China’s online population at the start of 2003 was less than 60 million. 10 years later, it was fast approaching 600 million. Now, after 20 years, it is well over a billion.

In the closely monitored Chinese digital sphere, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) views all Internet users as subjects to be controlled and guarded against, as well as potential economic assets. On social media platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, Douyin and Zhihu, netizens actively oppose censorship and propaganda through strategic, well-timed actions focused on specific issues and tactical opportunities. Their resistance is marked by diversity, creativity and adaptability, often emerging spontaneously and organically, without the need for formal organization. In the dynamic landscape of Chinese social media, these individual acts of defiance merge, creating a significant collective impact on public opinion.

Every major debate on the internet represents a battle of narratives. While state censors and government-supported online commentators strive to filter, suppress, distort or erase varying viewpoints, the tenacity of netizens — voicing opinions, documenting events, sharing narratives and engaging in discussions — counters them. Despite the extensive censorship apparatus, the combined voices and inventive resistance of millions of Chinese social media users present a formidable opposition that no censorship system can completely silence.

In response to netizen activities, censors often resort to deleting posts and ramping up the monitoring of “sensitive words,” which in turn gives rise to various subtle forms of resistance discourse. Netizens have developed a repertoire of techniques such as satire, mockery, roasts, provocations and intentionally contrarian interpretations. A key component of this is the use of parody, in which netizens ingeniously manipulate and reinterpret symbols and slogans from official propaganda. These collective efforts repurpose elements from both official and popular culture, turning them into instruments of subversive expression. This creative defiance generates internet buzzwords that, while subtle, represent a powerful form of digital resistance.

On a more profound level, the aggregation of these seemingly minor terms constitutes a rich, emotive lexicon, akin to an ever-expanding “coral reef” within the history of resistance on the Chinese internet. My aspiration is that this coral reef of dissent will eventually grow substantial enough to become an integral part of the broader narrative, effectively grounding the colossal vessel of the CCP’s legitimacy.

Since 2003, China Digital Times has been at the forefront of tracking and preserving information that faces censorship on the Chinese internet. Using automated technology and the crowd wisdom of Chinese netizens, our editors capture content suppressed by the Party-state, as well as the varied ways in which netizens combat censorship and propaganda. Our archive contains narratives and expressions stifled by official media, personal accounts from marginalized voices, and insights revealing the inner workings of China’s censorship and propaganda systems.

The 20 phrases below, presented chronologically across two decades, are excerpted from 104 terms in the 20th-anniversary edition of the China Digital Times Lexicon (originally titled the “Grass-Mud Horse Lexicon,” after one of its entries). The full lexicon was selected by our Chinese team, who have spent a collective century or more deeply immersed in Chinese online discourse, from official slogans and their irreverent appropriations to protest cries and nationalist accusations. It aims to capture something of the enormous explosion of online speech that accompanied this growth of the Chinese internet, with a particular focus on efforts by authorities to tame it, and by others to push back.

– Xiao Qiang, Founder and Editor-in-Chief, China Digital Times

2004 — Five Times Better (haowubei 好五倍)

A phrase from an argument that Sha Zukang, former Chinese ambassador to the United Nations, made to the press in April 2004 in defense of China’s human rights record.

In his statement to the press, Sha employed some dubious mathematical logic to support his claims about China’s human rights record:

I have openly remarked that the human rights situation in China today is better than that in the United States. The population of China is five times larger than the population of the U.S. If you look at it just in terms of comparing the populations, one would expect China’s problems to be at least five times greater than those of the U.S. in order for our human rights situations to be the same. But the reality is that our human rights situation is better than that of the U.S. — this shows that China’s human rights situation is five times better than that of the U.S.

Sha is known for other less-than-diplomatic statements. He caused a stir in September 2010 when he declared his distaste for Americans and U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. “I know you never liked me Mr. Secretary-General — well, I never liked you, either.” In 2007, The Onion published a satirical commentary, purporting to be penned by Sha, under the headline: “I’m the U.N. Undersecretary Your Mother Warned You About.”

The phrase “five times better” has also been used on Chinese social media to mock exorbitant claims or grandiose plans by the government. In response to an August 2014 news item about the Chinese Communist Party investing 20 billion yuan to build a Party school in South Africa, Weibo user @人生药师 wrote: “Now that the people of South Africa finally have a Party school, and finally have human rights that are five times better than America’s, Mandela can rest in peace at last.”

2005 — Your Party (guidang 贵党)

“your country” (贵国), also

meaning “expensive country”

A term used by critics and opponents of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to distance themselves from the CCP, by emphasizing that it is “your party” rather than “my party” or “our party.” It is also used to highlight the fact that although China is a Party-state, the CCP is not equivalent to the nation as a whole and, contrary to the CCP’s own insistence, Party interests do not necessarily favor the interests of the nation or the people.

In the original, unironic usage of the term, gui 贵 is an honorific meaning “esteemed,” “noble,” or “honorable,” while dang 党 refers to a political party. In formal diplomatic language, it is still used in the sense of “your esteemed/honorable [political] party.” In the related term “Your esteemed/honorable country” (guiguo 贵国), also found in diplomatic texts and speeches, the honorific is attached to the character for “country/nation/state” (guo 国).

