Reviewed: I Have No Enemies: The Life and Legacy of Liu Xiaobo, Perry Link and Wu Dazhi (Columbia University Press, 2023)

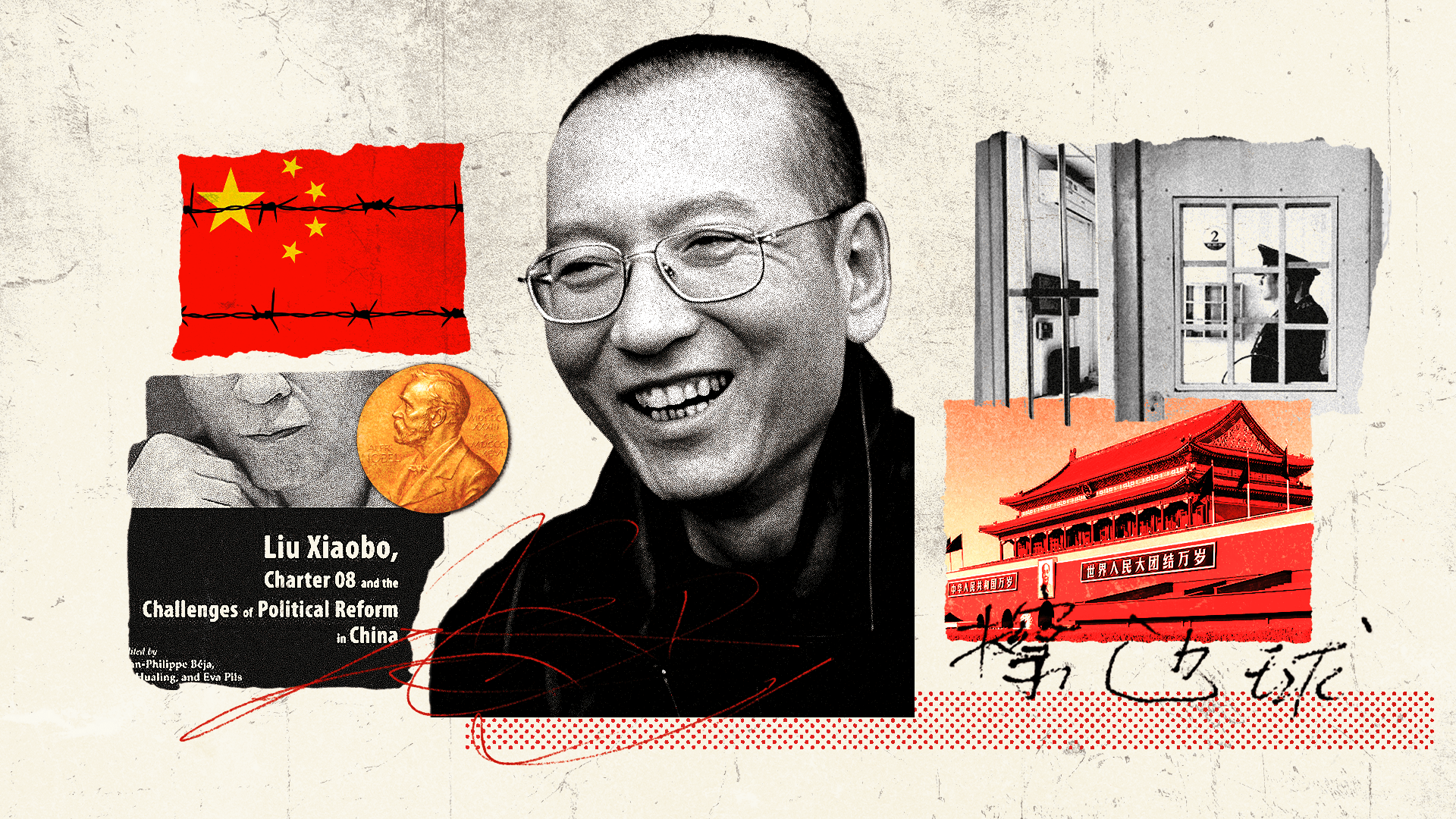

When Liu Xiaobo died in 2017, he had become China’s most fiercely principled and iconoclastic public voice. Possessing an almost allergic reaction to autocracy, he ardently opposed the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s rule and hoped passionately to see his country become a more open, humane and just place. His life and work are reminders that despite the well-manicured exterior of political life that the CCP tries to project, its despotic political system has generated deep wellsprings of opposition to its Leninist state. Although difficult to measure, sometimes even to see, these wellsprings have pooled over the last century to form subterranean aquifers of dissenting thought that keep surfacing.

During my many decades of studying and writing about China, I’ve digested thousands of novels and works of non-fiction in the field. But I cannot think of a book about contemporary Chinese political thought that has so drawn me into the narrative of one thinker’s life as I Have No Enemies: The Life and Legacy of Liu Xiaobo (2023, Columbia University Press) by Perry Link and Wu Dazhi — the latter a pseudonym adopted to avoid a punitive response from the CCP for deigning to research such a politically sensitive topic. A definitive biography of Liu’s life, based on the authors’ meticulous research, it offers readers an illuminating tour of China’s intellectual underbelly, while at the same time infusing the period of contemporary Chinese history in which Liu lived with a deeply human dimension.

The title shares a quote — “I have no enemies, and no hatred” — with a previous collection of Liu’s essays and poems, No Enemies, No Hatred (2013, Harvard University Press), that Perry Link edited along with Tienchi Martin-Liao and Liu Xia. Now, ten years later, Link and Wu have given us a full narrative of Liu Xiaobo’s life, his intellectual journey, and his death while still in detention.

Liu Xiaobo’s life and work are reminders that despite the well-manicured exterior, China’s despotic political system has generated deep wellsprings of opposition to its Leninist state.

