Everyone loves an overheard conversation. They draw us in for their fragmentary, out-of-context nature. They fascinate us because they are not intended for us.

This quarterly round-up of recent, yet-to-be-translated Chinese titles — part of the monthly “New China Books” column alongside Alec Ash’s lists of nonfiction on China and Jack Hargreaves’ of translated Chinese literature — is a curation of overheard conversations from the world of Chinese language books. A lot has happened in Chinese publishing in the past few years: Amazon shut down its mainland Kindle ebook shop in June, and will withdraw its Kindle app next year. Publishers are clinging to social media platforms, livestreaming and video marketing with declining book sales in the economic downturn. An outpouring of fiction and nonfiction on women’s experiences has sparked a lively conversation around feminism. And a new generation of diasporic literature is in the making as Hong Kong, Taiwan and the rest of Asia grapple with their shifting relationships to Beijing.

It’s impossible to cover every nook and cranny of this vast landscape, but here are five books (with my own English title translations) that are representative of certain publishing trends emerging in China and the broader Sinophone world, and that offer a sense of what the future might look like. And because we are talking about publishing in China, the silence — what isn’t allowed to be spoken — not only matters equally, but adds to our appreciation for what can be discussed, and with such ardor and passion.

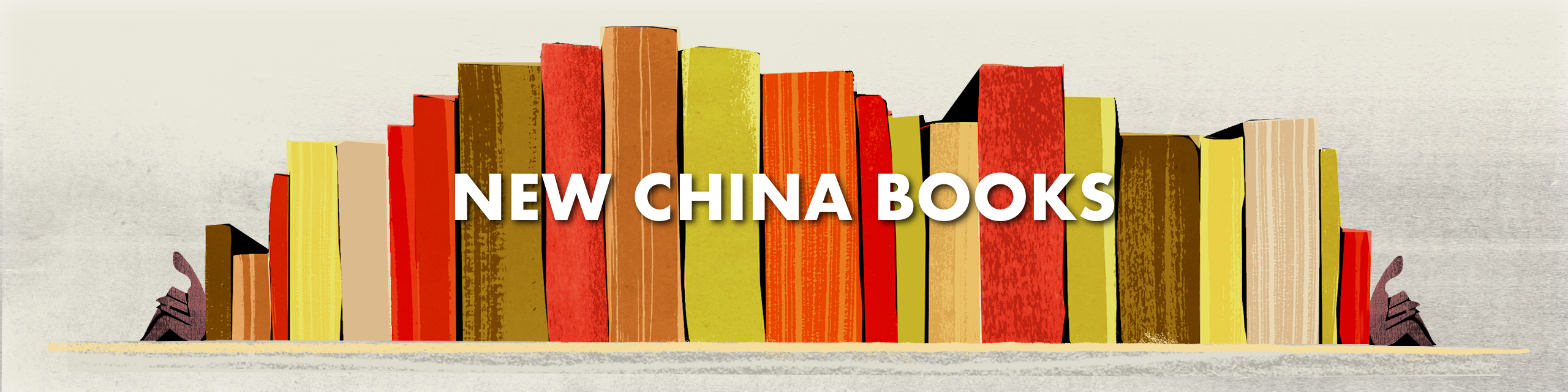

Feminism From Zero

从零开始的女性主义

The most popular author in China for the past few years isn’t Chinese. In the wake of the Chinese #MeToo movement, Chizuko Ueno, a 75-year-old Japanese feminist scholar, has seen at least 26 of her books translated into Chinese, selling more than half a million copies in the first half of 2023. Feminism from Zero is one of the best-sellers among her oeuvre, reviewed by 62,788 readers on Douban, a Goodreads-like social platform. Conducted as a series of conversations between Ueno and illustrator and writer Eiko Tabusa, it invites readers to reflect on gender expectations in East Asian societies, and teaches young women how to assert their independence and fight for their rights at work and in relationships. So far, Ueno’s “everyday feminism” has yet to hear much grumbling from the censorship machine, which makes it a relatively safe choice for publishers. And its actionable advice on everyday matters makes it an accessible guidebook for ordinary readers with little other exposure to feminism in Chinese society.