“Your party” and “your country” can also be expressed more directly by using the character literally meaning “you” (ni 你), but these sound less sardonic than variations using the high honorific gui 贵. Note that these various terms of disenfranchisement and disenchantment are the polar opposite of the patriotic formulations “my/our Party” (wodang 我党) and the very common “my/our country” (woguo 我国), which communicate a strong sense of pride and identification with one’s nation or political party.

The sarcastically honorific forms “your party” and “your country” are generally used in resistance discourse, but they are occasionally found in nationalistic discourse on social media, as well. A nationalist might ironically congratulate another country (or an overseas political party) for some failure or political misstep, for example.

2006 — River Crab (hexie 河蟹)

A troublesome creature whose name echoes the CCP’s treasured “harmony” (和谐) and serves as a euphemism for censorship.

Originally a Confucian concept, the idea of “social harmony” was resurrected as a key tenet of Hu Jintao’s “scientific development concept” and used as a motto to embody his governing philosophy. The Hu administration introduced its doctrine of “harmonious society” (和谐社会) in 2006, broadening the Party’s focus from raw economic growth to ameliorating income inequality and other threats to social stability. Critics of this philosophy argued that the government created a surface appearance of harmony by suppressing or “harmonizing” elements of society that were not to the Party’s liking.

As online communication and mobile phone use spread, Hu’s reigning doctrine of “harmony” became a euphemism for censorship. In some online forums, the word “harmony” itself became a banned keyword. In order to circumvent such censorship, netizens replaced it with the homophone “river crab” or other similar-sounding terms. Ultimately, netizens used the word “river crab” to refer broadly to the government’s behavior of blocking terms and foreign websites, covering up negative news, and otherwise curtailing freedom of speech and information.

The word can also be used as a verb: censored content can be said to have been “harmonized” (被和谐了), or to have been “river-crabbed” (被河蟹了). At one point, the “river crab” was even retrofitted into the text of a short, satirical Ming dynasty verse originally written by an anonymous poet to mock Yan Song, a notoriously corrupt Ming regent. Chinese internet users changed the word “crab” to “river crab” to give the line an update: “I shall keep an eye upon that river crab, and see how much longer he manages to scuttle about.”

The river crab is sometimes depicted wearing three watches (带三个表), a play on words referring to the “Three Represents” (三个代表), the defining governance theory of Jiang Zemin, as well as the once hot phenomenon of spotting officials wearing luxury timepieces costing many times their official salaries.

2007 — Take a Walk (sanbu 散步)

Walking as an innovative, moderate form of civil disobedience to avoid more provocative forms of protest — such as marches, demonstrations, or sit-ins — that would be easily suppressed by authorities.

In China, it is difficult to strike, applications for protests are routinely denied, and petitioning the government often brings dire consequences. As such, workers and citizens have constantly adopted new methods that tread the fine line of legality. One of these innovative forms of resistance that began as early as 2007 is “taking walks,” which mobilizes large numbers of people to walk together in the name of a common cause, without necessarily labeling it explicitly as a protest. The more innocent terminology also facilitated online organizing without the use of easily filtered keywords. This allows citizens to legally express their opinions while (hopefully) avoiding scrutiny by authorities. In recent years, as such peaceful “walks” have become riskier and less common, the term has fallen out of use somewhat.

In the spring and summer of 2007, a text-message campaign rallied citizens in Xiamen to begin “taking walks” to protest the construction of a paraxylene (PX) processing plant, which was ultimately moved to another location. In February 2011, an online source attempted to stage a pro-democracy “Jasmine Revolution,” echoing language used to describe the various Middle East protest movements, by encouraging groups to “walk” the central Beijing shopping district of Wangfujing. An open letter by the anonymous organizers called on people to gather every Sunday in 13 cities for a low-confrontation approach, without banners: “We invite every participant to stroll, watch, or even just pretend to pass by. As long as you are present, the authoritarian government will be shaking with fear.”

In 2014, a series of state-led campaigns against “illegal religious buildings,” in which churches were demolished and crosses removed, generated fierce resistance amongst Chinese Christians. Taking a walk was one of the tactics that Christian groups employed to defend their religious freedom. A 2014 post on Weibo from user @廖木林传道 announced one such potential walk:

If Zhejiang authorities do not immediately put a halt to the illegal removal of crosses, tens of thousands of Christians will don protest t-shirts and take a spontaneous walk through the streets to protect our rights. We will hold protest signs to express our feelings to the entire world.

2008 — Fart People (pimin 屁民)

(Southern Metropolis Daily)

Originally an insult, “fart people” was reclaimed as a self-deprecating label of pride for the common people. The term comes from a 2008 incident involving Lin Jiaxiang, former Party Secretary of the Shenzhen Maritime Administration, who was caught on surveillance camera harassing an 11-year-old girl. He asked her where the bathroom was, then cornered her after she showed him the way. After the girl escaped, her parents confronted Lin. Angrily pointing at the girl’s father, Lin shouted:

Do you people know who I am? I was sent here by the Ministry of Transportation. I’m on par with your mayor. So what if I pinched a little child’s neck? You people are worth less than a fart to me! How dare you mess with me? Just see how I deal with you.

