We tend to forget that during the 1960s the U.S. officially sent more people to the moon than it did to China. In that era, the “People’s Republic” under Mao Zedong seemed not only other-worldly but quasi-metaphysical, something constructed in the mind based only on whiskers of evidence. China seemed like Shangri-la. My own first in-person glimpse came in fall 1966, when friends in Hong Kong brought me to peer over the colony’s northern border at Shenzhen (then a farming village, now the fourth largest city in China). I counted myself lucky to spot a water buffalo.

Among Westerners, only a few privileged travelers were allowed to enter. Han Suyin, a Chinese-Belgian writer of fiction and memoirs, and Felix Greene, a British journalist (and cousin of the novelist Graham Greene) were among them. To those of us on the outside, thirsting from afar, the words of such writers glowed — not only because of their scarcity but because they were uplifting. They attested that Shangri-la was real. In retrospect, one can blame the authors for not mentioning the rain of executions during land reform in the early 1950s or the immense, mind-boggling famine of 1959-62 — but that would be unfair. Traveling with government guides, they were sealed off from such facts. They took rosy façades at face value — in the same way that I, on the outside, took their rosy words at face value. Our mistakes were similar.

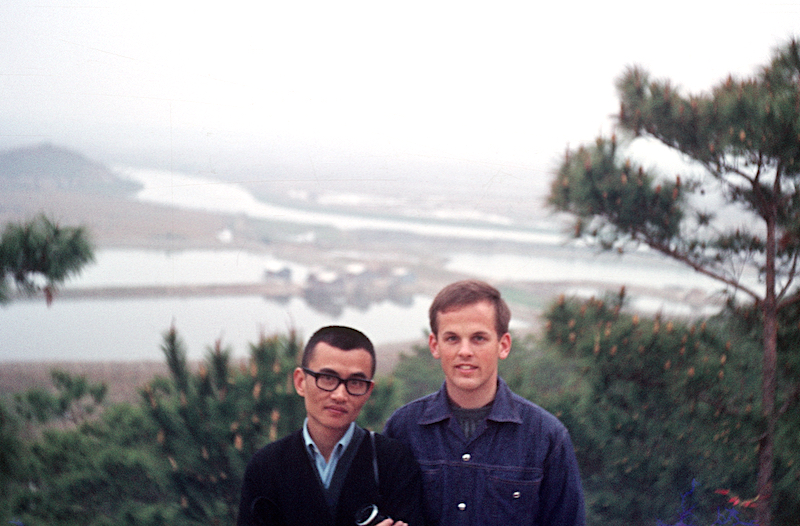

In the 1970s delegation travel to China became possible. I was an interpreter for the Chinese Ping Pong Delegation that toured America in April 1972, two months after Richard Nixon’s ice-breaking visit to China. Beijing offered us interpreters a return trip in May 1973, and we were thrilled. But the month-long journey introduced a few cracks into my image of Shangri-la.

I wondered why rail passengers were segregated by class — “soft sleeper” for officials and foreigners, “hard seat” for everyone else. Our guide explained that “the officials have burdens; they need rest.” Near the city of Tangshan our group descended deep into a coal mine. There, small rail cars scurried through dimly-lit tunnels, but quotations from Chairman Mao, which on the surface of the earth were everywhere, glittering in gold or white letters on bright red backgrounds, were nowhere to be seen. When I asked our guide about this she seemed a bit put off. “Too dirty!” she answered. To me, that was a jolt. The grime in the mines is OK for the workers, but not for the thoughts of their leader?