Liu Xiaobo was born in the Manchurian city of Changchun in 1955 into a family where, like Mao Zedong, Liu found himself constantly at odds with, and regularly beaten by, his tyrannical father. Growing up in such a state of antagonism seems to have steeled him to bear, and sometimes even to embrace, such adversity.

During the Cultural Revolution, he went with his parents to inner Mongolia before being “sent down” (下放), alone, to rural Jilin province as an “educated youth” (知识青年). However, when Mao died in 1976 and Deng Xiaoping returned to power two years later, he began studying Chinese literature at Jilin University. Already a voracious reader, a lover of poetry and philosophy, and a polymath, Liu was becoming an increasingly iconoclastic, even nihilistic, thinker. At the same time, he was developing a preternatural urge to find new answers to vexing social and political questions in China.

In 1982 Liu went to the capital to become a graduate student at Beijing Normal University, and later was a lecturer there. This was during the exciting, if uncertain, 1980s when almost every aspect of life in China, from economics to politics, was opening up in ways that invigorated Liu. He was an ardent supporter of Deng’s “reform and opening” (改革开放) policies, and felt a new idealism and hope for the future. As Link and Wu observe, during the mid-1980s intellectuals such as Liu “felt as if they were emerging from an uncorked champagne bottle.” Liu’s first wife, Tao Li, described him then as “a spark of life that had just begun to burn.” He also matured quickly as a thinker and writer during this time when vigorous public discourse brought new surprises almost every day in terms of what could be thought, written and said in public.

“At junctures in human history where societies have improved,” Liu wrote in 1983, “the differences have been made precisely not by people with balanced views, but by ones who are passionate about moving in radical new directions.” By 1986, he had turned into an iconoclast, writing: “The readiness to rebel, intrinsic to sensory life, is the eternal and limitless force by which sensory life deals fatal blows to rationalist dogmas.”