“You people are worth less than a fart to me” was picked up online, giving rise to the designation “fart people” as a sardonic reflection of the people’s perceived standing in the eyes of officials. “Fart people” originally stood in inherent opposition to officialdom as, for example, in the derivative phrase “the system errs, the fart people suffer” (体亏屁思). Amid severe air pollution in 2013, when the China National Committee for Terms in Sciences and Technologies was seeking a Chinese term for “PM 2.5,” one suggestion floated online substituted “fart people” (pimin) for the acronym’s original “particulate matter.”

The dichotomy of officials vs. fart people has faded somewhat over time. In their 2013 essay “China at the Tipping Point? From ‘Fart People’ to Citizens,” Perry Link and Xiao Qiang observed that while the term “began as a bitter suggestion that powerholders see rank-and-file citizens as having no more value than digestive gas [… now] it is just another way to say laobaixing (ordinary folks). But the seemingly innocuous process by which sarcastic terms are normalized can have profound consequences. It converts the terms from the relatively narrow role of expressing resistance to the much broader one of conceiving how the world normally is.”

2009 — Grass-Mud Horse (caonima 草泥马)

for the grass mud horse (CDT)

De facto mascot of Chinese citizens fighting for free expression, symbolizing defiance of online censorship.

The grass-mud horse, whose name sounds nearly the same as the phrase “fuck your mother” (肏你妈), was originally created to skirt government censorship of vulgar content. Film scholar Cui Weiping draws a direct connection between the launch of the “Special Campaign to Rectify Vulgar Content on the Internet” in early 2009 and the appearance of the viral music video “Song of the Grass-Mud Horse” in February of that year. The idea caught fire after the creation of a video depicting the imaginary grass-mud horse defeating the likewise mythical river crab (see above). Users continually expanded the lore of the grass-mud horse by composing catchy songs and creating photo albums and fake nature documentaries purporting to show the creature in its natural habitat.

An annual “Grass-Mud Horse Festival” is held on July 1, the anniversary of the CCP’s founding. The grass-mud horse is one of many mythical creatures invented in response to increasingly strict censorship measures. Naturally, the grass-mud horse itself has long been targeted by government censors. More recent examples of (partially) censored fictional creatures include Winnie the Pooh and Peppa Pig.

Over a decade later, its image still serves as a powerful rebuke to government censorship, such as in November 2022 when a woman brought three alpacas to Shanghai’s Wulumuqi Road following an online crackdown on the White Paper protests that began at that intersection. A May 2015 comment from Weibo user @弹力晗超人 expresses the frustration of having to constantly play a game of cat-and-mouse with online censors:

Uh … # ¥% & * + “$ & …posting, getting deleted, and then reposting. I can no lon- ger find the words to describe the number of grass-mud horses that are currently on my mind.

2010 — Loser (diaosi 屌丝)

A reclaimed epithet, literally “dick hair” or “pube,” which emerged from a clash between rival message boards in 2010, and soon surged to widespread adoption as a self-deprecating expression of alienation and lack of aspiration. By April 2013, the term had briefly graced a giant ad billboard in New York’s Times Square; according to one perhaps dubious marketing survey, it was embraced by 40% of Chinese, a segment variously seen as a profitable target market and a potential wellspring of political change.

The term is most usually described as equivalent to “loser” in the defiantly reclaimed sense of Beck’s 1993 slacker anthem. Charles Custer suggested the gradual reclamation of “geek” as an alternative parallel, while at That’s Beijing, Karoline Kan compared it with “‘redneck,’ whose poverty and unrefined behavior can not only be a source of pride, but a culture in and of itself.”

A 2012 blog post archived by CDT Chinese (which noted an undercurrent of incel-like misogyny and objectification in diaosi culture) described the phenomenon:

Diaosi come from all over the country, usually from rural families or the lowest rungs of urban society. Some manage, against great odds, to complete 12 years of study and go on to major in sciences at university, but find that the subsequent reality of work doesn’t live up to their expectations: the yield is not proportionate to their investment, and not worth the effort. Others drop out of school after junior high, and move to a city for work, or to work in a hair salon or internet café, competing for a tiny slice of the big-city pie. Or they may become unemployed drifters, unwilling to admit it and posing online as “self-employed.” [….] Diaosi like to describe themselves with the three attributes “poor, short, and ugly” (穷矮丑), as opposed to [the conventional ideal of] “tall, rich, and handsome” (高富帅).

2011 — Dinner and Drinks (fanzui 饭醉)

edition of Esquire, August 2009

To discuss or engage with politically sensitive issues, usually as a group over food and drink; homophonous with “to commit a crime” (犯罪).

