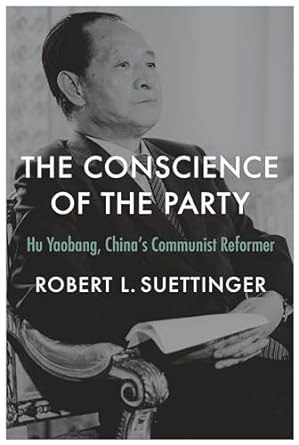

Reviewed: The Conscience of the Party: Hu Yaobang, China’s Communist Reformer, Robert Suettinger (Harvard University Press, 2024)

Developments in China during the late 1980s offer a tantalizing series of counterfactual hypotheticals. What if, in December 1986, pro-democracy student demonstrations in cities across China had not occurred? What if the cabal of elderly leaders in Beijing had not overreacted to those demonstrations, forcing Hu Yaobang’s resignation as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in January 1987? What if those leaders had not allowed Hu to retain his seat in the Politburo and attend occasional Politburo meetings? What if Hu Yaobang had not suffered a heart attack during one of those meetings on April 8, 1989, and then died in the hospital of a second heart attack on April 15? And what if there had not been a spontaneous outpouring of grief by university students on Tiananmen Square in the hours, days and weeks that followed?

If the students had not reacted as they did — or if they had been prevented by internal security forces from marching to Tiananmen Square — then Hu’s passing could have been commemorated with a quiet ceremony at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery. In this hypothetical, there would have been no trigger for the subsequent seven weeks of massive demonstrations in 1989 that brought millions of people into Tiananmen Square. If those demonstrations had not become so large and protracted — or were not covered on live television around the world — the CCP leadership would likely not have split into factions, and there would have been no excuse for China’s gerontocratic leaders to purge the reformist Zhao Ziyang, who had replaced Hu Yaobang as CCP General Secretary in 1987.

But the demonstrations did occur, the leadership did split, and paramount leader Deng Xiaoping authorized the use of lethal force to clear the square on the night of June 3, 1989. In other words: if Hu Yaobang had lived, there might have been no demonstrations, and no Tiananmen Massacre.

Halfway around the world, inspired by the bloodbath in Beijing, beleaguered East German leaders invoked the “Chinese solution” when contemplating the violent suppression of similar large demonstrations in Leipzig on October 9, 1989. Instead of a Beijing-style massacre, the authorities balked at the last moment and the Stasi did not fire on the crowds. If the “Chinese solution” had proceeded as planned, would the German communist regime have endured as its Chinese counterpart did? Instead, the East German demonstrations gained momentum, the leadership froze, and citizens breached the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, one of several communist regimes deposed in Eastern Europe that year.

Hu Yaobang (left) and Zhao Ziyang (right) in Beijing, September 1982. (Xinhua/AFP/Getty)

If Hu Yaobang had not been ousted in 1987, but had continued to work with Zhao Ziyang, China would quite likely have developed into a more liberal, open and conciliatory country. Zhao already had set up a political reform research group under the CCP Central Committee, and its members were considering a number of potential radical reforms, including direct elections up to the provincial and eventually national level; a genuinely elected and empowered national legislature; a more independent judiciary; a professional civil service; greater transparency; a freer media; enfranchised civil society; the separation of Party from both government and military; greater intra-Party democracy; and decentralizing power from Beijing to the provinces, creating a federal-style national economic and legal system.

Had these reforms proceeded, China would be a very different country. Without the Tiananmen Massacre, the regime certainly would not have become a pariah internationally, suffering as it does a lasting stigma to this day. Yet, history happens, and China would never be the same again.

If Hu Yaobang had not been ousted in 1987 … China would quite likely have developed into a more liberal, open and conciliatory country.

Hu Yaobang’s impact in death was enormous — but so too was his impact during his lifetime. In contemplating China’s evolution over the past 35 years, Hu looms large. Yet it has taken that long for a scholar to undertake a forensic historical analysis and write a definitive biography of the late Chinese Communist leader. Robert Suettinger has done so in The Conscience of the Party: Hu Yaobang, China’s Communist Reformer (Harvard University Press, 2024), a comprehensive study that sets a new standard for historiography on the CCP.

Drawing on an impressive range of Chinese-language primary source materials, the nearly 500-page magnum opus is the result of a decade’s research and writing. The book falls in the tradition of granular CCP histories by Roderick MacFarquhar, Ezra Vogel, Michael Schoenhals, Tony Saich, Chen Jian and other scholars who operate like sleuthy detectives, mining disparate Chinese sources and weaving them together. In Suettinger’s case, 72 pages of footnotes are testimony to his use of many rare books, previously untapped periodicals, and a range of online materials.