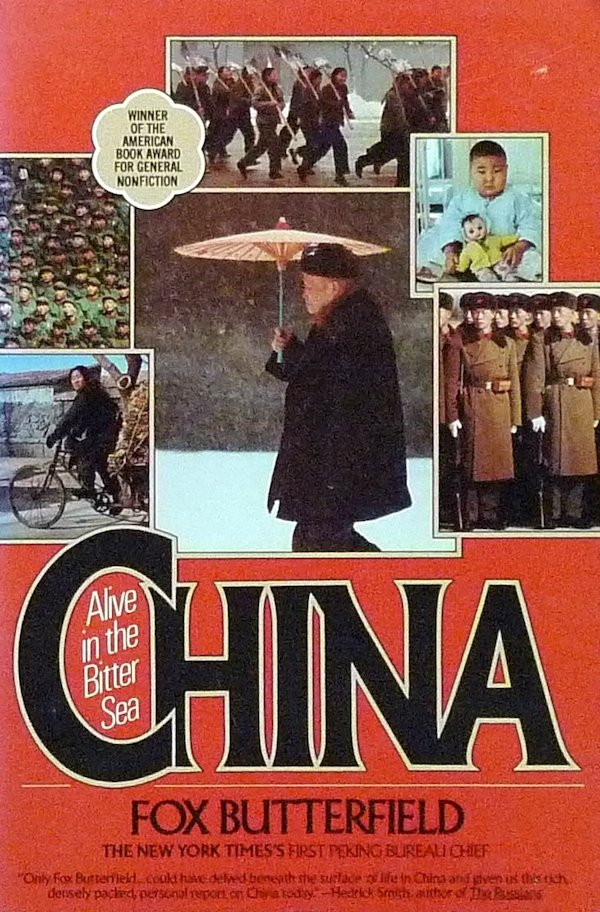

China opened wider during the years after Mao’s death in 1976. Western journalists who worked mostly from Hong Kong could now move to Beijing. Fox Butterfield opened a bureau for The New York Times in Beijing, Richard Bernstein went there for Time, Melinda Liu for Newsweek, and Jay and Linda Mathews for The Washington Post and The Los Angeles Times, respectively. These and other writers produced books that not only went deeper than the China journalism of the Mao era but were much more expansive in scope. For readers, the effect was like moving from street stalls to supermarkets.

In the 1980s Western graduate students and scholars could stay in China for months or full years, using libraries and archives, sometimes even conducting surveys or doing field work. It made an important difference to be able to sink into life. I spent the academic year of 1979-80 in Beijing and Guangzhou, studying contemporary Chinese literature, and noticed that I learned much more in the second half of the year than in the first. That was not unusual. Sinking in paid compound interest.

The early 1980s were when I learned that “dissident” writers (such as Liu Binyan, author of the earth-shaking exposé “People or Monsters?”), although in one sense at the fringes of society, were actually the ones telling the most truth about its core. It was precisely because they dared to address the core that they were pushed to the fringes. Writers who flourished in the mainstream did so by not looking at it.

The shock of the June 4 massacre in 1989 put a temporary stop to Western scholarly exchange with China and made working conditions for international journalists considerably more difficult. During the next two decades, though, under the regimes of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, foreign scholars and journalists returned to China and conditions became more regularized. Journalists grew accustomed to the rules that they had to work under as well as to the ways and the risks of circumventing them. Scholarly exchange moved away from centralized national programs toward ties between individual scholars and their laboratories.

Writers at the fringe were telling truth about the core; writers flourished at the core by not looking at it.

In the Xi Jinping era, which began in 2012, the Chinese side continued its quest to harvest technical know-how from the West, but intellectual exchange in all other areas declined. Xi, a “second-generation red,” came to power well-schooled in the skullduggery one needs in order to rise within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) system, but otherwise narrow of vision, wanting in charisma and educated only to the junior-high level (his post-secondary degrees were on paper only). He felt that the national situation he inherited from Hu Jintao was sufficiently precarious that he needed to do something. But what? Unable to envision other alternatives, he turned to the only model he knew, which was the Mao model. (His only significant departure from Mao’s ideology has been his claim to represent the great and ancient Chinese civilization.)

And so it happened that the trappings of a Great Leader fell again upon the Chinese people. Power was re-concentrated into the hands of a single man while panoply and verbiage that idolized the supreme leader returned: Xi Jinping Thought, Collected Works, a New Era, “Core” leadership and so on. Earlier this year the National People’s Congress elected Xi to a third term by a margin of 2952 to 0. Even the rhythms of slogans from the Mao era were resuscitated. (Lin Biao’s famous 1967 instruction to Red Guards, “Read Chairman Mao’s Works, Obey Chairman Mao’s Words, Carry Out Chairman Mao’s Directives” returned verbatim — only with “Xi” now replacing “Mao”.) For Western China watchers the turn back toward Mao was magnified by how they themselves were treated: visas denied, travel constrained, informants intimidated. Are we circling back to where we started?

We are not. Western writing about China is quite different now. A few writers (Daniel Bell and Martin Jacques come to mind) still consistently figure out how to defend Beijing, despite the intellectual contortion that the exercise requires. But even they do not gaze toward Xi Jinping with the sense of wonder and awe that Mao Zedong inspired 50 years ago. Today, a Westerner might feel frustrated to be denied a visa; back then, the very thought of one glowed in the dark like the tail of a firefly. In those days information arrived from China in drips; now information and online commentary are a roiling river.