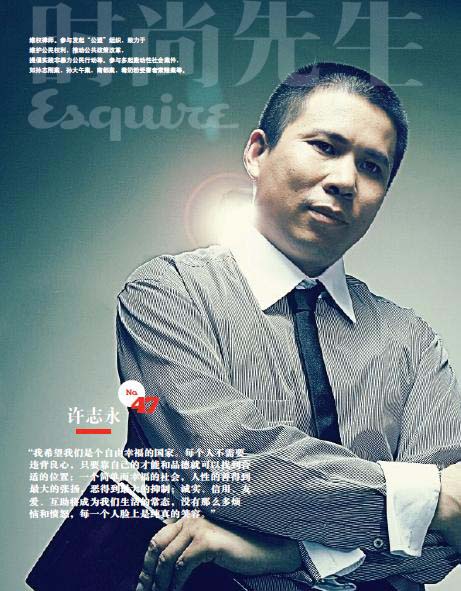

The term comes from a practice of the New Citizens’ Movement to gather for dinners and discuss political and social issues. These gatherings were sometimes referred to as “getting dinner and drinks in the same city” (同城饭醉 tóngchéng fàn zuì), which sounds identical to “committing a crime in the same city” (同城犯罪 tóngchéng fàn zuì).

The practice began around 2011, starting with small gatherings of legal professionals who discussed cases and current events, either on a regular basis or on the spur of the moment. As more people were encouraged to participate, the gatherings spread to over 30 cities with as many as 200 people at a given dinner. The topics expanded to cover environmental pollution, CCP history, government corruption, censorship, land expropriation, models of democratic governance and other sensitive topics. All participants were given time to voice their opinion on the subject, before the group agreed on a proposal for action.

The New Citizens’ Movement called for democratic and rule-of-law reforms, constitutionalism, human rights, and social justice. After authorities detained rights lawyer Xu Zhiyong, a central figure in the movement who gave it its name, and a dozen other members of the group in 2013, the dinners continued, but fewer people attended. The 2015 “Black Friday” arrests of hundreds of civil rights lawyers, and the continuing repression of civil society groups under Xi Jinping’s tenure, made such dinner gatherings even riskier. In 2019, Xu and Ding Jiaxi organized another dinner gathering of the New Citizens’ Movement in Xiamen, but authorities tracked down and arrested the participants. In 2023, Xu and Ding were pronounced guilty of “subversion of state power” in closed-door trials and sentenced to 14 and 12 years in prison, respectively.

The idealism and excitement of these once-common gatherings is palpable in this 2013 comment from Weibo user @马玉清 风, who responded to an announcement about monthly “civic-participation” dinner parties in Xiamen by posting:

“Dinner-and-drinkers, empower yourselves by building consensus with fellow citizens of your city!”

2012 — Positive Energy (zheng nengliang 正能量)

in People’s Daily online

Unreserved enthusiasm in news, art, culture and beyond for Party rule and anything that might reflect on it, as well as a rhetorical cudgel against any deviation from that tone.

After an inauspicious first life in 2010, as a meme based on an accused sexual assailant’s curious euphemism, via its use as a catchphrase in Zhang Lixian’s 2012 film Beijing Blues, “positive energy” erupted to its current prominence with the dawn of Xi Jinping’s leadership in 2012. It soon found a place, in David Bandurski’s words at China Media Project, “at the very heart of political discourse in the Xi Jinping era,” and thoroughly permeated official speech at other levels. Bandurski added that “the devilish genius of ‘positive energy’ is the way it seems more spiritual than ideological, as though it isn’t about exercising control over the minds of the population so much as engaging in a national project of self-help.”

The relentless pumping of positive energy has repeatedly led to backlash. In a set of interviews with mainland Chinese journalists from the then Hong Kong-based Initium Media in 2018, one lamented:

Later on, we could only do the youngster rescuing people from a fire, the public bus driver slamming the brakes to save people, that kind of “warm hearted” thing. But is “warm hearted” this society’s true state of affairs? And these “extolling positive energy” pieces, the most beautiful female cop stories, most beautiful city administrator stories, most beautiful government official stories, do they have any meaning?

[…] Everything was feeling more and more meaningless. I finally had no choice but to retire.

2013 — Catch the Frisbee (diaofeipan 叼飞盘)

as a veiled criticism of Hu Xijin (CDT)

Eagerly latching on to (and putting a positive spin on) whatever rhetoric the government throws out, much like a dog catching a frisbee. Most commonly associated with Hu Xijin, former editor-in-chief of the nationalist Party-owned tabloid Global Times (环球时报).

Hu Xijin earned the nickname “Frisbee Hu” (飞盘胡) for his track record of diligently latching on to and reinforcing government propaganda. From 2005 to 2021, Hu led Global Times, a tabloid subsidiary of People’s Daily known for its nationalism and pro-government stance. Hu personally is known for being an outspoken “wolf warrior” on Chinese and Western social media. While he boasts a sizable following, he is often criticized for his incessantly positive spin on questionable government talking points.

The nickname spread during a controversy around the 2013 New Year message from progressive and out-spoken newspaper Southern Weekly. After the government sparked public outrage by censoring the message, other outlets were forced to republish a Global Times editorial backing the decision. When Hu tried to defend the editorial, a Southern Weekly editor expressed an oblique criticism of Hu by posting on Weibo a photo of a dog catching a red frisbee, with the caption: “A ferocious moment as a dog catches the frisbee.” An editor at Nandu.com, a news website affiliated with the Southern Metropolis Daily, went a step further by creating a photo collection of frisbee-catching dogs with the title: “The Greatest Moments of the Frisbee-Catching Dogs of the Global Times.”

