Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

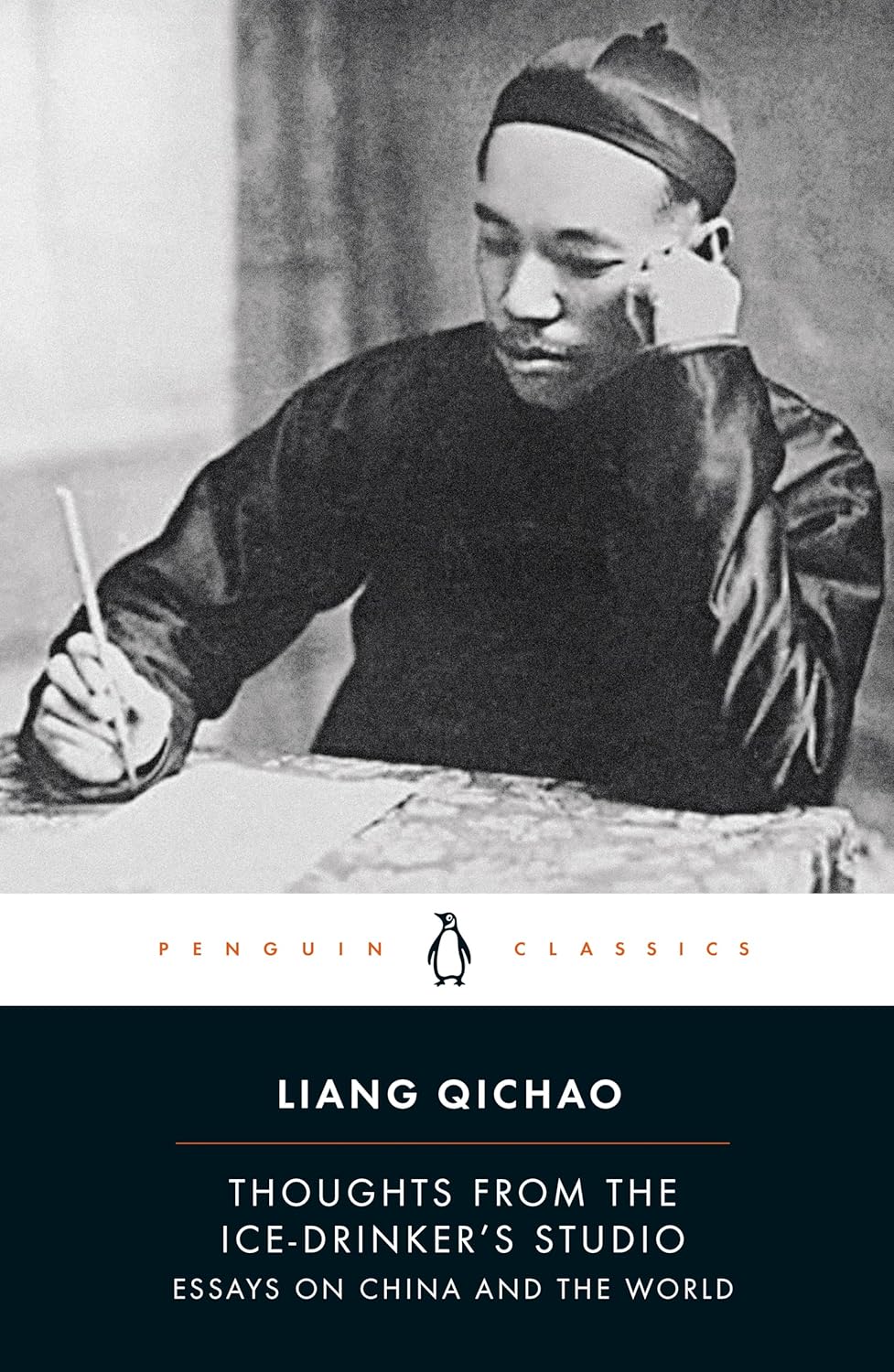

Reviewed: Thoughts from the Ice-Drinker’s Studio: Essays on China and the World, Liang Qichao, tr. Peter Zarrow (Penguin Classics, September 2024, U.S. paperback).

