Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

When Xie Ding (谢丁), sitting in front of his bookstore in a residential corner of bustling Chongqing, reflected on his previous two decades in Beijing, he sounded sure of himself. “There is no need to live in Beijing anymore. The interesting people have all gone abroad or moved back to their home region,” he told me. “It’s not only the lack of public events. With the people gone, the private gatherings have also largely disappeared. Beijing has become boring.”

Conversations about Beijing’s decreasing attractiveness as a cultural hub, due to high costs and tight political management, have been getting louder since the pandemic. Reporting on the thriving independent bookstore scene in southwestern China in late 2024, I met several cultural entrepreneurs who had left the capital. Once the setting of vibrant cultural salons, Beijing continues to be home to some beautiful, well-stocked independent bookstores, but they hold few public events. “It’s too risky for them,” Chengdu-based writer Zhang Feng (张丰) told me. “One guest says something sensitive, and it jeopardizes your entire investment.”

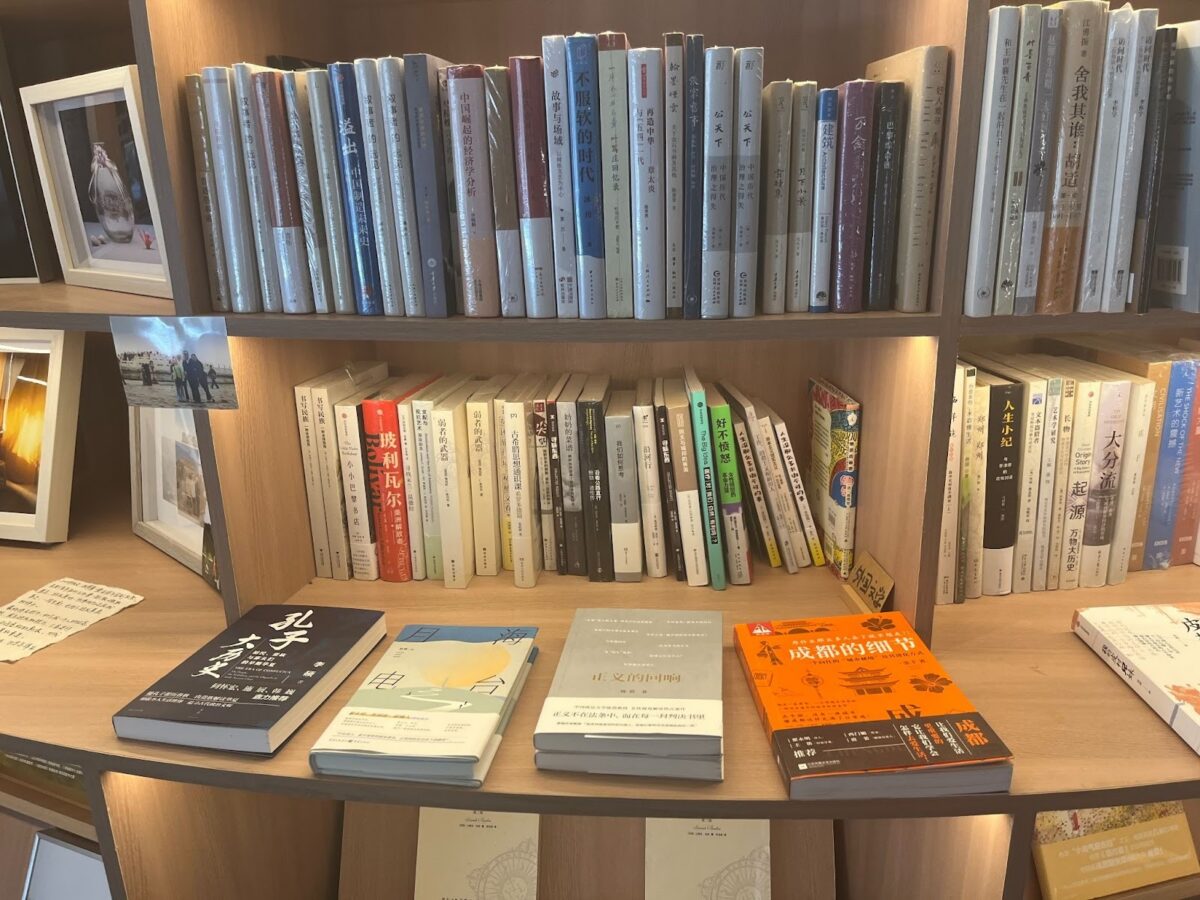

I moved back to Beijing for a role with the Dutch media in early 2024. Despite living within walking distance of several bookstores, I have only attended a couple of bookstore events since, and rarely see them advertised. In Chengdu, by contrast, you still find bookstores hosting multiple events a week. Over 20 new independent bookstores have opened their doors in the wake of the pandemic restrictions of 2020-22. While the new stores are good places to read and have coffee or a beer (most serve alcohol), the frequent events on topics of public interest, from gender and labor rights to international affairs, are what captured national attention. Despite the scene’s precarious political position, which deteriorated in the last year, it continues to stand out as a vibrant spot for public life in China.

Before my visit, media friends warned me that the scene was a bit overhyped, that the quality of the events was uneven, and that they were often attended by the same crowd. Those critiques might be true, but my own experience suggested the hype was based in reality. At each event I met people who were new to the scene. I listened along with an eager young crowd to a talk by author Hu Anyan, known for his bestseller on life as a delivery driver; a feminist book panel; and a debate on the future of the dowry tradition. I found myself both excited about all the opinions on display, and nostalgic for the time when this type of public gathering was more readily available nationwide.

So what was going on in Chengdu? And what did it signify in terms of cultural life beyond Beijing or Shanghai?