Later that year, amid fallout from the Bo Xilai scandal, Hu published an editorial titled “Bo’s Case Shows Resilience of Rule of Law.” Some Chinese internet users scorned Hu’s attempt to find a silver lining in the scandal and wondered why, if the rule of law was so resilient, Bo was not questioned earlier for a pattern of alleged misconduct that stretched over decades. One Weibo user posted:

“No matter how far his masters throw the frisbee, Master Hu will always fetch it back for them.”

In February 2014, when Hu wrote a Weibo post complaining that his political commentary had made him a target of critics, the online community piled on even more criticism, with Weibo user @平壤热线 writing: “Frisbee Hu, what happened to you? Smell something in the wind again?”

2014 — Be Represented (beidaibiao 被代表)

(Harvard Library)

A sardonic expression referring to Chinese authorities’ claim to be the sole legitimate representatives of the Chinese nation and its people. Although grammatically identical to a neutrally passive statement, the term often carries the same sardonically contradictory barb as an English phrase such as “to be volunteered.” To “be represented” in this sense is to have the Party speak and act on your behalf, regardless of your own thoughts on the matter.

In a 2014 article published in the International Journal of Chinese Linguistics, C.-T. James Huang and Na Liu wrote:

“bèi XX constructions are used in satirical writings and can be interpreted in three ways: (a) ‘x gets reported or regarded as having the property denoted by XX; (b) ‘x is forced to acquire the property denoted by XX’; (c) ‘x is treated, acted upon, in a way involving or described by XX’.”

Further examples of each of these usages include:

- To be happiness-ified (被幸福), or supposedly made happy by the state.

- To be donored (被捐款), or forced to donate.

- To be traveled (被旅游), or escorted on a trip to ensure one’s absence from a sensitive location at a sensitive time.

- To be mentally-illed (被神经病), or subjected to involuntary psychiatric detention on spurious grounds.

- To be tea-drinked (被喝茶 bèi hē chá), or questioned by public security or other officials.

- To be wall-raped (被墙奸 bèi qiángjiān, a pun on “to be raped” 被强奸), or blocked by the Great Firewall.

- To be river-crabbed (被河蟹 bèi héxiè), or harmonized — that is, censored (see entry).

2015 – Reincarnation Party (zhuanshidang 转世党)

A collective name for those posting under new social media accounts after their prior accounts have been banned by platform censors.

The name comes from the Buddhist concept of reincarnation. Users who post about sensitive topics may have their social media accounts suspended or deleted by the company running the platform, often without any explanation. In such cases, a user can then “reincarnate” on the same platform by creating a new account, often named after the old one but with labels to designate that it is a “reincarnated” account, sometimes by including numbers or the word “reincarnation,” to make it easier for their previous followers to find. The term first applied to Weibo, and has since spread to other social media platforms.

Political cartoonist Kuang Biao reincarnated dozens of times on Weibo, and for several years included his reincarnation count in each successive username: as of May 2015, for example, his incarnation was “Uncle Biao Fountain Pen Drawings 47” (@飚叔钢笔画47). One Weibo user named “Repair” reportedly reincarnated a record-holding 418 times. In 2011, after DeutscheWelle’s official Weibo account account was deleted, the media outlet said it was “forced to re-incarnate again under the tyranny of Sina [Weibo].” In 2013, Taiwanese politician Hung Chih-kune attempted to sue Weibo for repeatedly deleting his account and forcing him to reincarnate.

China’s government, although formally atheist, also claims authority over spiritual reincarnation under the “Measures on the Management of the Reincarnation of Living Buddhas” issued by the State Administration for Religious Affairs in 2007. These regulations detail the bureaucratic requirements for permitting, locating, verifying, and approving reincarnations of Buddhist religious leaders.

2016 — Driving in Reverse (kaidaoche 开倒车)

reversing off a ledge

A derisive metaphor used to satirize Xi Jinping’s governance of China, which users of the phrase view as being regressive, or going in the wrong direction, particularly in terms of its escalating emphasis on the singular, extended rule of “core leader” Xi himself.

Several viral online incidents helped propel the phrase “driving in reverse” to popularity. In June 2016, People’s Daily posted a video to Weibo of a Volkswagen Tiguan reversing down a ramp and falling off a ledge, along with this warning: “Driving in reverse is a task that requires real technical skill!” Weibo users flocked to the comment section to draw parallels with Xi Jinping’s governance, highlighting the danger of going backwards, lest it result in a “hard landing” and the need to “step down.” One user offered this assessment:

“Correct answer: Backwards drivers need to step down!”

In November 2018, Bilibili was revealed to be prohibiting comments on all videos in search results for “driving in reverse.” This applied to comments on videos that had nothing to do with politics or that simply had the phrase “driving in reverse” in their title or description, as well as comments from usernames containing the phrase. When one netizen asked a customer service representative to explain the reasons for this ban, he was told that the phrase “touches on sensitive topics.”

