The Mao Dun Literature Prize (茅盾文学奖) is arguably the biggest book award that most people haven’t heard of. Apart from an anodyne bulletin on the English website of China Daily, coverage of last year’s winners in languages other than Chinese has been all but nonexistent.

The prize, awarded roughly every four years since 1982 to three to seven titles, has the power to transform the fate of a book. It has sealed the canonical status of works by Jia Pingwa and Wang Anyi, and this year it nudged a dense modernist brick from obscurity to bestseller, then ignited a bidding war for the film rights to an experimental espionage novel. Meanwhile, controversy over the award’s lack of transparency and its state-affiliated official patronage has doomed some of the awarded works to popular ridicule.

The five recipients of the 11th Mao Dun Prize, awarded in late 2023, vary in quality as much as topic. Liu Liangcheng’s Bomba (本巴) is the polyphonic retelling of a Mongolian epic poem. Sun Ganlu’s A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains (千里江山图) is a difficult, stylish riff on the Old Shanghai espionage novel. Dong Xi’s Resonance (回响) is a low-key domestic psychological thriller. Qiao Ye’s Baoshui Village (宝水) is a sprawling tale of rural reconstruction that, apart from being poorly written and exceedingly dull, is less subtle in its messaging than works written in the fervor of the Great Leap Forward. And Yang Zhijun’s Land of Snowy Mountains (雪山大地) is a novel set on the Tibetan plateau that is even more patronizing and ethno-nationalistic than his execrable Tibetan Mastiff series (藏獒), a much criticized dramatization-with-animals of Chinese ethnic politics.

These books will likely remain obscure outside of the Sinosphere, yet they represent big modernist or realist novels by Chinese writers firmly within the literary system, who have been isolated from the demands of a market increasingly geared toward genre and mass-market fiction. Titles that win the award have a slightly better chance of being translated into English in a competitive foreign literature market, but most are not. Even if its name routinely appears in promotional copy for these books (“WINNER OF THE MAO DUN PRIZE!”) the award is not much better known abroad than are its recipients.

There are other literary awards in China, including the Lu Xun Prize (鲁迅文学奖), which has been granted every three years since 1995 to short fiction, literary essays, poetry and reportage, and the Shi Nai’an prize, which is awarded to innovative novels (it has gone in the past to Yan Lianke, Dong Xi and Yu Hua), but the Mao Dun Prize is the oldest extant mainland award, widely cited as the most prestigious, and comes with a check worth 500,000 RMB (about $70,000). So, what exactly is the Mao Dun Literature Prize, and is it worth knowing about?

Controversy over the award’s lack of transparency and its state-affiliated official patronage has doomed some of the awarded works to popular ridicule.

The award is named after the man who founded it. Mao Dun (茅盾, homophonous with the characters for “contradiction” 矛盾) is the pen name of Shen Dehong (沈德鸿), born 1896, a writer, translator and literary revolutionary who was present at the birth of modern Chinese literature, and one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party. Alongside writers like Lu Xun and Yu Dafu, his writing tossed off the weight of thousands of years of Chinese literary tradition; instead it was aggressively modern, realist and socially engaged. Mao Dun’s reputation as a leftist writer allowed him to take up posts within the Communist Party’s literary bureaucracy after they came to power in 1949, and his major works — Rainbow and Midnight — became part of the new canon. But he was effectively sidelined from the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 to the political thaw that followed the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1978.

It was in the late 1970s that Mao Dun planned the award, which would finally be awarded in 1982, almost exactly a year after his death in March 1981, at the age of 85. The prize was funded with 250,000 yuan from his estate; 5000 yuan went to each of the first six winners. Mao Dun’s intention and hope was that the award might keep lit a flame ignited at the end of the Cultural Revolution, when the Party signaled they would give looser rein to writers and artists.

