Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed:

• Alexander Pantsov, Victorious in Defeat: The Life and Times of Chiang Kai-shek (Yale University Press, 2023)

• Parks M. Coble The Collapse of Nationalist China: How Chiang Kai-shek Lost China’s Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 2023)

Earlier this year, while all eyes were on alleged Chinese spy balloons and their trajectories, another border crossing attracted more muted attention. Ma Ying-jeou, who served as president of the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan from 2008 to 2016, visited the mainland People’s Republic of China (PRC) in late March 2023, paying respects at the tombs of his ancestors in Hunan province. The visit was billed as personal, with no scheduled meeting with any major Chinese leader. Yet it was also a veiled attempt to find an alternative way through the increasingly alarming scenario of a confrontation between the PRC and Taiwan in the near future.

In January 2024, Taiwan will hold what is perhaps the most contentious presidential election in its short democratic history. Who wins between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) candidate, Lai Ching-te, the opposition Kuomintang (KMT) leader, Hou Yu-ih, or the increasingly popular third-party leader, Ko Wen-je, may have a profound effect on the question of peace or war in Asia and the world. Allowing Ma into the mainland shows that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is willing to talk to him and, by extension, the KMT. Conversely, the US allowing current Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen to visit America at the same time as Ma’s trip was a signal of Washington’s continued support for the unrecognized state.

Behind these two recent leaders of Taiwan lies the shadow of a man who was once one of the most recognizable figures in global politics: the former president of China, Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang ruled the Republic of China on the mainland, or at least substantial parts of it, from 1928 to 1949. His Nationalist (KMT) party tolerated little dissent, but played an important role in the flawed but substantial modernization undertaken in China during the 1930s, before his grip on power began to loosen.

This trajectory was shaped by two key opponents. One was the emergent CCP, forced into retreat on the Long March after Chiang’s forces acted against its members. Another was the Japanese, who made increasingly aggressive moves against China before launching a full-scale invasion in 1937, after which Chiang had to work with his former Communist opponents during the Sino-Japanese war. In part because of Chiang’s alliance with the U.S. and Britain, China won its war against Japan. But the Nationalist regime became increasingly corrupt and incompetent, reducing its credibility as the CCP launched a civil war against him in 1946. Chiang’s efforts to hold the mainland failed, and in 1949 he fled to the island of Taiwan along with millions of refugees, among them soldiers, officials and business people. He ruled over a rump state on Taiwan from 1949 until his death in 1975, and never saw the mainland again.

Chiang’s reputation has fluctuated over the decades. During the Cold War, he was a highly divisive figure. Chiang ruled Taiwan as a dictator, carrying out brutal repression of pro-democracy opposition, purging figures such as the editors of the liberal Formosa magazine, though he did allow a form of protected capitalist economy to develop. Until 1979, the U.S. continued to recognize his Taipei regime as the rightful government of China. Yet by the 1970s, Chiang’s regime began to be regarded as a nasty anachronism. A book published in 1970 by the American historian Barbara Tuchman, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, chronicled the U.S. wartime general Joseph Stilwell’s despair over what he saw as Chiang’s corrupt incompetence. And Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China that laid the path for restoration of Sino-U.S. relations marked, in Chiang’s eyes, a betrayal of the cause.

After Chiang’s death in 1975, Taiwan turned slowly but clearly toward democracy, a process tolerated by the Generalissimo’s son Chiang Ching-kuo, who ruled the island from 1978 to 1988. In 1979 the U.S. officially recognized Beijing over Taipei as the seat of China’s government. Taiwan increasingly seemed to be a historical backwater, a Cold War anomaly — as did Chiang Kai-shek. The late 1970s were a low point for his reputation: forgotten in the U.S., despised by Taiwan’s increasingly democratic public and reviled as a loser in the Chinese mainland.

Chiang ruled Taiwan as a dictator, carrying out brutal repression of pro-democracy opposition, though he did allow a form of protected capitalist economy to develop.

The next two decades saw a remarkable shift in perceptions of Chiang. His reputation remained low in Taiwan, where calls for his legacy to be revised or rejected grew increasingly strong. But ironically, even as his reputation shrank on the island he had ruled for so long, it began to grow in China and the West. In the more liberal 1980s, Chinese historians reassessed Chiang and his regime, pointing out that despite his flaws, he had been a consistent opponent of the Japanese. Western scholars, notably the Cambridge historian Hans van de Ven, also gave a positive, revisionist view of Chiang as a military commander, showing that many of the wartime decisions he took were rational and not, as previously portrayed by his opponents, foolish or passive. Van de Ven’s 2017 book China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China argues that Chiang’s record should be understood as that of a commander keen to modernize his troops and make them more effective.