China’s independent bookstore scene revived in the 1980s, when privately owned bookstores sprouted up to sate the appetites of the reading public. The rise of “scholarly bookstores” (学术书店) in the 1990s presaged the rise of today’s independent bookstores (独立书店), as narrated in sociologist Zheng Liu’s new study Cultural Mavericks: The Business and Politics of Independent Bookselling in China (Columbia University Press, January 2026). Today, there are an estimated 500 self-declared independent bookshops in China, that distinguish themselves from state-run retailers but also from other private players through, as Zheng notes, “a stronger emphasis on cultural sophistication and moral commitment.”

In Sichuan, the recent rise of independent bookstores can be traced back to China’s Zero-Covid era, which ended in late 2022. Chengdu, the provincial capital, experienced few strict lockdowns, and the city became a magnet for people from the coastal cities getting away from the restrictions. A public lecture series organized by two former journalists in a bar called Dunbar was a pioneering success. Held outside in Chengdu’s warm weather, attendees sat on stools and camping chairs, eating takeout while listening to what was originally slated as a 100-lecture series that ran on due to public acclaim.

“It started as a way to help friends attract people to their struggling business,” explains one of the organizers, who wants to remain anonymous. “But then it gained momentum.” The organizers’ background in media helped them pull it off. “We know how to choose topics and angles, and are also very familiar with the political limits. Otherwise this would not be possible.” The talks were wide-ranging, with miniseries on themes such as history, art and sex. Protest movements, religion and China’s border areas were avoided as topics.

The series was “a breath of fresh air,” said Zhang Feng, who opened his own bookstore in 2023. A key factor enabling these store openings is Chengdu’s relatively cheap rent, lowering financial risk and starting capital. Sales from drinks sold at the events are part of some stores’ business model. “No bookstore can survive on book sales these days,” Zhang added. State-owned Xinhua bookstores face no such financial pressures.

Chengdu’s ambition to profile itself as the bookstore capital of China has also helped. A local state media platform, YOUChengdu, has supported the trend, organizing an annual Independent Bookstore Fair since 2021 — an endorsement that some booksellers say was vital to the scene’s development. After four successful editions, the bookfair was canceled at the last minute in 2025. This could be due to the fair coincidentally falling on May 17, the International Day against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia (a politically sensitive date for Chinese authorities) or it could reveal a broader change in attitude towards the bookstore scene. Whether the festival will return in 2026 remains unclear.

Theories abound about the relatively relaxed attitude of Chengdu’s government towards the scene. Perhaps it is the city’s famed teahouse culture that makes local authorities less apprehensive about public gatherings? Booksellers, readers and organizers say the tolerance reflects a local independence of mind that was also visible in how Chengdu authorities implemented Covid restrictions. Some also point to tacit support from a high-ranking city official.