In Taipei in April 2024, I participated in events pegged to dual decennials: that of Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement, which had just passed, and that of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement, which would soon arrive. In the former, student activists occupied a key government building to protest a trade policy they felt would undermine Taiwan’s ability to set a course free from the mainland’s influence. The latter, in which students (and others) occupied Hong Kong’s central business district and two other neighborhoods, was a struggle to democratize the way Hong Kong’s Chief Executive was chosen, so that person would be less beholden to Beijing and the local tycoon class. At one of the anniversary events, Alex Chow, who in his mid-twenties had been head of the Hong Kong Federation of Students and one of the Umbrella Movement’s leaders, recalled traveling from Hong Kong to Taiwan in the middle of 2014 and meeting Sunflower veterans to compare ideas on protest strategies.

I thought of Liang Qichao.

Born in 1873 in Guangzhou, not far from Hong Kong, Liang, like Chow, was also involved in a famous struggle for change in his mid-twenties. A precocious youth, by the age of 11 he was reading Confucian texts at the level expected of a highly capable scholar in their twenties or older, at which time he passed the provincial-level civil service exam. By 25, he was the youngest of the cosmopolitan reformers who gained the ear of the Guangxu Emperor, a ruler just two years older than him. In 1898, inspired by the Meiji Restoration’s transformation of Japan, Liang and his mentor Kang Youwei pushed the Hundred Days Reform with ambitions of shaping the Qing Dynasty into a constitutional monarchy. These dreams were stifled by a palace coup: the Guangxu Emperor was deposed, placed under house arrest, and died of arsenic poisoning in 1908, in gilded captivity. Some key reformers were executed, others went into hiding within China. Liang and his mentor Kang went into exile. Liang escaped to Japan in mid-1898 and made Yokohama, a port city near Tokyo with a well established Chinese community, his main base of operations.

The harsh crackdown in Hong Kong that began in 2020 also led many local activists to flee. For my book The Milk Tea Alliance, I interviewed some of them in North America, Europe and Asia. When I listened to their concerns and dilemmas, I was reminded of Liang Qichao and his contemporary Sun Yat-sen, the revolutionary and eventual founder of the Republic of China. Like Liang and Sun, the Hong Kong exiles lived abroad, fearing that returning to their homeland would mean instant arrest. They talked about founding new organizations and creating new publications, as Sun and Liang did. They forged connections with Hong Kong diaspora groups, just as Liang and Sun connected with the Chinese diaspora during various trips abroad. And they sought out like-minded people from other parts of Asia to learn from and perhaps collaborate with, although the Hong Kong activists saw connections between their struggle and that of Tibet and Thailand, while Liang and Sun learnt from Japanese radicals and Philippine insurgents.

At the time, both Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen were well known in some circles in Asia, and in Chinatowns around the world. In these settings, Liang’s role in the 1898 reforms, and his activity as a writer and founder of publications, gave him a higher profile than that of Sun. Yet Sun held a degree of fame in the West outside of the diaspora, due to the headlines generated when he was kidnapped by Qing agents in London in 1896 and his writing about his brief time as a captive. Over time, as Sun became associated with the successful Xinhai Revolution of 1911 that overthrew the Qing dynasty, his international reputation and name recognition outgrew that of Liang, who was linked only to abortive insurrections. Sun is immortalized in China by an enormous mausoleum in Nanjing, while Liang has little more than a statue in Tsinghua University. Yet Liang’s contribution to modern China — and his legacy for dissidents in exile to come — is just as large, and he deserves to be recognized as one of the most important intellectuals of his era.

When I listened to the concerns and dilemmas of Hong Kong activists, I was reminded of Liang Qichao and his contemporary Sun Yat-sen.

Historian Peter Zarrow’s new translation of Liang Qichao’s writings, Thoughts from the Ice-Drinker’s Studio: Essays on China and the World, seeks to give him a new turn in the spotlight. The work is a collection of Liang’s essays, with an introduction by Zarrow that offers a biographical sketch of the man and examines his political thought, annotated throughout with notes on Liang’s myriad references. The title is a nod to Liang’s pen name, which cast him as so passionate about new ideas and so inflamed by concern for his homeland that he had to drink ice to cool his intellectual ardor.