Between 2006 and 2008, the Hoover Institution at Stanford made Chiang’s diaries, stretching from the 1920s to the 1950s, open to scholars. Major Sinophone historians, such as Yang Tianshi from China and Lu Fang-shang from Taiwan, wrote significant studies of his leadership based on those materials. Chiang had been neglected by Anglophone biographers, but in 2003 the British journalist Jonathan Fenby wrote Generalissimo, a study depicting Chiang in negative but not strident terms, using mainly English sources. In 2009 the American writer and former diplomat Jay Taylor used the diaries to write a longer biography of Chiang, confusingly titled The Generalissimo, which was a much more positive assessment drawing extensively on Chiang’s own words.

The interest in Chiang Kai-shek continues. Alexander Pantsov, a historian at Capital University in Ohio, is an indefatigable chronicler of the lives of 20th century China’s biggest political figures, with jointly-authored biographies of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping to his credit. His new biography, Victorious in Defeat: The Life and Times of Chiang Kai-shek (Yale University Press, March 2023), provides a soup-to-nuts account of Chiang’s life, composed in Russian and then translated into crisp English prose by Steven Levine.

The implication of Pantsov’s title is that mainland China today is the sort of market authoritarian state that Chiang would have favored. The book is a fair-minded and sensible account of Chiang, and a work of impressive scholarship using Chinese, Russian and English sources with skill. The Russian archival material — his access is unlikely to be replicated anytime soon, given the current war — doesn’t overturn historians’ view of the period, but adds fascinating new details. For example, accounts from Soviet advisers sent to China in the 1920s show just how badly they underestimated Chiang’s suspicion of them, and his willingness to purge leftist allies to take control of the nationalist Chinese revolution of 1926-8.

Pantsov’s biography is sympathetic to Chiang, and although he is critical of many of his decisions, he regards him as a man who was faced with unenviable choices and made the best of them. He gives Chiang credit for the almost impossible task of trying to deal with Stalin from a position of relative weakness, and for his general ability to navigate between the great powers. Above all, he takes him seriously as a genuine, if flawed, nationalist, whose enthusiasm to end foreign influence in China was never in doubt.

The implication of Pantsov’s title is that mainland China today is the sort of market authoritarian state that Chiang Kai-shek would have favored.

Another account of the Generalissimo, published at the same time, is less positive. Parks M. Coble, a scholar at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, uses the lens of an economic historian rather than a biographer in The Collapse of Nationalist China: How Chiang Kai-shek Lost China’s Civil War (Cambridge University Press, March 2023) to assess Chiang’s downfall on the mainland. Coble is sensitive to the poverty and turmoil racking China during the civil war, which would have made life difficult for any ruler. Yet his deep research shows the danger that comes from warring elites within government: top leaders vie with each other as the economy collapses.

The spine of the story here is about money, and how the loss of its value destroyed a society. We follow vain attempts by Chiang’s ministers to halt galloping inflation as living standards and morale plummeted and costs soared. Thanks in part to these economic factors, the civil war went from winnable to irrecoverable. Chiang himself is more of an offstage figure, as he knew little about the economy. Instead, we meet the various members of his family who were interwoven with the government. One brother-in-law, finance minister H.H. Kung, is simply venal, whereas another, former foreign minister T.V. Soong, comes across as a relative liberal constrained by a collapsing system.

Coble’s account is a devastating deconstruction of the Nationalists’ economic policy, and suggests that venality and incompetence made a toxic combination from which Chiang’s China never recovered. Coble shows in rigorous detail that Chiang’s government repeatedly allowed the printing of money that sent inflation out of control, combined with corruption and a lack of willingness to rein in spending on the military. The book is a more specialist read than Pantsov’s, but it is compelling in its detail on how Chiang’s regime chose not to control the supply of money, ending up with a worthless currency that undermined military efficiency and civilian morale.

Coble’s deep research shows the danger that comes from warring elites within government: top leaders vie with each other as the economy collapses.

Can we apply any conclusions from Chiang’s achievements and failures to present day China? There are few economic parallels. China is currently suffering from deflation and has not had hyperinflation since the 1940s (although prices did rise alarmingly in 1989, leading in part to the protests of that year). And the politics of both Taiwan and mainland China have moved on since his rule. Instead, it is more worthwhile to assess Chiang’s reputation today, and to examine what that tells us about cross-Strait relations.

There’s no doubt that the ability of Taiwan to regenerate itself as a democratic state has been attractive to the wider Chinese diaspora. A 2023 Pew survey of Chinese-Americans shows that 61 percent of them regard Taiwan favorably, while only 41 percent regard mainland China positively.

