There is a joke that illustrates the restrictions imposed on storytellers in China: “No supernatural beings are allowed to take form after the founding of the People’s Republic (建国之后不许成精).” Despite its rich tradition of myths, legends and folklore, the atheist communist state shuns religious expression, suppressing any form of worship or display of superstitious beliefs. Censorship casts such a wide net that not even immortals and ghosts are exempt. When the present is a minefield of taboo subjects, the past becomes relatively safer ground for storytelling.

The last decade has marked a golden era for period dramas on Chinese television, including hits such as Empresses in the Palace (甄嬛传) and Nirvana in Fire (琅琊榜), both set in fictionalized dynasties. This trend has been accompanied by a surge of historical works, both fiction and nonfiction, published in the past ten years. In China, the tradition of “criticizing the present by alluding to the past” (借古讽今) is almost as old as the nation’s history itself. As the state tightens its control over current narratives, historical writing serves a multifaceted role: a place to escape to; a national identity to reckon with; and a mirror to reflect the reality we live in.

In the latest edition of this quarterly column of untranslated Chinese titles, we select five recent books that look as far back as the beginning of Chinese civilization, and as close as the decades leading up to its communist rebirth. Through their rigorous re-imaginings of the past, each speaks to the present in their own special way:

Clipping the Shang

翦商

The Shang dynasty, a superpower that bestrode the Yellow River valley from roughly 1600 BCE to 1045 BCE, boasted its own writing system, had unparalleled technical prowess, and ruled by fear. In Clipping the Shang, a nonfiction bestseller in China, historian Li Shuo examines one of the most brutal customs of the Shang: human sacrifice. During this era, human skulls were polished and made into bowls for religious purposes, and human sacrifices were often mingled with animal offerings. With chilling details, Li describes the methods of slaughter and the condition of the unearthed bones that archeologists have found. Why was human sacrifice so prevalent during the Shang, and how significant was the Shang’s defeat by its successor, the Western Zhou dynasty? Through the study of oracle bones, archaeology and ancient texts such as The Book of Songs and the I Ching, this book reveals a historical chapter of China that is both bleak and eerily familiar.

Immortal Li’s Trouble

太白金星有点烦

It’s Journey to the West, but told from the perspective of those who actually made it happen. Immortal Li, a mid-level celestial bureaucrat, is one step away from being promoted to a god when he is tasked with planning Xuanzang’s famous pilgrimage. A myriad of problems follow — from onboarding the monk’s unruly companions, to orchestrating the 81 trials demanded by such trips. In order for the journey to be a success, Immortal Li has to navigate through a web of nepotism, red tape and infighting that is a feature of any Chinese government, celestial or not. Meanwhile, a question brews at the back of his mind. Which quality makes a better god (or official): empathy toward those who have been wronged, or apathy toward affairs that don’t concern oneself? From China’s best-selling historical novelist, this irreverent, entertaining and imaginative political satire is not to be missed.

The Death of a Princess

公主之死

The Princess of Lanling, aunt of Emperor Xuanwu of Northern Wei (484-515), has died from a miscarriage. Her husband has run away, after kicking her out of bed in the heat of a fight; they were quarreling about his affair with two women, the latest in a decade of infidelity. The Queen Regent, furious over her sister-in-law’s demise, metes out severe punishments to the husband, his mistresses, and their brothers for good measure. Her decision is met with strong opposition from the officials, prompting a legal debate. In this new edition of The Death of a Princess, a classic of legal history which first came out in 2001, Taiwanese scholar Li Zhende focuses on this singular, well-documented case to show how patriarchy and Confucianism seeped into Chinese legislation over centuries, resulting in distinct legal treatment for men and women, and shaping how ancient — and contemporary — Chinese viewed marriage, domestic violence, jealousy and monogamy.

Modern Marriages

五四婚姻

The men were busy changing the world, but would they extend the rights they championed to their partners? This is one of the scathing questions that Hong Kong scholar Eva Hung asks in Modern Marriages, a book reexamining the marriages of prominent early modern Chinese men, from their spouses’ and lovers’ points of view. For many Chinese, the 20th century was the crossroad where Confucian values and Western ideas clashed. As they strove to save their war-torn country, intellectuals such as Lu Xun and Hu Shi came to view their arranged marriages as shackles preventing them from embracing a liberal, modern lifestyle. But divorce, like marriage, had different prices for husbands than for wives, argues Hung. How were the women affected by their husbands’ neglect and abandonment? How did they respond to the changes happening around them? What did a modern woman look like? Published in simplified Chinese this year (following a 2014 Hong Kong edition), Hung joins the debate among mainland readers about gender equality and women’s empowerment.

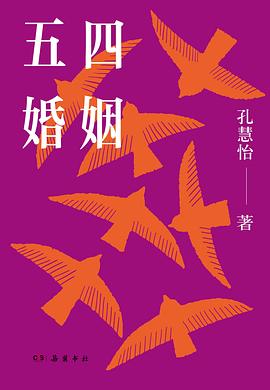

From Khanbaliq to Xanadu

从大都到上都

In 2016, historian and hiking enthusiast Luo Xin embarked on a series of walks, retracing the imperial route taken by the Mongolian Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) emperors to commute between their winter capital, Khanbaliq (today’s Beijing), and their summer capital, Xanadu (Shangdu, 220 miles north). His trips led to this richly layered book, blending his notes with historical texts and the writings of previous travelers whose paths overlapped with his. The book’s selection of poems composed by Yuan literati is also enjoyable, adding texture to the lives of Han Chinese living with ethnic groups different from their own. Contrasts abound when this historical landscape is superimposed on the present. At one remote village along the route, a loudspeaker blared announcements pressing Party members to attend their regular study sessions. Whether intentionally or not, Luo almost never comments on moments like this, leaving readers to ponder over the brevity of power, and the eternity of time. ∎

Hailing from Chengdu, Na Zhong is a New York-based fiction writer and literary translator. Her work has appeared in Guernica, A Public Space, Lit Hub and others. She co-founded the bilingual creative community, Accent Society, and co-hosts the Mandarin literary podcast 跳岛FM. Na is a 2021-2022 Center for Fiction Emerging Writers Fellow, and a 2023 MacDowell Fellow.