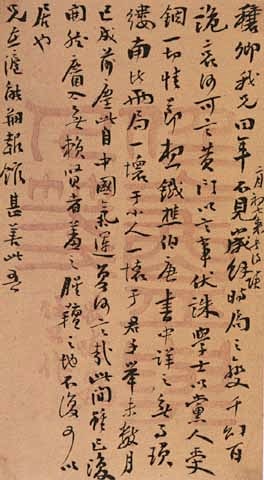

To say Liang was a prolific writer — someone who read widely and was interested in all sorts of topics — is an understatement. He published thousands of short pieces, many of them appearing in periodicals he founded and edited. In these, he often mixed allusions to Confucian texts and historical events with explanations of political concepts, from constitutions and citizenship to nationalism, that were relatively new in China. He became a major influence on a wide spectrum of Chinese thinkers and writers, especially those who spent time studying in Japan. These included Lu Xun, a giant figure in Chinese modern letters who came to Japan as a student in 1902 and became an avid reader of Liang’s publications.

Liang had many writing styles. In the 1902 essay “Renewing the People is China’s Most Urgent Task Today”, he describes a shift from an older imperialism to what he refers to as “national imperialism,” as evidenced by “Germany’s takeovers of Asia Minor and Africa” and “America’s annexation of Hawaii” as well as “Britain’s War on the Boers.” He writes, in Zarrow’s fluid translation:

This national imperialism is different from the past imperialism. In the past, the likes of Alexander the Great, Charlemagne, Chinggis Khan and Napoleon all possessed great ambition, made farsighted plans, aimed to crush the world and swallowed up weaker countries. However, past imperialism all stemmed from personal ambition, whereas national imperialism results from the rising power of a nation. The former was driven by powerful rulers, whereas the latter follows the trends of our times. Therefore, the former’s invasions last but a while, like a violent squall that is over by noon, whereas the latter’s advances look to endure, ever expanding, ever deepening.

Unfortunately, China is trapped in the middle of this vortex. What can it do? If the threat stemmed from just one or two men of ambition, we could resist them with one or two heroes of our own. But facing nations that are following the inexorable trends of the times, there is no way we can resist them without unifying the whole nation … the only course for us is to promote nationalism. And to promote nationalism, the only course is to renew the people.

Liang goes on to call for dramatic moves to raise China’s educational level. As the piece unfolds, his arguments are continually informed by the tenets of Social Darwinism, a common trait in works by Chinese thinkers of the time who often saw nations as being at different stages along an evolutionary spectrum. He focuses mainly on the recent past, but drops in a line by the early Confucian sage Mencius about the need to take timely action to deal with any problem, prodding his readers to view the seemingly impossible task of transforming China into a strong modern nation as both possible and urgent.

Liang read up on, and wrote about, an incredibly wide range of Western thinkers and topics in world history. He had a keen interest in foreign thinkers and international events of his era. He was interested in Plato and Aristotle, both of whom he brings into a 1902 essay in Zarrow’s compendium titled “Public Mortality” that also discusses Confucius, Mencius and the U.S. constitution.