Scale and media attention have been double edged swords, as state scrutiny has increased alongside them. Some stores have had to cancel events. “For several years the local government saw the bookstores primarily as a good thing,” said Zhang. But in the past two years, he has found that the procedures for registering events with the government are being followed more strictly, and police visits have become more common. The future feels uncertain. “When too many people know about something beautiful, it will become more difficult,” according to the organizer of the summer public lecture series.

The future of Chengdu’s network of independent bookstores is uncertain. But the momentum of offline community formation is more widespread.

Chengdu bookstore owners pride themselves in holding informal and relaxed events, distinct from those in Beijing or Shanghai. The bookstore settings are often cosy, and attendees are free to eat and get up. These stores attract nationally known writers and intellectuals, some of whom are unlikely to speak publicly in Beijing, but also organize community-based group discussions, or movie and game nights.

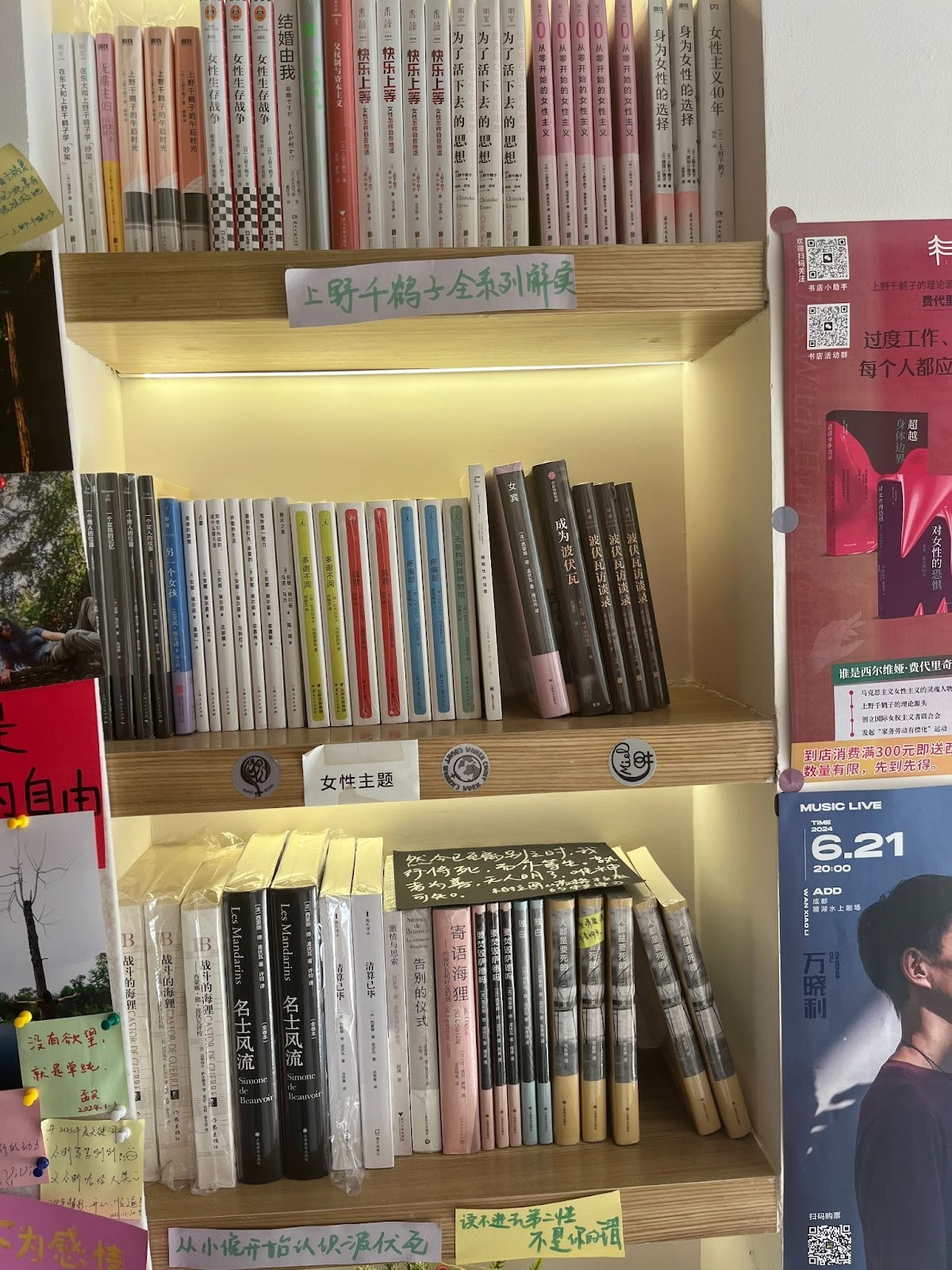

Take Laishuxia (来树下), a feminist bookstore in central Chengdu started in 2023 by Shenshen, a 40-year-old woman who left a career in real estate after she faced gender discrimination. A self-taught feminist, Shenshen has hand-picked all the books in her store, ranging from feminist classics and recent social science bestsellers to Chinese translations of Simone Weil. She says she has felt intimidated by an elitist bias in Chinese literary culture: “It can feel like you do not have a right to speak if you have not gone to Peking University.” But she found the Chengdu bookstore scene is friendly, with the small stores advertising each other’s events.

Laishuxia, literally “Come Under the Tree” in English, is named after a gingko tree that protrudes through the pavement inches from the entrance. It doubles as a community space that young women, and some men, visit regularly. “I’m here a few times a week,” said 29-year-old Xia Yu, who has made close friends in the bookshop. After returning to China from studying abroad in the UK (“where I discovered feminism”) she worked in both Beijing and Shanghai, “but I was very lonely there.”

Chinese media reports emphasize how bookstores offer a chance to “leave the internet and return to offline life.” With less room for cultural life in offline public spaces, the internet has become the main venue for public debate in China, but online “you mainly get insulted, so everyone keeps their mouths shut,” explained Xie Ding. While online anonymity used to provide leeway for speech, now offline debate in a bookstore filled with people on the same wavelength can feel safer than expressing yourself on social media, where nationalist internet users hunt people to report and private group chats are often censored.