When Mao Dun died, he left his prize in the hands of the China Writers Association (CWA, 中国作家协会 or 作会 for short). This official body — a branch of the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles (中国文联), subordinate to the Publicity Department of the Communist Party (中宣部) — has ruled Chinese letters since it was established in 1949. Modeled on the long-defunct Union of Soviet Writers, the CWA might seem like a relic from another time, and its importance has declined with the expansion of new media and digital platforms. But to be taken seriously as a writer in China — to win prizes, and to secure connections within the literary community and to government, as well as sinecures and pensions — there is no escaping this cultural bureaucracy.

The choices the CWA made for the early winners of the Mao Dun Prize were not particularly controversial. Their choices reflected the trends of the times. The first batch of six books awarded the prize in 1982 was heavy on “scar literature” (a term coined by Chinese writers in the wake of Lu Xinhua’s 1978 short story “Scar” 伤痕, later picked up by Western sinologists to describe memoirs about the Cultural Revolution), with books such as Gu Hua’s 1981 novel A Small Town Called Hibiscus (芙蓉鎮) reflecting on the hardships of the previous decade. Judges for the second award in 1985 — the regularity of the prize was inconsistent in its early years — selected novels that commemorated the atmosphere of the Reform and Opening era, such as Liu Xinwu’s The Wedding Party (recently translated by Jeremy Tiang) about a backstreets Beijing wedding. The third award, given in 1991 but covering books published in the late 1980s, tended toward historical epics with local flavor, including Huo Da’s Funeral of a Muslim (穆斯林的葬礼), a multi-generational family saga of Hui Muslim jade carvers.

In these early years of the Mao Dun Prize, the reform era was still finding its feet. China’s intellectual atmosphere was thawing, but the market had not yet arrived. Outside of works published by CWA members, there were few reading choices — underground poetry journals, mostly, and writing published by Chinese writers overseas. A range of popular writing, including martial arts adventures, urban sleaze, romance and science-fiction may have already been outselling “pure literature” (纯文学) as it was called, but sales were not tracked as it was not published officially, no different to any other products hawked from the stalls and rugs of streetside entrepreneurs. But as marketization penetrated deeper, state publishers, suddenly required to turn a profit, began marketing even “pure literature” as a commodity. And some authors began converting their literary prowess into personal fortunes.

The novelist Wang Shuo, who became notorious in the 1980s for his brand of “hooligan literature” (流氓文学), took pains to point out that he was not a member of the CWA. Rather than making his bones in CWA-controlled literary magazines, or using connections to angle for prizes, he built his reputation as “China’s Kerouac” with what The New York Times called a “Madonna-style talent for marketing,” never turning down a chance to appear on chat shows, pose for a photograph, or blast his rivals in newspaper interviews. On top of his literary fiction, he made a modest fortune writing for TV and film. Wang also made headlines in 1992 when, realizing that he was being shortchanged taking the industry-standard one-time manuscript fee, he negotiated a deal for royalties on one of his best-selling novels, transforming himself almost overnight into a millionaire.

The following year, Jia Pingwa became the next writer to make headlines — again without the clear support of the CWA or the rest of the literary establishment. His 1993 novel Ruined City, a frothy, funny, sexy book, sold over a million copies despite its dense language (and, after it was banned for its raunchy obscenity, continued to sell in the form of bootleg copies). The market had overruled the CWA, delivering money and fame to these writers who defied the bureaucracy.

In response, the Mao Dun Prize ignored anything apparently tainted by the market. Judges for the 1997 Mao Dun Prize (covering books published from 1989 to 1994) snubbed younger writers who had made a dent in the marketplace. The fact that Mao Dun Prize-winner Chen Zhongshi’s White Deer Plain (白鹿原) topped sales lists in 1993 was excusable: it was the sort of sweeping modern historical epic that the CWA preferred, but Chen Zhongshi was an unimpeachably brilliant writer. Other entries from the 1990s were, if brilliant, certainly not commercial sure-shots: before the Mao Dun was awarded to them, the public was not rushing out to buy People and War (战争和人) by Wang Huo, a trilogy about the Second Sino-Japanese War with the Nanjing Massacre as its climax, or Liu Yumin’s Turbulent Autumn (骚动之秋), an artful record of Reform and Opening.