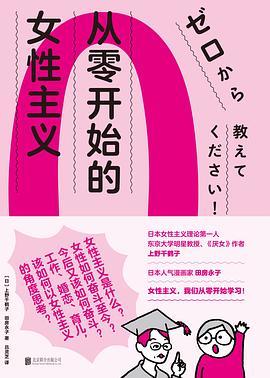

Working Class History: Everyday Acts of Resistance & Rebellion

每日工人阶级史

In 2013, Chinese artist Chen Yun launched 51 Personae, an oral history project turned publishing house, which in 2021 published the Chinese translation of Working Class History, an English handbook of grassroots movements — with a forward by Noam Chomsky — that provides “lessons and inspiration for those fighting in the present.” 372 volunteers contributed to the translation of the book, which was unofficially published without obtaining a prerequisite Cataloging in Publication (CIP) number. CIPs are strictly controlled by the state and take years to apply for; it’s unlikely that a book on this topic, or with “Resistance & Rebellion” in the subtitle, would be greenlit. In the end, it was printed clandestinely and distributed mostly by mail. Last month, the Shanghai police force confiscated all unsold copies of Working Class History and other “illegal publications” from the same publisher. Chen was sentenced to 18 months in jail and fined 60,000 yuan (around $8,400) for her own everyday act of resistance and rebellion.