2017 — Rice Bunny (mitu 米兔)

sign outside a courthouse in 2020 (CDT)

A homophone for the English “Me Too,” in reference to China’s social movement against sexual harassment and sexual abuse. In order to avoid online censorship, feminist activists resorted to using the homonym 米兔 (mǐ tù), literally “rice bunny,” as well as the synonym “我也是” (wǒ yěshì), literally “me too.”

The hashtag #MeToo (first coined by activist Tarana Burke in 2006) began to go viral on American Twitter in late 2017, and in January 2018, China had its first online viral #MeToo case. Luo Xixi (罗茜茜), a doctoral student at Beihang University in Beijing, revealed on WeChat that she had been sexually harassed by her academic supervisor. To support those discussing the topic online, feminist activist Qi Qi (七七) shared the hashtag #MeToo在中国# (#MeToo in China#) on Weibo, which received 4.5 million views before it was banned. Students and alumni from other universities also started campaigns to draw attention to the issue of sexual harassment by writing letters and spreading related hashtags on Weibo.

Numerous cases surfaced online in the following months. In April 2018, Peking University student Yue Xin (岳昕), a Marxist and feminist activist, led a movement to uncover new information about a 1998 rape case at the university, but was harassed by school authorities and published an open letter recounting her experience. Government censors later instructed the media not to report on the incident or the open letter, and to prevent personal social media accounts from expressing solidarity.

Online discussions of the accusations have used different variations of the term “MeToo,” even if the victim does not in their initial testimony. MeToo activists weather constant censorship and victim bashing on social media, by the government, state media, and nationalist voices that attack feminism.

2018 — Awesome Country (lihaiguo 厉害国)

with satirical blurb

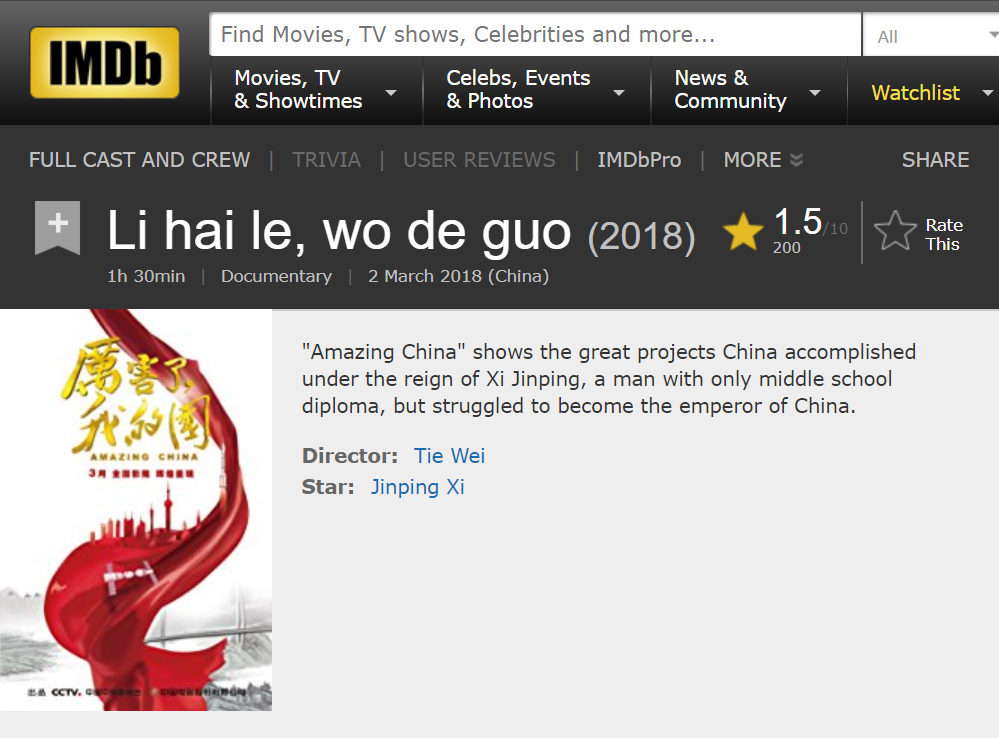

Ironic phrase, used to mock China, derived from the 2018 state-media propaganda documentary “Amazing China.”

The film was co-produced by CCTV and China Film Co, both state-owned enterprises. Its Chinese title 厉害了, 我的国 (literally “Amazing, My Country”) comes from the similar-sounding expression “厉害了, 我的哥” which means something akin to “awesome, bro.”

The film lauds Chinese achievements in science, technology, development, and poverty reduction since Xi Jinping became the country’s leader in 2012. After the film was released. its popularity was greatly exaggerated by the Chinese authorities. State media reported that it broke box office records within hours, but many people noted that some companies and schools forced their employees and students to watch the film. The State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television circulated a notice requiring all movie theaters to give the film two screenings per day on the opening weekend, in their largest theater spaces. Moreover, online ratings appeared to be controlled by censors. On Douban, the film’s “user rating” was concealed and replaced with a “media rating” of 8.5/10, accompanied by glowing reviews from Xinhua and People’s Daily.

Determined to express their opinions, internet users created a page for the film on the U.S.-based movie site IMDb, where it received a rating of 1.5/10., with the following description:

“‘Amazing China’ shows the great projects China accomplished under the reign of Xi Jinping, a man with only [a] middle school diploma, but [who] struggled to become the emperor of China.”