But what is normal in Chengdu, for now, is not elsewhere. While the cultural infrastructure in regional centers, from Changsha to Kunming, is starting to catch up to their rapid population growth, in many cities the administrative culture is too rigid to let public initiatives flourish. In November 2024, the AP reported on local crackdowns on independent bookstores in Ningbo and Shanghai. It found ramped-up inspections of “illegal publications,” such as self-published books. Some stores were shuttered, and one bookstore owner was arrested on unclear charges. The report fits with a longer-term trend of independent bookstores being forced to close, including iconic institutions known for their public activities, such as the Beijing Bookworm and Jifeng bookstore in Shanghai, which later re-opened in Washington, D.C.

In 2025, the scene in Chengdu was also affected by this downward trend. At least five independent bookstores have closed since my visit, and a growing number of events have been cancelled by the authorities. Youxing, Zhang Feng’s bookstore, announced in late October that it was entering its last month of operations, but about a week later, following a public outcry, the government instructions to close the store were rescinded. Zhang immediately resumed the bookstore’s high-frequency activity schedule, and has since hosted well-known lawyers, scholars and journalists.

The future of Chengdu’s network of independent bookstores is uncertain. But the momentum of offline community formation is more widespread. As one organizer I spoke to noted, bookstores are not the only place where public life can take place at a small, politically-tolerated scale. Book clubs, “academic pubs,” urban walking tours and self-help groups all fit the bill — and can provide an encouraging dose of community amidst atomized urban life. As historian Xu Jilin put it in an interview with Chinese media, this private community formation has gained in vibrancy in the years since the pandemic.

That is how I felt at an event in Laishuxia, headlined by a divorce lawyer and a feminist scholar. After the event, the two young women I was seated between told me that they had witnessed domestic violence and misogyny growing up. “I never understood that inequality,” said one of them, Hou Mengjing, a recent psychology graduate who was visiting from Beijing because she had heard about the bookstore. She described how she would see her mother work in the fields all day only to come home and do all the housework too. “Hearing these other women makes me feel more confident about my opinion, that it is allowed to exist.” ∎

Header: Readers’ artwork tacked to the walls of Laishuxia bookstore in Chengdu. (Tabitha Speelman)

Tabitha Speelman is a freelance reporter based in Beijing. She currently works as the China correspondent for Dutch daily newspaper NRC. She holds a Ph.D. in Chinese Studies from Leiden University, and writes a personal newsletter.