“That is the trouble with real life; you can’t write it down as fiction because it is so impossible.” New Yorker China correspondent Emily “Mickey” Hahn may or may not have been paraphrasing her fellow Missourian Mark Twain when she wrote that line in her 1944 memoir China to Me: A Partial Autobiography. But even Twain would have paused before inventing a character who tested the boundaries of plausibility as much as Hahn did.

China to Me is a wild ride through some of the most turbulent settings in modern Chinese history: Shanghai in the 1930s, wartime Chongqing, and Hong Kong under Japanese occupation. Through it all, Hahn centers the narrative on herself and her (sometimes outrageous) life choices, prefiguring not only the “correspondent in China” genre, but also the new school of journalism later made famous by Norman Mailer, Joan Didion and Hunter S. Thompson.

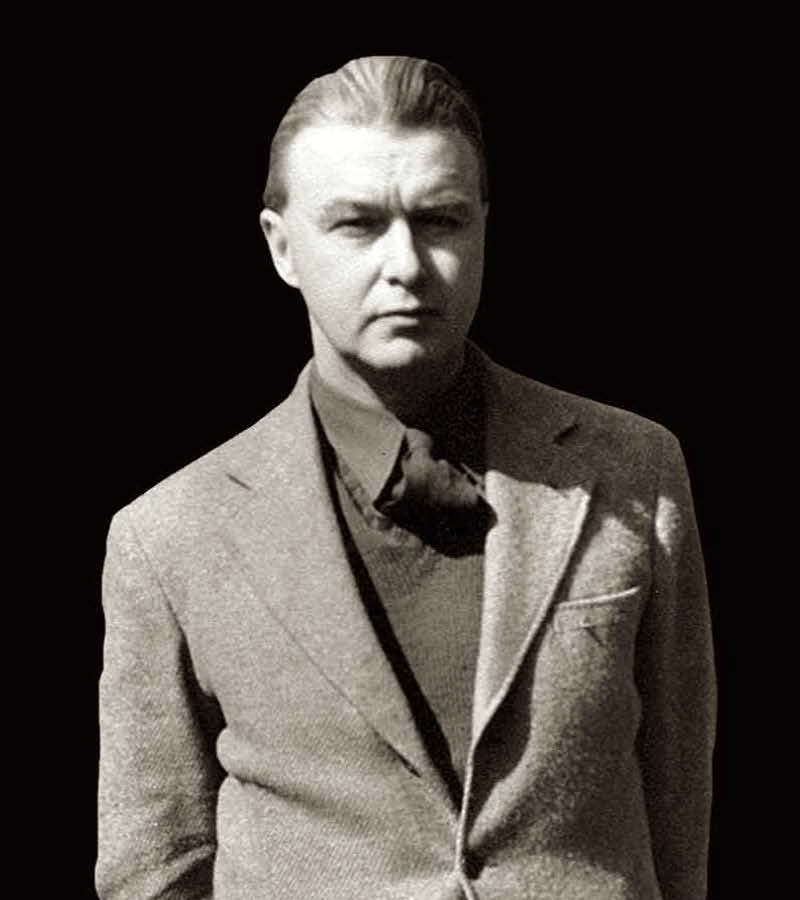

Born in 1905 in St Louis, Emily Hahn was the first woman to graduate with a degree in Mining Engineering from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. By 1930, she had emerged as a bright young thing in the literary scenes of New York and London. Hahn drank with Dorothy Parker, Ernest Hemingway and Rebecca West. Mentored by Harold Ross, the founding editor of The New Yorker, she became one of the magazine’s most prolific contributors, and her tenure at the publication spanned six decades.

In 1935, escaping the wreckage of an affair, Hahn left the U.S. and landed in Shanghai. China to Me, a memoir of her experiences, was a sensation when it was published in 1944. Readers loved her vivid descriptions, and were titillated by her tales of Shanghai society and her frank recounting of her love affairs. The book begins in Shanghai, where Hahn lived from 1935 to 1940 when she wasn’t traveling to other parts of China on assignment. Hahn (likes: booze, parties, cigars, interesting people; dislikes: social convention, gender norms, racial barriers, boring men) clearly loved Shanghai’s freewheeling, decadent cosmopolitanism:

Of all the cities of the world it is the town for me. Always changing, there are some things about it which never change, so that I will forever be able to know it when I come back. There will still be the Chinese. There will still be the old codgers, among whom I will someday take my place, drinking a little too much and telling each other how Shanghai isn’t what it used to be.

Few foreign authors captured the spirit of wartime China with Hahn’s energy and insight.

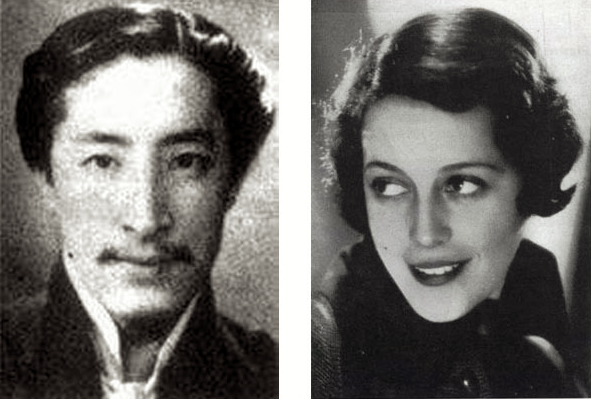

Hahn’s relationship with the Chinese poet Zau Sinmay (Shao Xunmei) was her entry point into the local literary world. They worked together on magazines and smoked prodigious quantities of opium. Although Hahn does not discuss her opium use in China to Me, she would decades later publish an article in The New Yorker, “The Big Smoke,” chronicling her addiction: “Though I had always wanted to be an opium addict, I can’t claim that as the reason I went to China.”