By 1988, he had become even more outspoken, writing:

To be quite honest, no matter how vicious a tyranny may be, people should not be scared, nor should they complain; all must decide whether they will subject themselves to it or rebel. Whenever the Chinese start heaping scorn on authoritarianism, they should be blaming themselves instead. How could things have reached their present state, where the most outrageous things are taken for granted, if it weren’t for the Chinese being so weak-willed and ignorant? Tyranny is not terrifying; but what is really scary is submission, silence, and even praise for tyranny. As soon as people decide to oppose it to the bitter end, even the most vicious tyranny will be short-lived. The only thing that is worthwhile is one’s own choice and the decision to accept the consequences of that choice.

That same year he told a Hong Kong magazine:

There should be room for my extremism … I’m pessimistic about mankind in general, but my pessimism does not allow for escape. Even though I might be faced with nothing but a series of tragedies, I will still struggle, still show my opposition.

Struggle he did, always painfully aware of the consequences of such outspokenness. “If you’re already aware of how pitiless the autocrats are and you know that any opposition to them will only be getting disaster to fall from the skies, and still you go ahead and bash your head against a brick wall, then you’ve got no one to blame but yourself, if you split your head open,” he wrote in 1987. “If you want to enter hell, don’t complain of the dark; you can’t blame the world for being unfair, if you start on the path of the rebel.”