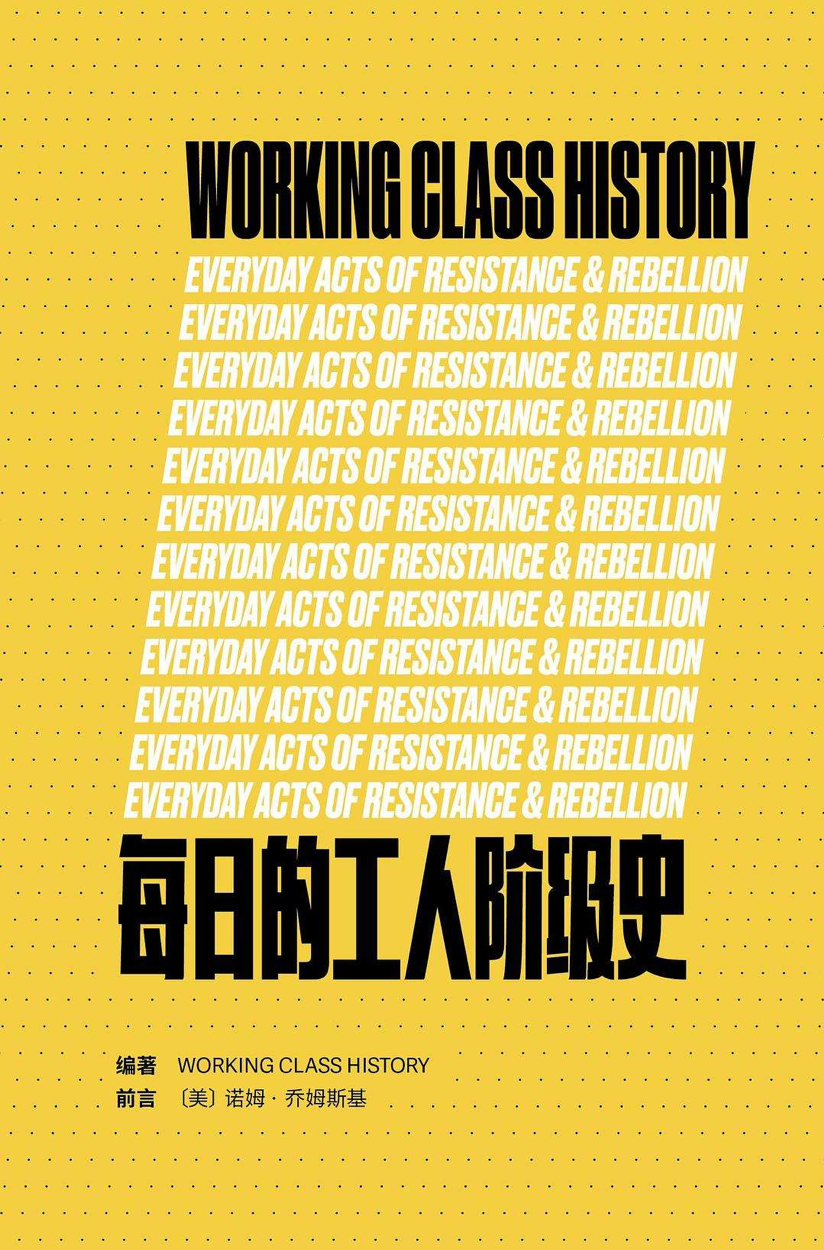

Tide Chart

潮汐图

In a pond in Guangdong province, in the 1820s, a frog gains consciousness and speaks her first sentence. She is a polyglot with an outsized curiosity about the world, and she’s a hell of a storyteller. Thus begins Chinese writer Lin Zhao’s second novel, following the enormous frog’s wild adventures from a Tanka boat on the Pearl River, to a Scottish naturalist’s grand villa in Macau, then to the London Zoo and, eventually, a retired professor’s humble home. Highly original and thoroughly researched, the novel vividly recreates a 19th-century world seized by the frenzy of imperialism, examining the vitality of multiculturalism and condemning mankind’s exploitation of nature and all creatures that call it home. Long dominated by northern voices, literature from south China has occupied the margins of contemporary Chinese writing. But as Lin remarked in an interview with me last year, “what’s on the margin lies at the center of two worlds.”

Delivering Packages in Beijing

我在北京送快递

They are everywhere. The delivery workers, speeding past us on electric mopeds. The security guards, cleaners, salespeople, convenience store staff. The smooth functioning of our modern society depends on them: their punctuality, their endurance. For half of his life, Hu Anyan worked over twenty blue-collar jobs in China, from apprentice baker to package delivery man, while nursing the dream of becoming a writer. In this autobiographical essay collection, in a voice that is unadorned and unruffled, he guides us deep into the backbone of China’s economy. We see the soul-draining red tape, the camaraderie and backstabbing among his peers, the depleting nature of working as a cog in the machine, and the occasional joy of spending a weekend on his own terms. I picked up Hu’s book with a curiosity about “them,” but finished it with a deeper understanding about us all – how our minds and bodies are chipped away by numbers, and how we endure the strain of capitalism just to be free one day.

White Portraits

白色画像

A school teacher in Taipei in the 1970s tries to stay on the safe side of political realities. A housekeeper’s employer gets into hot water having to choose between mainland China and Taiwan. A Taiwanese immigrant in Paris joins diaspora protest movements in 1968. In her latest award-winning novel, White Portraits, Taiwanese writer and translator Lai Xiangyin paints three portraits of individuals who lived through the White Terror (1947-1987), a period when Taiwanese civilians and dissenters suffered political repression under the Kuomintang government. Lai’s clean, gentle prose is full of sympathy and understanding for her characters, whose individuality remains uncrushed by the political atmosphere of their times. Politics is never presented with a capital P, but is ever-present in the background as these characters read books, write letters, snack on homemade rice cakes, gossip about their contemporaries, dance to golden oldies, and remember how a sunset sky is named in their native tongue. ∎

Hailing from Chengdu, Na Zhong is a New York-based fiction writer and literary translator. Her work has appeared in Guernica, A Public Space, Lit Hub and others. She co-founded the bilingual creative community, Accent Society, and co-hosts the Mandarin literary podcast 跳岛FM. Na is a 2021-2022 Center for Fiction Emerging Writers Fellow, and a 2023 MacDowell Fellow.