Yet in Taiwan itself, there have been more ambivalent findings on Chiang’s legacy. Starting in the early 21st century, several hundred statues of the Generalissimo were taken down or relocated to the garden near his mausoleum. Three years ago, the consulting firm Redfield and Wilton surveyed Taiwanese on what they thought of Chiang: 43 percent considered him to be a dictator, and 38 percent were “ambivalent.” In the same survey, however, 50 percent of those who had voted for the KMT candidate in the 2020 election regarded Chiang positively — though the democratic endpoint for Taiwan may have softened their views.

Chiang Kai-shek’s reputation on the mainland has also fluctuated. In his hometown of Xikou, his old home is preserved for visitors, and there are biographies of him published in mainland China that are positive about his wartime contribution. In the 2010s, it was common to find actors cosplaying Chiang — complete with shaven head and black scholar’s robe — outside Nationalist Party monuments such as the old presidential palace in Nanjing, or Chiang’s wartime headquarters at Huangshan, outside Chonging. Selfies were encouraged. But the Nationalist period remains sensitive in other aspects, in order to preserve the narrative that the Communist Party saved China in 1949, even though his wartime actions have been more favourably treated in twenty-first century textbooks.

In a 2020 survey, 43 percent of Taiwanese considered Chiang Kai-shek to be a dictator … yet 50 percent of those who had voted for the KMT candidate in the 2020 election regarded Chiang positively.

One of Chiang’s strengths was that, for many decades, he managed to govern a faction-divided ruling party during a period of immense turbulence. There was never any doubt that Chiang’s Nationalist Party was authoritarian. Its security chief Dai Li was not known as “China’s Himmler” for nothing. Yet there were also figures, such as T.V. Soong or foreign minister Wang Shijie, who could envision a more constitutional future. There was also a range of genuinely liberal figures who never joined the Party but were willing to tie themselves to the Nationalist project, such as the scholar and diplomat Hu Shi.

Chiang’s attitude toward liberal dissent was mercurial. It might get you killed, as with the poet Wen Yiduo who spoke out against the government’s authoritarianism and was gunned down by Nationalist agents in 1946 (although some historians argue Chiang did not know about the killing in advance). Or it might get you hired, as with the historian Jiang Tingfu, who wrote powerful critiques of Chiang’s dictatorship in journals such as Duli Pinglun, but who was made Chiang’s ambassador to the USSR in 1936, and to the UN a decade later. It was never entirely clear why some figures found favor while others were persecuted. Some of it must have been a pragmatic calculation about who could be useful for a particular task, but Chiang also had a longstanding belief that people could be converted to his view — an idea perhaps shaped by Confucianism and Christianity, two thought systems that sustained him.

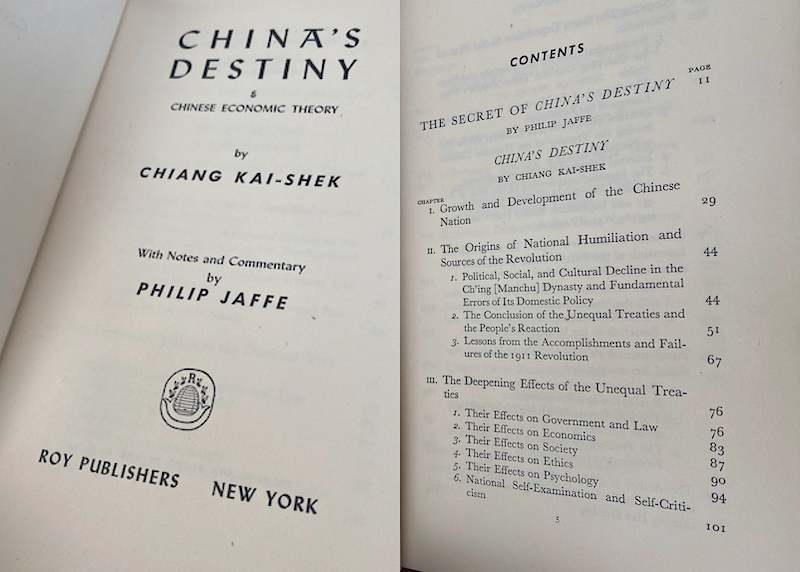

However, it would be a mistake to say that Chiang should be considered ideologically vacuous, or that his regime did not have a clear guiding philosophy. It is worth remembering that Chiang’s devotion to the Nationalist cause in the late Qing and early Republican years was enthusiastic: he was angry at China’s diminished status in the world and was determined to remedy it. Yet Chiang never had a fully formed ideology of his own, and attempts to create one — such as in his 1943 book China’s Destiny, partly ghost-written by the conservative journalist Tao Xisheng — did not meet with much approval. Though it tried to draw on the Three Principles of the People of Sun Yat-sen, the Nationalist leader whose mantle Chiang had inherited, the book was a mish-mash of resentful-sounding nationalism and protectionist economics, condemned by critics such as the Communist theorist Chen Boda as “fascism.”