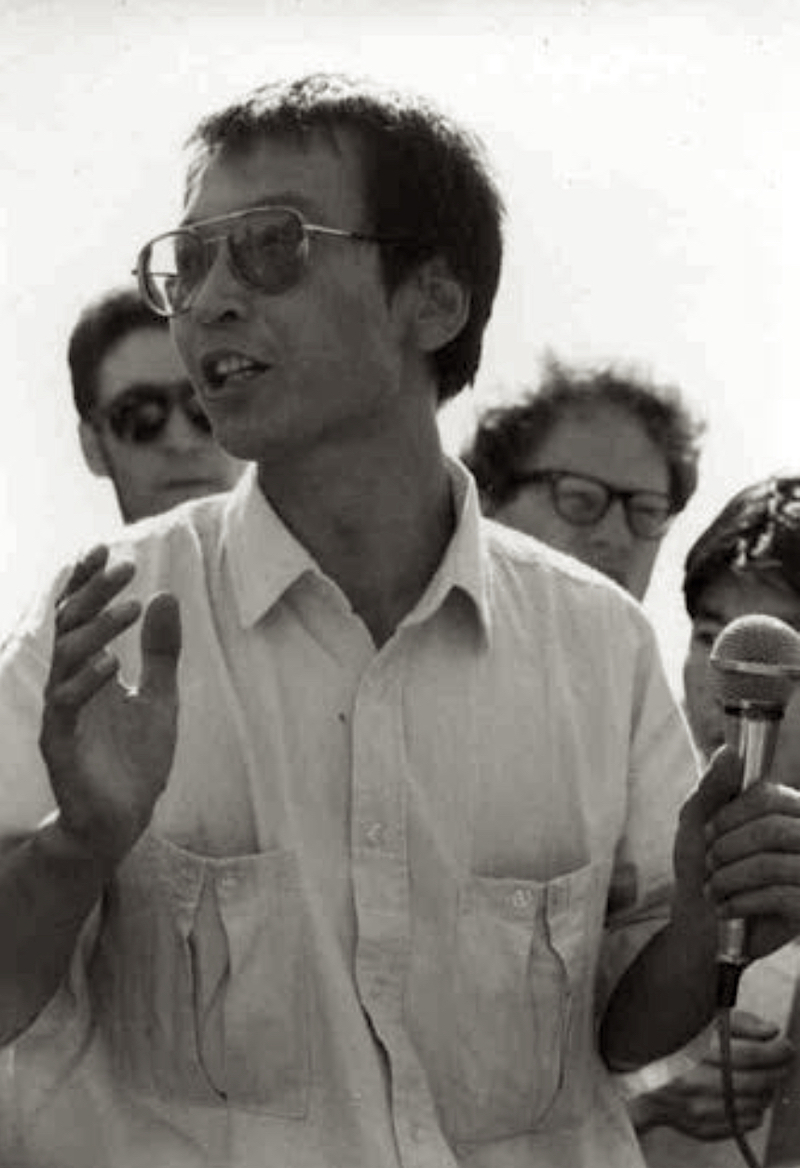

Liu’s was one of China’s most resonant voices, even with his stutter: an enfant terrible whose directness both enthralled and repelled the salons of Beijing’s rejuvenating cognoscenti. Because of his tendency to attack not just the Party but established Chinese intellectuals — compromised by their desire to remain in the good graces of officialdom — Liu was viewed as an unpredictable “dark horse,” but someone worth listening to. He dared utter political thoughts so heretical that few others dared even think, much less articulate, them.

Never reluctant to beard the communist dragon, Liu even extolled Hong Kong’s century and a half of British colonialism as the reason it had been so successful. As far as mainland China was concerned, he mockingly hazarded, “I don’t even know if three hundred [years of colonialism] would be enough.” As more probing and provocative essays poured forth from his pen, the critic Wu Liang referred to him as the “Liu Xiaobo tornado.”

At junctures in human history where societies have improved, the differences have been made precisely not by people with balanced views, but by ones who are passionate about moving in radical new directions.

Liu Xiaobo

My Chinese-born wife, Liu Baifang, and I became acquainted with Liu during the heady late 1980s, while China was still in a hopeful state of flux. He was something of a man about town, always frank and never averse to a little intellectual bomb-throwing.

In the spring of 1989, when student demonstrations broke out in Tiananmen Square, Liu was in New York, due to join a conference of dissident intellectuals and artists I was organizing in California with the scholar Geremie Barmé and my wife. Believing that Chinese intellectuals too often “just talk” but “do not do,” Liu instead jumped on a plane and returned to Beijing. He was drawn by the political energy of the gathering protest movement and he went to Tiananmen almost every day. Although he never became a movement leader, he did join the hunger strike at its end, wrote stirring statements of support, and helped arrange a dramatic exit for students just as the massacre was unfolding on the night of June 3.

One of Liu’s statements on June 2 began: “We announce a hunger strike. We protest, we implore, we repent. We seek not death, but to live true lives.” Calling “the democracy movement we see today unprecedented in Chinese history,” he advocated “the spread of democracy in China through peaceful means,”and declared that “we oppose violence in any form.” He also chastised the government’s response to the protests:

The almost unimaginable stupidity of using martial law troops to repress students and citizens who are protesting peacefully has set an utterly deplorable precedent in the history of the People’s Republic of China. It brings tremendous shame to the Communist Party, the Chinese government, and the army, and it wrecks in a single blow ten years of reform and opening.

Despite the fact that this statement declared a commitment to non-violence, and that Liu had not played a key role in the seven weeks of demonstrations, the authorities, write Link and Wu, “selected Xiaobo to be the primary vehicle in their campaign to tarnish the student movement.” Despite his heroic effort on the night of June 3 to convince students to leave the square and avoid bloodshed, he was accused of “spreading propaganda to incite counter-revolution,” fired from his teaching position at Beijing Normal University, charged as a “black hand” (黑手) who helped to precipitate the demonstrations, and sent to Beijing’s notorious Qincheng prison.

Before 1989 and his first prison experience, Liu was often pretty full of himself. He was not yet in possession of the self-reflective humility that endless surveillance, successive imprisonments and a failed marriage later instilled in him. His interrogators “put a great premium on psychological methods: how to dismantle people’s dignity, lead them into mental traps, and even induce psychological collapse,” the authors tell us. They were especially skillful at mustering what the Czech writer Milan Kundera called an “auto-culpability machine:” a psychological syndrome that mobilizes doubt, guilt and self-recrimination to convince political prisoners to accuse themselves of wrongdoing.