The Cyberspace Administration of China later asked Amazon, which owns IMDb, to remove the page for the film, and some negative reviews were subsequently deleted.

Critics of the film began referring to it as “Amazing, Your Country” (“厉害了你的国) instead of “Amazing, My Country” (“厉害了我的国”), in order to distance themselves from the CCP’s propaganda. The phrase “awesome country” was adopted as an ironic way to ridicule Chinese government boastfulness.

2019 — Brother China (A Zhong Gege 阿中哥哥)

Anthropomorphic celebrity idol created in August 2019 during Hong Kong’s anti-extradition movement to rally young Chinese in support of the police and against pro-democracy protesters.

Brother China — or “Brother Ah Zhong” — emerged from China’s growing world of online fandom. Many of its inhabitants, primarily apolitical young women, participate in highly organized “fan circles” (饭圈) that endeavor to sway social media discourse in favor of their idols. Powerful fan circles are divided into teams that are assigned different tasks to support their idol, such as drafting comments and designing images for fans to share online, disseminating content to blogs and outlets, drowning out negative news with positive stories, and coordinating all of these activities.

Over time, fan circles were recruited by members of Diba, a long-standing nationalist online forum also associated with nationalist “little pinks,” to boost their nationalist discourse power. This alignment of “patriotic youth” is emblematic of “fandom nationalism,” whereby participants love and protect their country as they do their idol. Brother China grew out of this phenomenon during the 2019 Hong Kong anti-extradition movement and was used to amplify pro-government narratives. Supporters referenced Brother China in content they shared to domestic and foreign social media sites, including Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, to defend Hong Kong police and criticize protesters and the West. One fan described Brother China’s treatment at the hands of his “ungrateful children” Hong Kong and Taiwan:

“Brother China only has us left. He was high-born but with his fortunes gone he was bullied and his children taken away from him … When he finally fared better, he immediately wanted to take his children home.”

2020 — Correct Collective Memory (zhengque jitijiyi 正确集体记忆)

A4 paper in November 2023 (CDT/VOA)

Term for the Party-state’s approved account of history, made infamous in the aftermath of the initial Wuhan Covid outbreak.

In June of 2020, the State Council Information Office issued a white paper that cast China’s initial pandemic response as an unmitigated success. The white paper elided all mention of the late Dr. Li Wenliang and other “rumormongers” who tried to warn of the emerging virus, and who were subsequently disciplined. On June 8, 2020, then-Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying dismissed all criticism of alleged opacity and misinformation about the virus, asserting:

China issued the white paper not to defend itself, but to keep a record. The history of the combat against the pandemic should not be tainted by lies and misleading information; it should be recorded with the correct collective memory of all mankind.

The phrase immediately went viral on Weibo, with a number of posters writing of their ongoing resistance to the Party-state’s control of memory, such as @Tin_Oxide who wrote: “Whatever the case, I’ve set up a folder to store a whole bunch of incorrect memories.”

Efforts to control China’s memory did not start, nor finish, with the pandemic. “Correct collective memory” was immediately applied to other instances where the Party-state has attempted to suppress alternative histories, such as the Wenchuan earthquake, the Karamay fire, the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen crackdown. The citizen journalist Lu Yuyu adopted the phrase for the episodic memoirs he published upon his release from prison in June 2020, titling the collection “Incorrect Memory.”

The push to enforce “correct collective memory” of the pandemic continued after the end of the Zero-Covid policy. When mass protests against the policy shocked the world in November 2022, Xi recast them as simply the product of “frustrated … teenagers in university.” Commemorations of the protests are aggressively censored. In 2023, the Party launched a major propaganda campaign to laud its pandemic response while eliding the once much-vaunted Zero-Covid policy. Sinologist Geremie Barmé has noted that “in Communist societies a utopian future is immutable, but it’s the past that constantly changes.”

2021 — Lying Flat (tangping 躺平)

“lying flat” (Web archive)

Giving up, or slacking off, as an antidote and method of resistance for despairing youth in the face of a hyper-competitive society.

“Lying flat” or “lying down” is a form of slacking that emerged as a response to the unrealistic expectations of success for many young people: getting into the best schools and universities; competing for high-paying jobs that demand a grueling 996 work culture (working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. six days a week); saving enough money to purchase a home in an expensive housing market; and finding a partner for marriage and having kids, all while being in one’s mid-twenties. It is also an expression of distress at the widening wealth gap between the rich and the poor, and at the lack of upward mobility for those in the middle class. The term emerged around the same time as “involution,” which refers to a sense of burnout and unhappiness brought on by pursuing all of the benchmarks above, and questioning the purpose of that pursuit. In order to push back against “involution,” many young Chinese are simply choosing to “lie flat.”

“Lying flat” dates back to at least July 2020, when a Douban group formed around the concept. The term really took off in May 2021, when the Communist Young League’s (CYL) official Weibo account posted a tribute to young patriots with the hashtag #TodaysYouthNeverLieDown (#当代年轻人从未选择躺平). The CYL disabled the post’s comment section after it was flooded with thousands of angry replies criticizing this perceived insensitivity to young people’s struggles. Days later, a Douban “lie-downism” group with almost 10,000 members was banned. Around the same time, searches for the term on Zhihu were blocked. Later, the Cyberspace Administration of China mandated that products branded with “lie down, lie-downism, involution” and the like be removed from e-commerce sites.