His extensive trawling on the Chinese internet reveals just how much can now be accessed outside of China, and why scholars need not necessarily travel to China to research it. In many ways, the situation of China studies today — under the strict controls and censorship imposed by Xi — is similar to that of the 1950s and 1960s, when the country was closed to foreign researchers altogether. At least today, as Suettinger’s study demonstrates, researchers can mine the Chinese internet and social media, as well as its electronic databases. Much printed material is available in libraries and private collections outside of China. Suettinger only went on one research trip to China, where he visited Hu’s tomb at Fuhua mountain in Jiangxi province.

Suettinger brings to bear decades of knowledge of the history and workings of the CCP honed from his dual background as both intelligence analyst and Sinologist. Trained at Columbia University by the late Michel Oksenberg, he entered the CIA in the late 1970s, becoming one of the agency’s top China experts, before serving on the U.S. National Security Council and National Intelligence Council. At the Brookings Institution, he also authored Beyond Tiananmen: The Politics of U.S.-China Relations 1989-2000 (Brookings Institution Press, 2004). Now, he has turned his attention to a major Party leader who catalyzed those Tiananmen protests, but who has received little scholarly attention.

The situation of China studies today — under the strict controls and censorship imposed by Xi — is similar to that of the 1950s and 1960s.

Hu Yaobang was undoubtedly an important figure in Chinese Communist history. During his career, he held more formal positions than any other Chinese leader, working in all the main organs of a Leninist Communist Party. He was head of the Central Committee’s Organization and Propaganda departments (1977-78 and 1978-80, respectively); President of the Central Party School (1977) and the Communist Youth League (1952-1978); a member of the Politburo (1978-89) and its Secretariat (1980-82), and General Secretary of the CCP (1982-87). Previously, he also served as Party Secretary of Shaanxi province (1964-65) and head of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (1975-76).

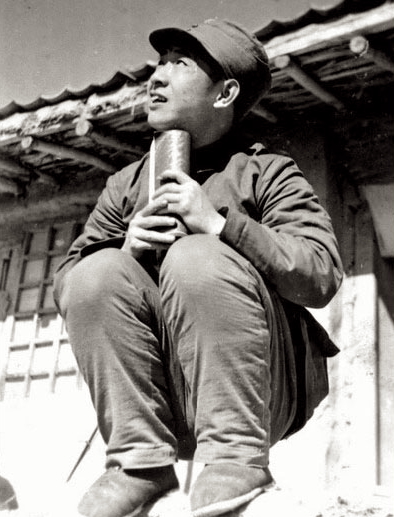

Born into a poor peasant family in Hunan in 1915, Hu joined the Communist Party in 1933, was one of the 8,000 survivors of the Long March of 1934-35 (by Suettinger’s estimation), and was active in the CCP’s base of Yan’an. In 1939 his career took off when Mao Zedong appointed him to an important position in the Central Military Commission’s Organization Department. This is when Hu began his long involvement in Party personnel issues, including intra-Party purges known as “rectification” (整风) campaigns. After the conclusion of the Sino-Japanese War in 1945, Hu partook in many battles during the Chinese Civil War as a political commissar prior to the CCP’s victory over the KMT in 1949. Suettinger’s research of this period is particularly original and he is similarly painstaking in his tracking of Hu Yaobang’s career through the 1950s, when Hu began his long tenure as head of the Communist Youth League.

Like so many other cadres, Hu suffered greatly during the Cultural Revolution. Suettinger takes the reader through the horrors inflicted upon Hu in excruciating detail, including how he was “dragged out for struggle” by Red Guards in 1966, and was the first Central Committee member to be physically harmed as the mass violence unfolded that summer. In August 1966, Hu was:

“attacked by a seventeen-year-old girl who slashed at his head and face with a leather belt, drawing blood. On another occasion during this period, Hu was beaten with wooden poles and for several days he could not stand straight or walk without crutches.”