Subject to such psychological manipulation in prison, Liu wrote a confession that he regretted for the rest of his life, and which reads almost like a Christian repentance. Noting that “culturally I favored national nihilism and complete westernization,” he declared:

Solely for my personal satisfaction, and in defiance of the advice of friends and relatives, I charged bullheaded into turmoil. I stirred things up at Tiananmen with another hunger strike right when they were beginning to settle down. I turned ebbing turmoil into a counter revolutionary riot.

He also told a China Central Television (CCTV) interviewer that “I did not see the troops fire their rifles at the masses” (a true statement, as he had not witnessed the slaughter firsthand). The Party grabbed onto these confessions and used them relentlessly against him and the democracy movement.

Liu immediately regretted the optics of his confession. He was one of China’s most respected dissidents, but now he had handed the Party a mea culpa to help them counter the tidal waves of bad publicity sweeping the world in the wake of the massacre. Liu was deeply embarrassed, and when his first wife, Tao Li, divorced him in 1989, he was only undermined further by self-doubt and remorse. “The pain I felt in receiving the divorce papers was entirely deserved,” he acknowledged. But, he added in his newly self-reflective mode, “it was far less than Tao Li’s pain.”

Before 1989, Liu was often pretty full of himself. He was not yet in possession of the self-reflective humility that surveillance, imprisonments and a failed marriage later instilled in him.

Liu was released from prison in 1991. But his confession, which he viewed as an embarrassing breakdown of his moral compass, left him overcome with regret and prone to self-flagellation. The experience also seemed to have awakened him to his own tendencies toward arrogance and an excess of pride. He now began calling for things to be settled through reasonable dialogue and compromise, rather than you-die, I-live confrontation. This catalyzing of a greater humility, maturity and self-reflection proved an important inflection point in Liu’s life.

Despite his contrition, Liu was no less vocal than before. In the relative openness of the Jiang Zemin era in the mid-1990s, he wrote ceaselessly and signed many open letters and statements. One such statement was entitled: “Lessons Written in Blood Press Us Towards Democracy: An Appeal on the 6th Anniversary of June 4th.” Liu may have “repented” in regard to his own shortcomings, but he had not abandoned his dedication to justice, tolerance and freedom of speech. So, of course, the Party continued to surveil and monitor him closely.

And, sure enough, in 1995 Liu was detained again, this time for eight months of so-called “monitored residence” (监视居住). Then in 1996, because he had signed a statement advocating greater dialogue with Taiwan, he was sent away for three more years, charged with “disturbing social order” and shipped off to Dalian for “reeducation through labor” (劳动教养), a form of extra-judicial detention that the authors describe as “handled entirely outside the law with no charges, no paperwork, no procedures, no sentence.”