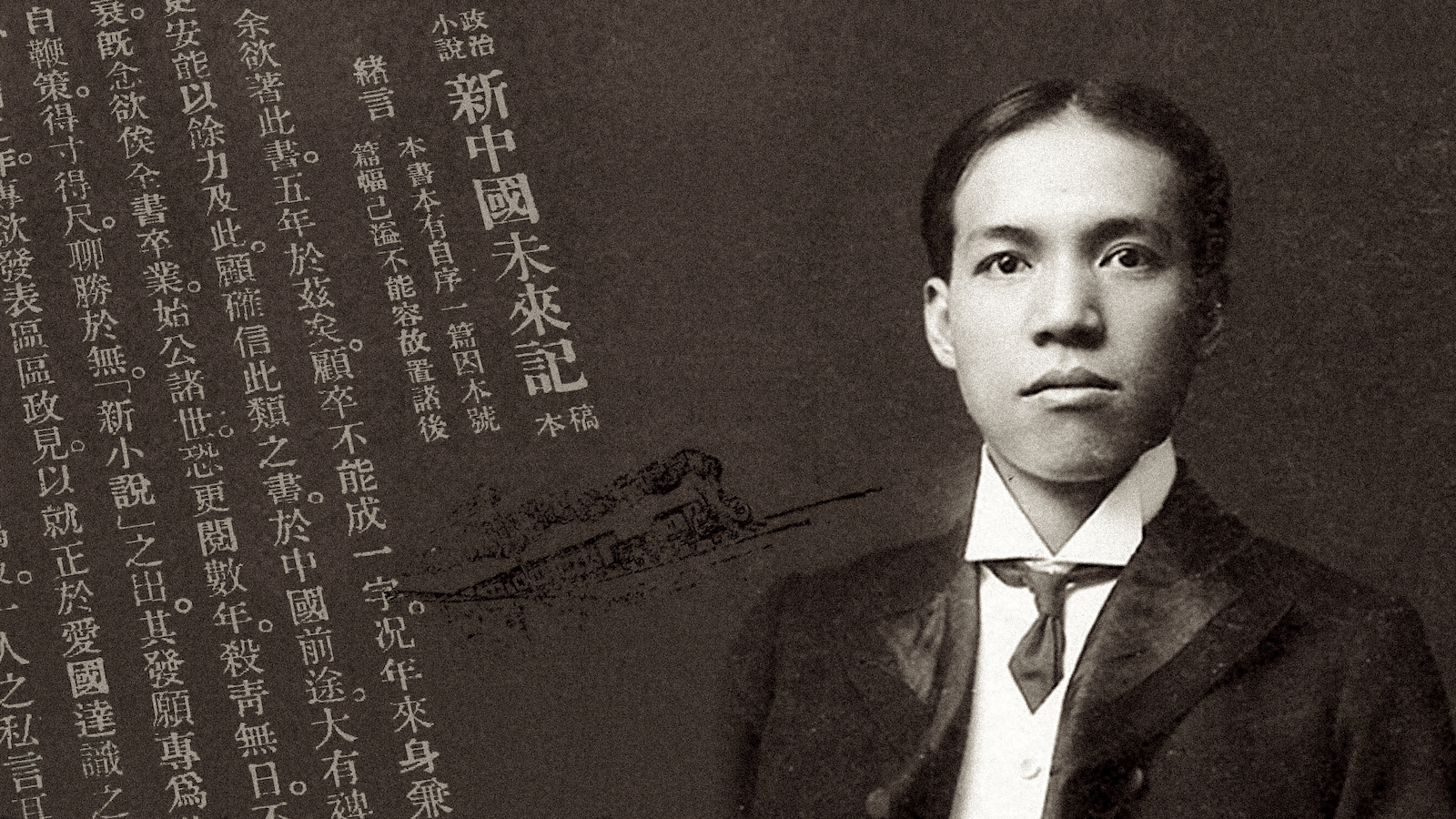

Liang also wrote poems and commentaries that engaged with Buddhism. He had a lot to say about literary issues, including the many European novels he read in Japanese translation. And he even penned an unfinished novel, The Future of New China, that imagines a future when a World’s Fair is held in Shanghai, with a descendant of Confucius playing a central role. (I have often wondered, as have others, what Liang would have thought of the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, or the 2008 Beijing Games.) The novel is often called the first major Chinese work of science fiction — a genre he rated highly, translating Jules Verne’s Two Years’ Vacation and encouraging Lu Xun to translate A Journey from the Earth to the Moon, as a way to increase the average Chinese reader’s scientific knowledge.

Liang’s pen name cast him as so passionate about new ideas and so inflamed by concern for his homeland that he had to drink ice to cool his intellectual ardor.

Liang has been the subject of an enormous amount of academic writing in all languages, and features widely in modern Chinese history textbooks and sourcebooks. He was the subject of biographies by two of the leading Chinese historians trained during the Cold War: Joseph Levenson in Liang Ch’i Ch’ao And The Mind Of Modern China (1953), who called him China’s “most influential turn-of-the-century scholar-journalist”; and Philip C. Huang in Liang Ch’i-ch’ao and Modern Chinese Liberalism (1972). Liang was also the focus of impressive first books by two stars of the cohort of China specialists to receive their doctorates soon after 1989: Tang Xiaobing in Global Space and the Nationalist Discourse of Modernity (1996) and Rebecca Karl in Staging the World (2002).