In December, attacked again, Hu was “thrown to the floor and thrashed with belts by several Red Guards, rolling around screaming in pain.” Hu’s colleague in the Youth League, Hu Keshi, who was punished alongside him, estimates that Hu Yaobang was “beaten ten to twenty times during this period.” Subsequently, in July 1967, Hu was dispatched to an automobile factory for further “struggle sessions” where “workers there beat him senseless, to the point that he could not walk without assistance.” In 1969 Hu was subjected to further maltreatment when he was dispatched to a newly created May 7 Cadre School (五七干校) in Henan province. He was forced to do manual labor, and “on several occasions he collapsed from exhaustion or heat prostration,” also suffering from a prolapsed rectum, painful hemorrhoids, a shoulder ailment and serious back pain.

Suettinger concludes that Hu Yaobang survived this torment and torture because he was “mentally tough, strong-willed, and stubborn.” Having survived six years of physical and mental persecution, in October 1972, at the intervention of Premier Zhou Enlai, he was finally released and allowed to return to his home in Beijing.

Perhaps Hu’s greatest career contribution was in redressing the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, in particular from 1975-78 and 1982-86. During these periods, Hu was the “housecleaner” who did much to correct and clean up the personnel travesties of the Mao era. In 1975, he was suddenly assigned (by Mao’s future successor Hua Guofeng) to the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) — an institution he had no previous experience with, working in subjects he knew little about. Upon his arrival, Hu told the beleaguered staff:

Who am I? I graduated from elementary school and was in lower middle school for half a year. I am basically unsuited, I have no foundation whatever in natural science.

Hu’s appointment, while seemingly obscure, was in fact central to Zhou Enlai’s plans to turn the country from revolution to modernization. Zhou had launched the Four Modernizations program in 1975 at the 4th National People’s Congress. But without a large cadre of scientists and technicians, how was China to modernize? Hu’s remit at CAS was to clean out the Maoist “reds” who had infiltrated the academy and replace them with rehabilitated technical experts, who would be charged with advancing China’s science and technology. Yet he did not stay there for long.

After Mao’s death in 1976, he was appointed Director of the CCP Central Committee’s Organization Department (1977-78), the nerve center of Party personnel management. There, Hu personally oversaw (and accelerated) the professional and political rehabilitation of “more than half a million wrongful Party judgments, … affecting more than four million cadres and their families.” These were mainly cadres who were purged during the Cultural Revolution, including “several hundred cases involving Mao’s personal enemies.”

Hu also played an instrumental role in “uncapping” many of the estimated 547,000 people labeled as rightists during Mao’s Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957. During the Maoist era, the political practice of “capping” meant that those individuals who were targeted for mass denunciations were forced to don cone-shaped dunce hats (帽子) with their “crimes” inscribed on them — subsequently, when the purgees were rehabilitated, their proverbial caps were removed. Suettinger notes that “Hu personally reviewed roughly two thousand petition letters from people of all ranks and backgrounds.”

Perhaps Hu Yaobang’s greatest career contribution was in redressing the excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

Although Suettinger doesn’t discuss it, Hu Yaobang was also instrumental in launching a three-year rectification program — announced in 1982 at the 12th Party Congress — in which 40 million Party members had to re-register and be vetted for their Cultural Revolution activities. This was an effort to root out allies of the Gang of Four, a political faction (including Mao’s wife Jiang Qing) who had engaged in the practice of “beating, smashing, and looting” during the Cultural Revolution. The campaign also weeded out “worker-peasant-soldier” (工农兵) political beneficiaries of the Cultural Revolution, and those with a “low cultural level” (that is, lack of education).

When the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) was established in December 1978 — a new body intended to police Party ranks — Hu was additionally appointed as one of its secretaries, alongside the other revolutionary leader Chen Yun. Again, Hu’s job was to ferret out Party members who lacked expertise.

Hu also made important theoretical and ideological contributions during his brief time as head of the Central Party School (1977) and the Central Propaganda Department (1978-80). In the former capacity, Hu was instrumental in catalyzing Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 campaign to promote the slogan “practice is the sole criterion of truth,” which was launched in the Party School journal Theoretical Trends (理论动态) and became Deng’s ideological justification for a variety of his pragmatic policies that kickstarted the Reform and Opening era. As Deng famously said: “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice it is a good cat.”

Suettinger’s research reveals that Deng sometimes disagreed with Hu, or only provided him with “lukewarm support” — a revisionist interpretation of conventional wisdom. Suettinger also uncovers Hu Yaobang’s ideological struggles with arch-conservative ideologues Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun, as well as Deng himself, over the January 1979 Conference on Theoretical Work Principles, and the protracted drafting of the 1982 text “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China” (this conference and the resolution were major turning points in repudiating the dogmatic Maoist era). But he concludes that “Deng still needed the talents and enthusiasm that Hu brought to his work — superior organizational skills, propaganda resources, and a reputation for probity.”