In the 2000s, the Mao Dun Prize stumbled into its third decade, moving further away from both popular and contemporary critical taste. Not only did jurors look with suspicion on commercially successful work, they also appeared to make their choices according to an increasingly obsolete definition of “pure literature,” which favored realism and epic scale over formal innovation, linguistic playfulness and narrative innovation.

The CWA is an institutional relic, but, as a bulwark against the market, it safeguards a certain type of national intelligence.

Precisely because nobody seemed to agree with the jurors, the announcement of the Mao Dun Prize longlist became a media event, with second-guessing and mockery from the commentariat. This heated up with the sixth award (covering books published from 1999-2002), announced in 2005, when febrile debate over the 23 books on the longlist spilled from literary magazines and bulletin boards into mainstream web portals including Tianya and Netease. Through the 2000s, charges were levied against the jurors that they were hopelessly devoted to realism, afraid to include novels about contemporary issues, and fearful of formal experiments.

Many also pointed out that the CWA was more likely to give the prize to ranking members in their own bureaucratic body (this was energetically refuted). The old boys’ club of the literary bureaucracy was still in control. And despite the outsized contribution of women to post-Reform Era literature, it is a boys’ club: of the 54 authors awarded the Mao Dun Prize, only eight have been women.

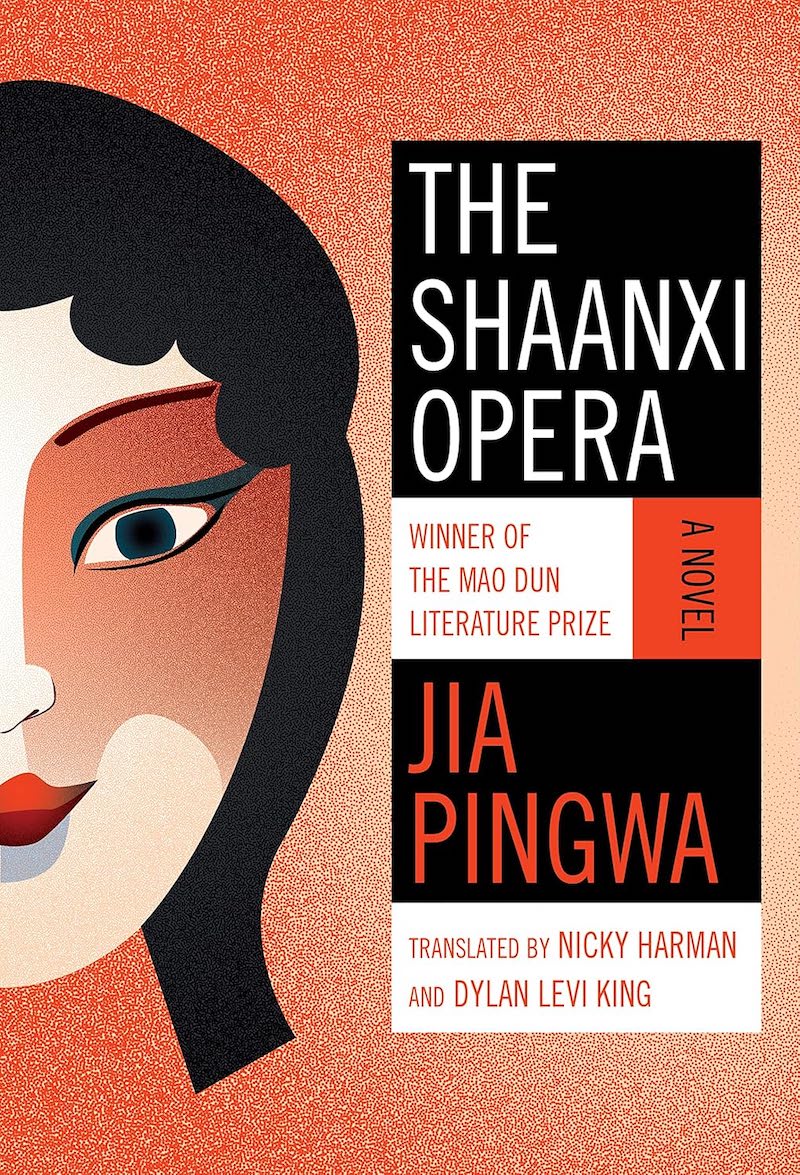

After the controversy in 2005, in the subsequent five rounds of the Mao Dun Prize up to last year’s award, the CWA gave ground to the criticism. They allowed some worthy commercial hits to make the list: Mai Jia’s In the Dark (暗算), a commercially-successful espionage novel, won the prize in 2011. They tolerated some political risk: the award going to Jia Pingwa’s The Shaanxi Opera in 2008 guaranteed his return to respectability, and helped get Ruined City off the blacklist. They bent to include the milder end of experimental fiction, with Xu Zechen being nominated in 2015 and winning in 2019 for Northward (北上). And a woman, the author Tie Ning, has led the CWA since 2006 (as well as serving on the 18th CCP Central Committee).

However, the CWA still keeps out the actual renegades, and shies away from blockbusters, tending to award establishment writers. Allegorical or historical work on social issues is tolerated, but books that address ongoing social problems are passed over, as are many vibrant works of literature in modern China, ranging from New Left subaltern writers (Cao Zhenglu, You Fengwei) to postsocialist Northeastern millennials (such as Yang Zhihan, whose gritty work on the Northeast, such as A Solid Block of Ice 一团坚冰, has so far not been nominated for a Mao Dun). Women writers are more plentiful in the long list for each round, but are still not much more likely to take a win.