Yet Liang Qichao’s name is still unfamiliar to most people outside of East Asia. Part of the reason, of course, is that the above books were written primarily for specialist readers. There have been some notable books aimed at general readers in which Liang is a prominent character, including Jonathan Spences’ The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1982), Pankaj Mishra’s From the Ruins of Empire (2012) and Andrew Nathan’s Chinese Democracy (1986). Orville Schell and John Delury also devoted a chapter to Liang in their survey of China from the Qing to the present, Wealth and Power (2012), and he shows up more than once in Tim Harper’s Underground Asia (2021), one of the most acclaimed trade books on Asian history published recently. But Liang is far from well known in the Anglophone world, where few have actually read his work.

Even as my work on the transnational interests of Hong Kong exiles gave me new appreciation for Liang and his intellectual range, engaging with his work invoked a sense of déjà vu. In 2009, I had high hopes that Julia Lovell’s sparkling new translation of Lu Xun’s complete fiction, The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China (Penguin Classics) would make the author a household name in the West, something that previous translations of his work, some of them very skillful, had failed to do. Lovell’s book was well received, but this did not happen. Nor is it likely to happen with Zarrow’s volume on Liang, which has been slow to get review attention. It is valuable in each case to have a compact, engagingly packaged and thoughtfully introduced translation collection of short works by the two writers, to assign in class and recommend to those who want to deepen their appreciation for these towering figures of Chinese letters. Breaking through to household name status outside of East Asia requires an extraordinary event, like founding a new country (as in Sun Yat-sen and Mao Zedong’s cases) or a pop culture connection — such as winning a Hugo award and having The Three Body Problem adapted into a Netflix series, in Liu Cixin’s case.

Liang’s legacy extends through his lineage. His eldest son Liang Sicheng was a notable architect, and his second son, Liang Siyong, was a founding figure of Chinese archaeology. In that respect, Liang is like one of the Western thinkers whose ideas about evolution he helped introduce to Chinese readers, the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, remembered both for his own work and as the grandfather of the novelist Aldous Huxley and the scientist Julian Huxley. Liang’s own granddaughter, Wu Liming, was a professor of urban studies and geography at Peking University and the author of Liang Qichao and His Children (梁启超和他的儿女们, Peking University Press, 2013).

Liang also had considerable influence on future generations of Chinese intellectuals, including those with political views much more radical than his own. During his sojourn in Japan at the turn of the 20th century, which Zarrow rightly focuses on as Liang’s most prolific period, he was read avidly by those who wanted to see the Qing dynasty stay in power but have its emperors share power with elected officials. Republican revolutionaries also took Liang seriously, and tried to work with him in keeping the realm from breaking apart into pieces or being colonized.

After the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, a similar dynamic persisted. Liang was read both by reformers celebrating the end of Qing rule, but also by those who believed that the revolution had not gone far enough, and that further struggles were in order. One such reader was a young revolutionary who would go on to lead the nation: Mao Zedong. Before settling on Marxism-Leninism as the imported theory worth embracing, Mao was interested in various foreign thinkers whose ideas might help cure China’s ills, and Liang’s eclecticism and wide reading appealed to him.

It is common to contrast “reformers” such as Liang Qichao with “revolutionaries” like SunYat-sen and Mao Zedong. When I took part in a comparative revolutions conference in Japan, convened by Professor Hiroshi Mitani in 2022, however, I began to rethink this distinction. I rethought it further when I returned to Japan for a follow up event in 2024 to present about Liang in Tokyo, also visiting Yokohama, where he lived from 1898 until 1912, to look, largely in vain, for tangible traces of his time there. Participating in the two-part conference, titled “The Pen and Sword in Modern Revolutions” changed my sense of how blurry thecategories of reformers and revolutionaries often were in China, long before Deng Xiaoping insisted in 1985 that “reform is China’s second revolution.”