During the late 1970s, as Suettinger demonstrates, Hu was quite progressive on ideological matters, waging battles with doctrinaire conservatives, and he was instrumental in shaping the post-Mao ideological landscape. It is during this relatively brief period, after Mao’s death, when Hu Yaobang the progressive reformer really emerges. Yet during the Maoist period, Suettinger portrays Hu as a loyal, even sycophantic, cadre who carefully followed — and did not buck — the Chairman’s or the Party line.

The one time when Hu had an opportunity to push back against Mao was from 1961-64, during the period of economic retrenchment and recovery after the disastrous Great Leap Forward and ensuing famine. During this time Mao “retired to the second line,” stepping away from the leadership and remaining mostly outside of Beijing, while other Party leaders including Chen Yun, Deng Xiaoping, Li Xiannian, Yao Yilin and Liu Shaoqi were left behind to clean up the mess. These more pragmatic leaders drafted a series of important policy documents (such as the “60 Articles on Agriculture,” “70 Articles on Industry,” “14 Articles on Science” and “60 Articles on Education”) which served not only as a comprehensive program of economic recovery in the early 1960s, but subsequently became the programmatic basis of the post-Mao Dengist reforms.

This was a golden opportunity for Hu Yaobang to have burnished his reformist credentials — yet there is no evidence of Hu being involved with these pragmatic reformers and policies. This is a real oddity. Suettinger describes this time as a period of “Hu Yaobang on the sidelines,” adding: “Hu Yaobang’s thoughts during this tumultuous period are unknown.” What is known is that, as far as agricultural reform was concerned, the new leadership adopted a “household contract responsibility system” (包产到户), which proved immediately successful in restimulating grain output and overcoming famine conditions. Yet while these pragmatic leaders were instituting this new agricultural system, and the peasantry were eagerly embracing it, Hu Yaobang criticized the reform. Suettinger tells us that, in 1964, “Hu’s first priority was no longer improving production but getting rid of the practice of [the household contract responsibility system],” claiming it had “a dangerous nature.” (In 1981, he traveled to Anhui province and apologized to some of the same cadres, acknowledging that “they had been right, while he had helped lead rural policy down a dead-end road.”)

During the Maoist period, Suettinger portrays Hu as a loyal, even sycophantic, cadre who carefully followed the Party line.

In providing such an exhaustively detailed historical record of Hu’s career, Suettinger has contributed a valuable service to the historical record, scrutinizing arcane information that no historian in mainland China could dream of publishing. In the best Dengist tradition, Suettinger “seeks truth from facts.”

However, the strength of the study is also at times a weakness: the sheer volume of factual detail and empirical data can be overwhelming. Organized chronologically, Suettinger slow-walks the reader through every twist and turn — no matter how minor — in Hu Yaobang’s life and career. The book would have profited from some overarching theses and meta-narratives, drawing out the significance of the data and providing readers with thematic touchstones. It would also benefit from engaging with secondary literature on the topic, contrasting his interpretations with those of established scholars such as Richard Baum, Ezra Vogel and Andrew Walder. But these are relatively minor critiques. Suettinger has written the definitive study of Hu Yaobang’s life and times, and it is a major contribution to our understanding of Chinese communism.

Taking Hu Yaobang’s life and career as a whole reveals not only a progressive reformer — Suettinger’s main characterization — but also that of a tragic figure and victim. The capricious Chinese communist system does not reward cadres who buck the system, but instead punishes them when they stray too far from the Party line or the supreme leader’s dictates. Hu Yaobang may have been a reformer late in his career, or the “conscience of the Party” as Suettinger puts it, but he was too liberal for the rigid conservative leaders and Leninist apparatchiks throughout the Party-state. The system always prevails. This was Hu Yaobang’s tragedy. ∎

Header: Chinese students stage a night sit-in on Tiananmen Square, to commemorate the funeral of Hu Yaobang, on April 22, 1989. (Catherine Henriette/AFP/Getty)

David Shambaugh is a scholar and author of Chinese politics and foreign relations. He is the Gaston Sigur Professor of Asian Studies, Political Science, and International Affairs at George Washington University, where he directs the China Policy Program. He is also a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Shambaugh’s books include a biography of Hu Yaobang’s counterpart Zhao Ziyang, The Making of a Premier (1984).