move which apparently involved efforts from Angela Merkel — and began his life of exile in Berlin.

He wanted to “use words to build a monument to heroes,” but the main hero he is building a monument to seems to be himself.

Liao counted his blessings to me: since leaving China, he has been able to publish books in Europe, the U.S. and Taiwan. In his host country of Germany, his publisher, S. Fischer Verlage, released nine titles by him in the last decade or so. He is a lauded dissident. After years of observing others, he became the observed. And he gladly contributes to his public persona.

Ever the engaging showman, Liao likes to bring his Tibetan singing bowl and bamboo flute to events, such as a discussion at Asia Society last year where he gave a performance after his talk. He tells his awed audiences that these prized objects were with him as he walked out of his home country. Journalists frequently describe him as a “reluctant dissident” or a rebel with “a spontaneous quality.” Indeed, Liao is a quirky character — ask him for political analysis, and you’ll get a line like this, from the Asia Society event: “My ideal outcome would be for Sichuan to elect a president who’s either an alcoholic or a chef or both.”

In June, the academic press Polity released two new books by Liao: a “documentary novel” titled Wuhan about the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak; and a slim number with a mighty name, Invisible Warfare: How Does a Book Defeat an Empire?, a broad-margined, 70-page-long adaptation of his 2023 Stuttgart speech.

Invisible Warfare embodies the David and Goliath narrative that underpins much of Liao’s work. He wanted to “use words to build a monument to heroes,” but the main hero he is building a monument to seems to be himself. In this volume, Liao draws analogies between himself and Marcel Proust, Joseph Heller and Anne Frank, and compares his work to Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago and Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. If a single book can defeat an empire, as the subtitle promises, this is not the one. Instead, it builds a world where characters exist to be stunned and enlightened by its author. One of his prison mates, Liao wrote, “felt there was nothing to live for, until he unexpectedly discovered that I was writing.”

Observers are not wrong to call Liao a dissident, but such a descriptor is often a trap for critics: when the significance of one’s work lies chiefly in speaking up against repression, isn’t it hair-splitting to judge it on bookish criteria such as narrative craft, consistency and clarity? Liao’s prose finds its grounding in details beyond obvious political markers. One such memorable moment is in Bullets and Opium (Simon and Schuster, 2019), his book of interviews with survivors of the Tiananmen Square killings, now in their middle age. Among them was Li Hai, then a philosophy graduate student at Peking University. After his arrest, the clean freak found himself in a dank cell filled with “sweat, smelly feet, and urine.” One night, a sudden itch made him sit up and he scratched uncontrollably. The high-minded theorist, like the petty thieves who were his cellmates, was infested by scabies.

In recent years, Liao has been nagged by the question of how a writer creates a “sense of presence” in exile. His answer — as he notes in the back matter of his new novel — is, in short, the Internet. Wuhan is a “documentary novel” cobbled together from real-life events and the encounters of a fictional character, Ai Ding, at the outset of the Covid outbreak in China. Ai is a historian who is doing an academic program in Germany, and his annual trip to visit family in China for Chinese New Year in 2020 gets derailed while he witnesses first-hand the ridiculous restrictions and the eerie ghost towns they created.

Liao described his research process for this novel with bravado similar to accounts of his earlier material-gathering, which involved trekking in remote mountains and spending time with death row murderers. In reality, his research from exile — reading online posts and downloading them before they are scrubbed by censors — are second nature among his compatriots, who habitually resist the ephemerality of online writing by taking screenshots. Liao also includes characters based on real-life citizen journalists, such as Zhang Zhan and Chen Qiushi, who reported from Wuhan only to be disappeared into secretive and lengthy detentions.

Observers are not wrong to call Liao a dissident, but such a descriptor is often a trap for critics.

Liao has said he didn’t want to become a “symbol of freedom” for outsiders. But his fixation on the David and Goliath storyline risks turning figures like Zhang, Chen and himself into exactly that. There is no doubt of the importance of their work, and the tragedy of their sacrifice. They deserve celebration and support. They also deserve to be authentically seen and treated as ordinary human beings, in life and in literary creations. By focusing on their highlight reel through a victorious filter, Liao creates just another version of abstract flattened heroes, like socialist poster figures.

Missing from the bluster and hijinks in Liao’s writing are moments of pain, suffering, frustration and doubt: the kind of vulnerabilities that don’t make the characters less, and likely make the work more. To be able to examine such vulnerabilities, however, Liao has to shed his defensive shell. The legendary exit he created for himself — a maverick fleeing China by foot with a flute in hand — masks the traumatic severance from his homeland that he had to choose. The Internet is no magic cure. A writer’s defiance isn’t just about speaking truth to power: it’s also about being true to oneself. Only by facing one’s changing realities can he or she allow something new to be born on the page.