With the consent of his wife and children, Zau and Hahn signed marriage documents. The arrangement, while affectionate, was essentially one of convenience, intended to protect part of Zau’s assets from Japanese seizure. Tongues wagged from Hong Kong to Manhattan. The rest of Hahn’s lifestyle in Shanghai was no more conventional. She was fond of apes and kept several pet gibbons. One, named Mr. Mills, accompanied her to bars and social occasions, though Mr. Mills’ penchant for investigating neighbors’ apartments and masturbating in public made him less popular than his keeper. Hanh recalls:

I received one nervous little invitation from an Englishwoman with a penciled note on the back: ‘Sorry we cannot extend invitation to Mr. Mills.’ I was unreasonably angry and didn’t go to the party at all.

Hahn benefited from the financial advantages of living in China while earning American dollars from her book royalties and New Yorker contributions. Unlike some of her contemporaries, she was aware of her privileged position as a white American:

I was always ready to admit that it was shameful to be pulled around on wheels by another human being when I was just as able to walk as he was. But, I said, why balk at a rickshaw when you are doing just as much harm in every other way, merely by living like a foreigner in the overcrowded country of China?

Despite the favorable economics of expatriate life, Hahn struggled with managing her finances. She took on jobs that paid well but left her uninspired. (“Anyone can publish something in Shanghai, and almost everybody does.”). Fortune smiled on Hahn when she accepted a commission from her publisher in New York to write a book about the famously guarded Soong Sisters: Soong Ailing, Qingling and Meiling (married, respectively, to financier H.H. Kung, revolutionary hero Sun Yat-sen, and Chiang Kai-shek.) The Soongs, annoyed by the way they had been portrayed in the American press as a corrupt family profiting from China’s misery, were eager for someone to help them set the record straight.

Working on the book brought significant changes to Hahn’s personal life. She left Zau and her beloved gibbons behind in Shanghai and relocated — temporarily, she thought — to Hong Kong. Hahn was not a fan of the British colony, finding it a dreary place with rigid barriers of race and class, lacking the louche vibrancy of Shanghai.

From Hong Kong she traveled to Chongqing, the wartime capital of the Nationalist government. In Chongqing, she waited out Japanese air raids and interviewed Soong Ailing and Soong Meiling (Soong Qingling was less cooperative, reportedly dismissing Hahn as an unserious woman). Hahn even encountered Chiang Kai-shek, who wandered in while she was interviewing Meiling. The Generalissimo, in his dressing gown, nodded politely before making a swift retreat. Meiling smiled and excused her husband: “‘He didn’t have his teeth in.’”

The Soong Sisters was published in 1940. An unauthorized but sympathetic biography, it drew fire from left-leaning intellectuals. She answered these critics in China to Me, accusing them of offering a distorted view of China: “China doesn’t have to depend on exaggeration. The truth would have been good enough.” Yet after finishing the biography, Hahn felt bereft:

This book was not only another book, it was my life. That sounds melodramatic, but it was literally true. Because of the book I had left my home, broken up my house, deserted the gibbons and Sinmay, and lived under conditions of acute discomfort for nearly a year.

She returned to Hong Kong and purchased a ticket to America, intending to stop in Shanghai first to settle her affairs and collect the gibbons.

Hahn was fond of apes and kept several pet gibbons. One, named Mr. Mills, accompanied her to bars and social occasions.

An unexpected romance upended her plans. Hahn had first met the British historian Charles Boxer in Shanghai. The two met again in Hong Kong and quickly became an item, a relationship that lasted for the rest of her life. “I don’t want to write too much about Charles because it will sound sappy,” she admits in China to Me. They shared a fondness for a good drink (or six) after dinner, and enjoyed the local nightlife.

Boxer, an academic specializing in Japanese history, was head of British army intelligence in Hong Kong. He was married, although Boxer’s wife conveniently left during World War II as part of an evacuation of civilian family members of British officers. The relationship was an open secret in the colony, even as Boxer became increasingly embroiled in Hong Kong’s defense preparations. The situation was further complicated by the birth of their daughter, Carola, in October 1941, just weeks before the Japanese Imperial Army marched into Hong Kong.

Boxer was imprisoned in a Japanese prison camp along with other members of the British army. Hahn relied on quick thinking and connections to avoid internment and protect her daughter. In another incident of improbable non-fiction, she had a chance encounter with a relative of Zau’s, and convinced him to swear before the authorities that her marriage to Zau made her a Chinese citizen, exempting Hahn from internment. The ruse seemed to work. When the Japanese challenged her about how she could have a Chinese husband while caring for the child of an imprisoned British spy, Hahn’s retort was simple: “I’m a bad girl.”

Having refused repatriation to stay near Boxer, who remained in detention, Hahn and her daughter eventually left Hong Kong for America in 1943. She was allowed a final supervised visit with Boxer, and they reunited after the war. Such was Hahn’s fame after the publication of China to Me that Life magazine sent a team to document their reunion. The couple married in 1945 and had a second daughter, Amanda.

Their marriage was far from conventional. After a brief attempt at living together, Charles remained in England, where he took a professorship in history, while Hahn stayed in New York, traveling to research more than 50 books and 200 short stories and articles that she would publish over her lifetime. For nearly 40 years, she arrived at The New Yorker offices almost every morning, continuing to write into her final years. She died in New York in 1997, at the age of 93.

The late Roger Angell, Hahn’s friend and colleague at The New Yorker, wrote in an appreciation published shortly after her death: “She was something rare: a woman deeply, almost domestically, at home with the world.” While many books examine this era, one of the most tumultuous in Chinese history, few foreign authors captured the spirit of wartime China with Hahn’s energy and insight, making China to Me an essential addition to any China bookshelf. ∎

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.