But more important, China itself has changed. In Mao’s day, information in all public media (blackboards, loudspeakers, meetings, radio, magazines, school curricula, books) flowed unidirectionally from the top down. An individual’s “platform” was limited to the reach of his or her unmicrophoned voice and in the worst of times, it was dangerous to say what one thought even within family. Today, there are internet and messaging platforms galore, and you can mock Xi Jinping at will so long as you do it privately and without an organization. But at the same time, the Communist Party has invested immensely to monitor and intimidate people electronically, and the result might eventually become (who knows?) an asphyxiating technofascism that exceeds even what George Orwell imagined. I am not arguing that things are rosier now, only that they are different.

Consider this example: on March 5, 1970, teachers in Beijing were instructed to bring schoolchildren to the Workers’ Stadium in Beijing’s Chaoyang district to witness the execution, by bullet to the back of the head, of Yu Luoke, a 27-year-old writer who had dared to criticize the Communist Party. On June 15, 2023, in that same stadium, an 18-year-old Chinese soccer fan ran onto the playing field to embrace the Argentinian star Lionel Messi. Pursued by security, the youngster circled the field, outrunning the less fit agents. The crowd cheered him on, chanting “niubi! niubi!” (roughly, in English, “fricking awesome!”). In no dream could a crowd in the Mao era have done that.

Xi and Mao both sought uniformity of thought, but achieved very different results. Under Mao, people usually believed what they were shouting; under Xi, they are often protecting their interests through outward performance. In 2002, Liu Xiaobo wrote a pungent essay, “A Nation that Lies to Its Conscience,” in which he observes how Jiang Zemin drew on Maoist language to enforce society-wide “unity” against Falun Gong. Jiang achieved the unity only in appearance, but that was all he needed. From the ruler’s perspective, a populace afraid to say that it does not hate Falun Gong is just as good as one that does hate Falun Gong. Liu ends his essay asking which is more frightening — a regime that imposes uniform thought or one that demands uniform lies?

Is Xi Jinping aware that his popular support is, in Liu Xiaobo’s sense, hollow? There can be no doubt that he is. Why else would his government spend enormous sums of money on “stability maintenance” that includes fine-grained monitoring of people, however peaceful, whose ideas might — just might — challenge its power? Xi’s insecurity is as visible at the top of his power pyramid as at the bottom. Does a leader who has confidence need to stand at the center of resplendent panoply and declaim “I am confident!”?

In the seventies, the very thought of a visa glowed in the dark like the tail of a firefly.

Still, there are some constants between 1949 and now. For both Mao and Xi, the Party’s grip on power, and their own grips on personal power, have been the highest priorities. Ideology, the economy, Taiwan, historical legacy and other issues are secondary. This priority will not change; it is an axiom of the system.

Constant, too, is a condition of the society that foreign observers seldom notice even though it is huge and has always been present. It is that people’s lives are filled with quotidian concerns — food, family, health, the weather and so on — not Xi Jinping Thought, the wicked Falun Gong or the like. When an ordinary citizen does have a political thought, it is more likely to be about how to handle bullying by a local official. The seam that separates the bottom-up lives of people and the top-down interests of the state was present in Mao’s China and has remained present ever since.

The seam also exists in individual minds, from those of ordinary people to those of the highest officials. The two questions “How do I perform properly within the system?” and “How do I get what I want?” seldom have the same answer. The two modes of calculation exist in parallel, and with time and custom, their co-existence comes to seem utterly normal.

Far too often, Western writers on contemporary China have passed along the official language of the CCP as what “China” wants or thinks. In Henry Kissinger’s 630-page book On China, it is hard to get a sense that the author even knows that indigenous thought in China exists, let alone what it contains. The covers of other recent books by Westerners often advertise that their authors have lived in China for years or have made dozens of trips there — and yet, usually, the writing inside looks only at one side of the seam. As the Chinese cliché puts it, the authors “scratch the itch from outside the boot.” Of course it is better for a China analyst to travel to China than not to, but the frequent failure to get inside the boot suggests that more than visa denials are barring the way.

Language is a major barrier. Books on China are often written by analysts — Kissinger is not alone here — who read only in English translation and do interviews through interpreters or with English-speaking Chinese officials. A world of difference is made for China watchers who can listen, read, speak and think in Chinese. We might ask who gets closer — the writer in Beijing interviewing in English or the one in New Zealand reading in Chinese? Since the 1950s, the Western China watchers who have been best at “crossing the seam,” so to speak, have been good at Chinese language. Father Laszlo Ladany — whose newsletter China News Analysis appeared between 1953 and 1982 — scoured the official Chinese press and, as the writer Wu Zuxiang put it, could read it “upside-down.” If Ladany read that heroic PLA soldiers rescued 13 miners near Hefei, he knew there had likely been a catastrophic mine collapse near Hefei. Later Simon Leys, followed by Geremie Barmé and Michael Schoenhals, showed how entering the world of Chinese language could make very large differences. In his new book Sparks, Ian Johnson writes entirely from the indigenous side of the seam.