More than a decade ago, Liao’s move to Germany was like a Cinderella story for political refugees. Now, especially in the aftermath of the Hong Kong protests of 2019 and the White Paper Movement in 2022, the displacement of Chinese writers is becoming a much broader experience. Once severance from the motherland becomes collective, grief and hope coagulate. With the emergence of diasporic publishing and writing projects, such as the independent zine Mang Mang as well as numerous new bookstore salons, including the rebirthed Jifeng and the newly-created Feidi (“Nowhere”), one of the most urgent questions facing Chinese writers today — established or aspiring — is how to find their own voice of dissent in a globalized context. Many of them arrive in the U.S. and European countries where nativism and authoritarianism are on the rise. In this political space, is your dissent any good if it’s confined to the comfort of a familiar narrative, stripped of fresh specificity and isolated from events unfolding around you?

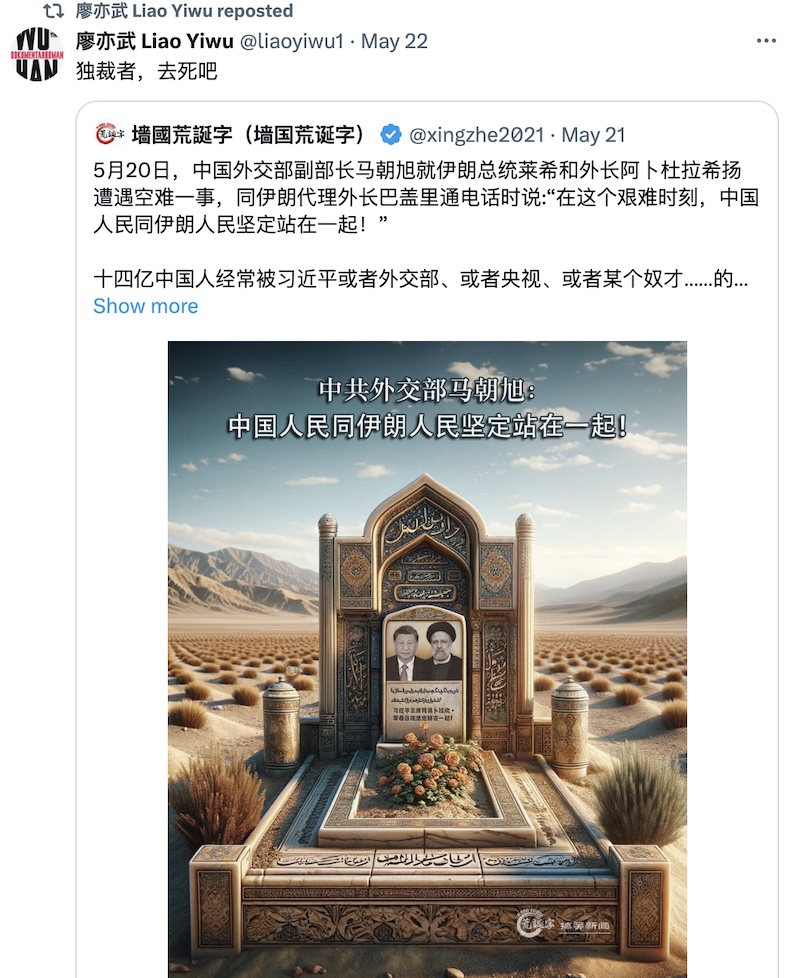

Liao is as sincere in his love for the Beats poets’ fearless, freedom-loving spirit as he is in his distaste for autocrats (“Dictators, go die,” he tweeted recently). He frequently posts admiringly of Ukraine, and expressed his support of Israel in the aftermath of the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023. Yet this spirit sometimes hits a wall: he hasn’t found any words on Israel’s subsequent bombardment of Gaza, which the medical journal Lancet estimates may have killed as many as 186,000 people. Among them, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 128 were journalists — who died trying to tell their own “bottom up” stories. In Berlin, the city that became Liao’s free-speech safe haven, pro-Palestinian protestors’ encampments were cleared by police. Who is David and who is Goliath? One person’s savior can be another group’s oppressor.

The more I learned about Liao, the more I was mesmerized by his depiction of the childhood bedtime stories he listened to with his siblings. The memories were moments of innocent comfort: pulling the quilts over his head, he was shielded from the fictional ghostly figures, safe in the presence of his beloved sister Fei Fei, and safe from the real-world horrors in futures near and far. They turned out more macabre than those tales. ∎

Header: Liao Yiwu poses during a photo session in Paris, 2019. (Lionel Bonaventure/AFP via Getty)

Han Zhang has written about the political and literary narratives that have shaped Chinese culture and identities for The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine. As editor at large at Riverhead Books, she is also working to introduce contemporary Chinese-language literature to English readers.