As noted in one of the most interesting accounts of Nationalist thought during China’s Republican period of 1912-49, Brian Tsui’s 2018 book China’s Conservative Revolution, there was also an active and highly contested range of views within the Nationalist Party’s right wing, ranging from explicit fascism to conservative authoritarians who might sit in the same ideological spot as Spanish authoritarian leader Francisco Franco or Austrian right-wing politician Engelbert Dollfuss. Chiang alone did not define the thought system of the Nationalist Party. Instead, he showed considerable skill in keeping an ideologically big tent together, usually siding with the authoritarians but giving some liberals just enough encouragement to keep them on board (as in the debates in 1946 over a new constitution, which briefly seemed to promise a more pluralist future for China).

In his use of terror, Chiang Kai-shek seems in some ways more similar to Vladimir Putin than to any major Chinese Communist leader. Chiang’s highly authoritarian government, which nevertheless kept some vestiges of civil society, led to the frictions at the edges of Chinese society that were harder to find in Stalinist Russia or the Mao era. In those models society regulated its own behaviour, constrained by the idea of constant surveillance. Though Nationalist figures such as the security chief Dai Li may have wanted to run such an Orwellian society in 1930s China, it would have been impossible; they never held a sufficient level of control over the country. Instead, their capacity to inflict sudden terror served to cow their opponents. Putin, likewise, even during the earlier years of his rule when Russia still had some civil society, turned regularly to the assassination of opponents. China since 1949, and certainly since 1978, has used arrest and imprisonment but rarely assassination as a tool to bring dissidence under control. It is ironic that both Chiang and Putin, who might be considered authoritarian conservatives, both drew on such classic Leninist tactics.

In his use of terror, Chiang Kai-shek seems in some ways more similar to Vladimir Putin than to any Chinese Communist leader.

Mao wrote at length about “contradiction” as a Marxist idea. Chiang, no Marxist himself, embodied it — not least in his dealings with the USSR, then the world’s only Marxist state. At home Chiang was ruthless in his anti-communism, forcing the CCP on the run in the Long March of 1934-35. Yet overseas, he was driven largely by Realpolitik, and spent much time and effort negotiating with Stalin. To some extent he had little choice, as his son Chiang Ching-kuo spent much of the 1930s in the USSR as a “guest” of the state, even marrying a Russian. Yet there was a clear strategy in mind: to string the USSR along.

Chiang was a fervent anti-imperialist, and had cold relations with British leaders. He was also frequently angry with the Americans, particularly during his falling-out with Joseph Stilwell during World War II. Yet Chiang’s diaries (which Coble also drew on for his book) show that he saw an alliance with the U.S. after the war as the best choice for China — and that cutting a deal for neutrality with the USSR was therefore imperative. Several days of hard negotiation by Chiang’s diplomats in Moscow in summer 1945, interrupted by the first atomic bomb, led to a Sino-Soviet agreement that year. The purpose of this was not to create a real alliance, but rather to neutralize Soviet influence in China and enable Chiang to deal with the CCP without interference. The tactic did not work, as the USSR began to assist the CCP again from 1946. But it was an example of a technique that, in different forms, is still used today by China: creating partnerships on all sides to ward off the prospect of being surrounded.

The problems that Chiang Kai-shek faced in the 1940s were immeasurably different from those that China faces today. But the challenge of balancing competing goals — economic recovery with a nationalistic, irredentist project for total control — has echoes in China’s present day situation. Pantsov’s title, Victorious in Defeat, sums up some of the dilemma. Today’s China — essentially Deng Xiaoping’s promotion of market socialism with globalized characteristics — is not that far from what Chiang (or the more liberal forces within his cabinet) might have wanted China to become. The Nationalist version of tariff policy and corporatist economics was similar in many ways to Beijing’s policies today.

Also like Chiang’s early leadership of China, today Chinese growth and security is dependent on avoiding a major confrontation. Chiang had little control over the influence of the USSR and Japan, let alone that of the West. As Pantsov points out, “until his move to Taiwan he rarely had a single day of peace.” Chinese leaders today are lucky that their country sits in a relatively peaceful and prosperous region. They have agency over whether it remains that way: a choice that Chiang, who lived through both hot and cold wars, would have envied. ∎

Rana Mitter is a historian of modern China. He is ST Lee Chair in US-Asia Relations at the Harvard Kennedy School, and previously was Professor of the History and Politics of Modern China at Oxford University. He is the author of multiple books on 20th century Chinese history, most recently China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism (2020).