While the Mao Dun Prize’s mild progressivism has ended much of the controversy over its choices, it hasn’t kept pace with competitors. The Lu Xun Prize invariably gets around first to younger writers, especially given their outstanding short fiction award, which is picked from the vital ecosystem of Chinese literary magazines. The Dream of the Red Chamber Award (红楼梦奖), presented by Hong Kong Baptist University since 2006, is a tad more adventurous. The new Blancpain-Imaginist Literary Prize, funded by a Swiss watch company and overseen by editors attached to the country’s most forward-thinking publisher, picks more young writers, and also includes story collections, the form in which the best young Chinese writers are working. Even the best-of lists on the book discussion portal Douban are a better snapshot of recent popular fiction.

Of the 54 authors awarded the Mao Dun Prize, only eight have been women.

Yet the fact that the Mao Dun Prize is in danger of obsolescence is precisely why it is worth protecting. The expansion of the free market and new media has given cash and space to a wide range of writers, but it seems worthwhile to preserve what digital platforms and an IP-churning streaming industry cannot — namely, the sort of literary fiction that is quickly going extinct. It is important to consider that a Mao Dun Prize can push sales into the hundreds of thousands or millions. The CWA is an institutional relic, but, as a bulwark against the market, it safeguards a certain type of national intelligence.

Amid the vagaries of a frivolous market, in an age of decreasing readership, to write the typical “Mao Dun Prize novel” — historically-engaged realist books, epic in scope and ambitious in scale — has become unfashionable and increasingly unmarketable. But it is no easy feat to write and publish a Mao Dun Prize-worthy work. These are increasingly rare books in a market that favors breezy memoirs, blockbuster genre-fiction and foreign translations — a market in which these more old-fashioned titles might not otherwise survive.

The Mao Dun Prize’s obscurity in the English-speaking world makes sense. After all, it is not as if many of us follow the Akutagawa Prize, the Cervantes Prize or the Prix Femina. But for those curious about Chinese letters, it would be unwise to write it off. As controversial as the award has been, and as much of a relic as it can appear, one has to wonder what Chinese literature would look like without it. It deserves more than a bulletin on the website of China Daily, at least. ∎

Header: 2023 Mao Dun Literary Prize winner Qiao Ye appears at a book festival in Xinxiang, Henan province. (CFOTO/Future Publishing/Getty)

Dylan Levi King is a writer and translator. He has written for The Baffler, Palladium and World of Chinese. He is the translator, most recently, of The Colonel and the Eunuch by Mai Jia (Apollo, 2024) and, with Nicky Harman, The Shaanxi Opera by Jia Pingwa (Amazon Crossing, 2023).