A May 2021 comment in response to the closure of Douban’s “lie-downism” group expresses frustration with the increasingly long list of activities — including slacking off — that the government will not allow:

Feminism isn’t allowed, lying flat isn’t allowed, only endless burnout is allowed. They insist that only suffering and selfless dedication will bring about just rewards. I wonder where this will all end, with no guarantee of basic human rights and no happiness in sight.

2022 — The Last Generation (zuihouyidai 最后一代)

control workers (YouTube)

A rallying cry for China’s disenchanted, inspired by a Shanghai man’s lockdown defiance. In a video published in May 2022, three “Big White” pandemic control workers commanded a household to move to centralized quarantine. A man explained that the Big Whites did not have the authority to compel them to do so. One of the Big Whites then threatened him: “After we punish you, it will influence your next three generations.” The man calmly replied, “We’re the last genera- tion, thank you,” then closed his apartment door. The video went viral, with “the last generation” becoming shorthand for the profound dissatisfaction of Chinese youth.

Chinese human rights lawyer Zhang Xuezhong wrote on Twitter:

This phrase, redolent of tragedy, is an expression of the deepest form of despair. The speaker declared a decision of a biological nature: we will not reproduce. This decision is underpinned by a psychological and existential judgment: a future worth striving for has been taken from us. It is, perhaps, the strongest indictment a young person can make of the era to which they belong.

Censors took down the video and deleted commentary on it from social media. Posts mentioning it or using it as a hashtag were removed from Weibo and WeChat, and Weibo searches for “last generation” returned no results. Some users wrote the phrase into their usernames and bios in an apparent effort to avoid censorship. A number of people reshared a still from a biopic about the executed late-Qing reformer Tan Sitong, in which he asks, “In today’s China, is it one more child or but one more slave?”

The phrase became a dual protest against both the tyranny of harsh lockdowns and the state’s natalist push — and a defiant counterpoint to “correct collective memory” of the pandemic. When People’s Daily published a blithely upbeat retrospective of the year 2022 with the hashtag #12SentencesRecollecting2022#, one user suggested the real phrase of the year was, “We’re the last generation.”

2023 — ChatXJP

A play on the term “ChatGPT,” used to highlight the censorship of AI-powered chatbots in Xi Jinping’s China.

Controlling the use of AI-powered chatbots became a major concern for the Chinese government following the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT chatbot in November 2022. In February 2023, Chinese regulators told Tencent and Ant Group to restrict access to ChatGPT over fears that it would give “uncensored replies” to politically sensitive questions, and regulators told the tech firms to report to officials before launching their own chatbots. That month, an early rival to ChatGPT appeared in China, called “Yuanyu AI,” but its WeChat mini-program and online test page were shut down less than a week after its debut, likely due to the answers it gave to political questions.

AI-powered chatbots that eventually emerged from Chinese companies have appeared neutered. Tests of Baidu’s chatbot Ernie, which was unveiled in June 2023, revealed that it shut down when asked about politically sensitive topics and delivered answers that parroted CCP talking points. It refused to answer whether Xi Jinping’s zero-Covid policy was a success or a failure, and when asked to recount the events of June 4, 1989, it stated: “How about we try a different topic?” It also refused to answer questions about Xi Jinping and other top CCP leaders. Comments on Weibo and Chinese Twitter ridiculed these censored chatbots by calling them “ChatXJP,” and lamented that such censorship would hinder the development of AI technology in China:

贺仁平: It was over before it even started.

硕学逗唱: Strong(-ly censored) artificial intelligence.

dukeofsouthwest: @chatxjp

Vnana_zhr: Before each answer, the AI must add, “As the Great Party General Secretary Xi once said…”

SoapBrown: To enter China, AI must first join the Chinese Communist Party and study Xi Jinping Thought.

Until May, 2023, U.S.-based AI imagery generator Midjourney, which was used to create the cover of this ebook, specifically blocked attempts to create images of Xi Jinping, while allowing those of other world leaders and public figures. Prompts including references to Xi were rejected with a warning that “Circumventing this filter to violate our rules may result in your access being revoked.” Midjourney later abandoned this blanket block in favor of automated context analysis. As of December 2023, the new system will allow Xi to ride an alpaca, but not to eat crab. ∎

Text adapted from the 20th-anniversary edition of the China Digital Times Lexicon (originally titled the “Grass-Mud Horse Lexicon”), published online December 28, 2023.

Xiao Qiang is founder and editor-in-chief of China Digital Times, an adjunct professor at UC Berkeley’s School of Information, and director of the school’s Counter-Power Lab, which focuses on digital rights and internet freedom. A theoretical physicist by training, Qiang was born in China and moved to the U.S. for his PhD studies in 1986. He was executive director of Human Rights in China from 1991-2002, and has served as vice-chairman of the steering committee of the World Movement for Democracy. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 2001, and has published widely on China, human rights, and internet politics.