Professor Mitani, a leading scholar of the late 19th century transition to modernity in Japan that influenced Liang Qichao so greatly, is known for his assertion that the events of 1868, usually referred to in English as the Meiji Restoration, should instead be called the Meiji Revolution. His argument is that, though it did not lead to an end of imperial rule, the restoration of Emperor Meiji’s power set in motion changes in Japan’s political order that were dramatic enough that they marked a clear divide between an old and new order that we associate with revolutions. Participants were urged to take it for granted that events which took place in Japan in the 1860s were revolutionary.

If there was indeed a Meiji Revolution, and if Liang viewed it as a model for what needed to be done in China, then might it make sense to treat him as an early Chinese revolutionary, not a reformer? After all, he collaborated multiple times with Sun Yat-sen, even if the more militant aspects of Sun’s approach and Liang’s more moderate one made a lasting partnership impossible. The political and other differences between Sun, who died in 1925, and Liang, who died in 1929, became clear during the final years of their lives, after both returned to China in the wake of the Xinhai Revolution. Sun Yat-sen was briefly the new Republic of China’s first President, from January 1 to March 10, 1912, before the former Qing general Yuan Shikai pushed Sun from power. Liang Qichao was willing to serve in the warlord’s administration, and even spent a term as Yuan’s Minister of Justice from September 1913 to February 1914, while Sun tried to get his revolutionary project back on track, seeing this as especially urgent after Yuan Shikai declared himself China’s new emperor in 1915. From July to November 1917, Liang served as Minister of Finance in the administration of Duan Qurui, one of the warlords who formed a government after Yuan Shikai died one year after his “dynasty” began, but he shifted back to academic and intellectual work during his final years. Ultimately, he was more at home with political thought than political action.

It is common to contrast “reformers” such as Liang Qichao with “revolutionaries” like Sun Yat-sen and Mao Zedong. [But] these categories can be blurry.

For those young exiles today who have tried to effect change in the People’s Republic of China, and now live outside it, the future is uncertain. Will they remain forever in exile, or be able to return home? Will they become reconciled to the old or new order, as Liang Qichao arguably did, or keep struggling for change, as Sun Yat-sen did? At present some of them, such as Umbrella Movement veteran Alex Chow, who is pursuing a doctorate at Berkeley and stays involved with Hong Kong diaspora groups and connected to Taiwan activists, remind me of Liang Qichao in the time before he served in Yuan’s government.

While in exile in Japan in 1907, Liang became friends with Lin Hsien-tang, a Taiwanese independence activist. Four years later, Liang traveled to Taichung, a city south of Taipei, to visit Lin at his home. In April 2024, I followed his footsteps to Taichung to visit the former home of Lin, which has been preserved as a tourist site. Strolling through its ornate rooms and courtyards, I saw plaques and pamphlets detailing the roles that members of the Lin family played in Taiwan’s struggles against colonial control after it was annexed by Japan in 1895. As well as examples of the Lin family’s calligraphic and poetic talents, there were also references to Liang’s visit in late March 1911, on the eve of the fall of the Qing dynasty in China, though Taiwan would not cast off Japanese rule until 1945, and would not democratize until the late 20th century.

Liang Qichao’s successes as a writer, publisher, translator and public intellectual during his time in exile were notable, yet what brought him to Japan was a failed effort to liberalize an autocratic polity through a peaceful process. I was glad to have finally found a place where a visit from Liang Qichao is still remembered as something worth celebrating. And even though Taiwan has many commemorations of Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Republic of China which is still Taiwan’s formal name, I came across no images of China’s first President, or mentions of his name. ∎

Header: Liang Qichao in Japan, next to the Chinese text of the opening of his novel “The Future of New China.” (Creative Commons)

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is a Distinguised Professor of History at UC Irvine, with a focus on modern China. He is the author, co-author, editor or co-editor of over a dozen books, including China in the 21st Century (2010), Vigil (2020) and The Milk Tea Alliance (2025). A frequent contributor to both scholarly periodicals and newspapers and magazines, he was editor of the Journal of Asian Studies (2008-2018), and co-edits the China section of the Los Angeles Review of Books.