Since the late 1980s, China watching in the West has underused the native-Chinese talent that has resided abroad. Miles Yu, who recently served as principal China policy and planning adviser at the U.S. Department of State, was the first and so far only exception within the U.S. government. Before him, exiles from China such as Liu Binyan, Hu Ping, Su Xiaokang and Yan Jiaqi were almost entirely overlooked by American government and journalism. Part of the problem was that their English was limited. The other part was that the China watching field, whose culture has been dominated by English-speaking scratchers-of-the-boot, did not welcome them.

The growing attention paid to publications such as Xiao Qiang’s China Digital Times, and to such fluid writers of English as Zha Jianying, Fan Jiayang, Cheng Yangyang and others give us hope that this bias may be on the way out. The English-language fiction of Ha Jin, although imaginative in part, gets us deep into the region on the other side of the seam — as do translations of the autobiographies of Ai Weiwei and Fang Lizhi. Writers who come out of Chinese culture pick up on things that Westerners miss. The Song poet Su Shi had a point when he wrote, “When the river turns warm in spring, the ducks are first to know.”

I doubt that the Chinese people mentioned in the previous paragraph would feel very comfortable with the label “China watcher.” The term suggests a view from a distance and one that concentrates on government policies, but it is precisely transcendence of that viewpoint that makes culturally-imbued Chinese views so valuable. The terms “China expert” and “China analyst” have similar problems, to say nothing of “old China hand” (which was still alive when I first went to Hong Kong in 1966). When Chinese people refer to a Westerner as a zhongguotong (中国通), “one who knows China through and through,” the point is almost always ironic. It is either a gentle put-down or a joke. Everybody knows that it is impossible for a Westerner to get to the bottom of knowing China.

Far too often, the official language of the Chinese Communist Party is passed along as what “China” wants or thinks.

While reviewing six decades of China writing by Westerners, we might also note how Chinese views of the West have shifted. In 1950, with the Korean War, Mao launched a “Resist America and Aid Korea” campaign, and in the years that followed he continued to denounce American imperialism. Yet it is unclear how deeply that attitude sank into ordinary Chinese life. Beginning about a hundred years before then, America had already been meiguo, “the beautiful country.” The term originated not from the idea of beauty but because of the second syllable in the word America, but homonyms carry weight in Chinese culture, so the sound itself was a fortuitous start for the American image. Moreover, by the late 1970s the U.S. had become the go-to example in China of what “modernization” looked like. In the 1980s I had to work hard to persuade young Chinese that the U.S. had flaws.

In recent years a tide of anti-Americanism has appeared. Some of it is state-sponsored. Two decades ago the CCP began paying people “fifty cents” (half a Chinese yuan) for each anti-American comment posted on the Internet. Prisoners could earn perks and even early release for such work. But other anti-Western vitriol, based in a feeling of national pride and of rivalry with (not hatred of) the West, is heartfelt. An example was the nationwide uproar last April after BMW employees, at a car show in Shanghai, were caught on videotape apparently giving free ice cream to foreigners but not to Chinese.

At a deeper level, some Chinese intellectuals who had long seen the U.S. as a model for democracy have felt some disillusionment. The insurrection at the U.S. capitol on January 6, 2020, made the foundations of American democracy seem less iron-clad than before, and the insistence on political correctness pressed by an elite reminded others of the Cultural Revolution. An external pressure that said “you have to believe X and if you don’t you need to look inside yourself to find the reason why and then confess and then correct yourself” was chilling.

In short, Chinese views of the West during the post-Mao years have sometimes been as blinkered as Western views of China. Both sides have drawn too much use of their own contexts as they look across oceans at the other. But this is natural, and we should not be discouraged. Western writing on Communist China, while still flawed, is immensely better today than it was sixty years ago.

The moon has regained its lead as the lesser-known terrain. ∎

Images courtesy of the author.

Perry Link is Professor of Comparative Literature/Chinese at University of California, Riverside, and Professor Emeritus of East Asian Studies at Princeton University, specializing in 20th-century Chinese literature. His publications include The Uses of Literature (2000), An Anatomy of Chinese (2013) and, most recently, I Have No Enemies (2023). He is a regular commenter on Chinese society and politics, at The New York Review of Books and elsewhere.