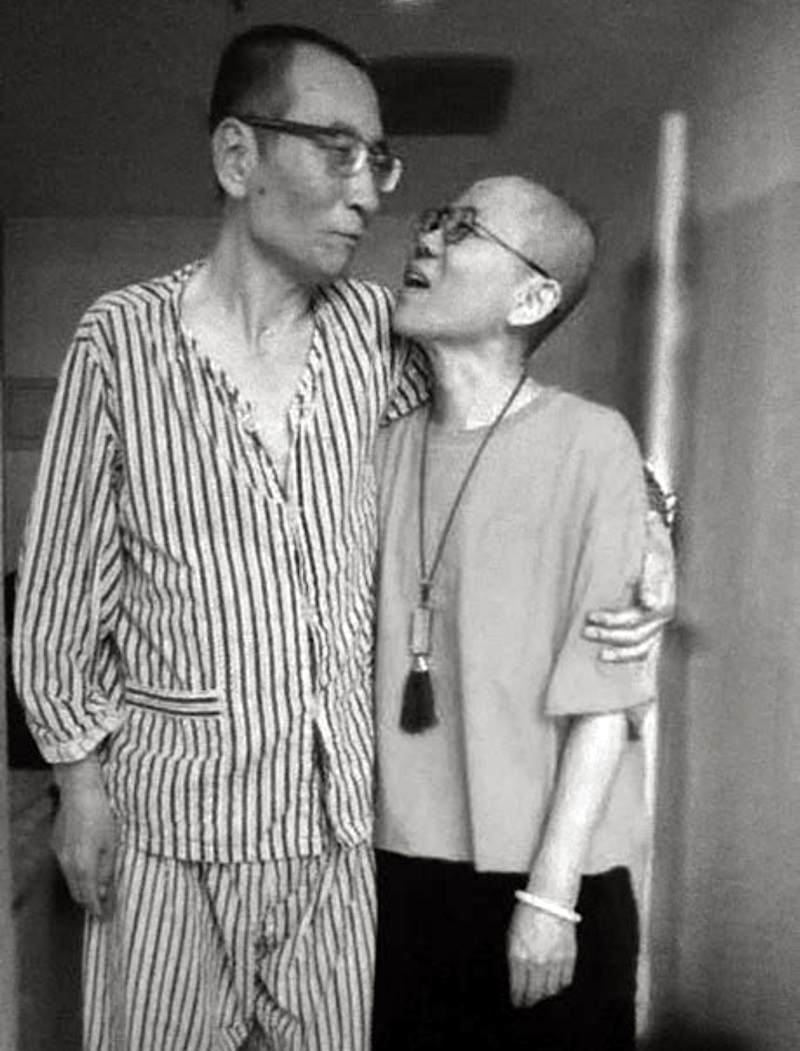

While being “reeducated,” he remarried. His new wife, Liu Xia, was a like-minded but idiosyncratic woman, who was not only also rebellious, but came from a family whose patriarch had been dubbed a “historical counter-revolutionary” (历史反革命) by the Party. Until Xiaobo’s death, Liu Xia — who now lives in Berlin — was his soulmate and Rock of Gibraltar.

Released from labor camp in 1999, Liu Xiaobo’s dramatic life was becoming divided by his repeated imprisonments like the acts of a play. But whereas so many incarcerations would have chastened most people, they galvanized Liu to press on. They were further proof to him that the Party, and its increasingly well-funded and rejuvenated autocracy, must be either reformed or even eliminated before China could transform itself into a more normal, pacific country that respected the rights of all its people, not just those who had the right class background or who were obedient to its dictatorship.

Although out of prison, Liu remained banned from publishing. So, in the early 2000s he turned to the burgeoning platform of the Internet, a vector that he likened to a “magic engine.” “I can attest that the contributions of the Internet to freedom of expression in China have been immense, indeed, hard to overstate,” he effused in the 2006 essay “Long Live the Internet”. But he also observed: “The Communist regime, always obsessed with media control, has been frantic to keep up with Web users [because] dictators always fear information and freedom of speech.”

Influenced by the likes of Václav Havel, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Liu now adopted a tactic of “drop by drop” gradualism, that would not provoke the kind of “strike hard” (严打) counterattack from the state that would destroy both him and China’s fragile democratic movement. Under the new leadership of Hu Jintao, appointed General Secretary in 2002, the Party still had a limited tolerance for opposing views. Never one to trim his jib to censorship, Liu continued to push the edges of these ever-shifting lines of the Party’s political tolerance. In a series of essays penned for the journal Beijing Spring in 2003, he insisted “power resides with officials, but moral conscience with society.” Nonetheless, he urged supporters of democracy to avoid being too confrontational and instead “respond to hate with love, to prejudice with tolerance, to arrogance with humility, to degradation with dignity, and to violence with reason.”

Liu Xiaobo’s dramatic life was becoming divided by his repeated imprisonments like the acts of a play.

In 2003 Liu was also elected President of The Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), a chapter of PEN International founded in 2001. He was also instrumental in the foundation of the Rights Defense Movement (维权运动), a civil rights effort comprised of lawyers and writers. In a 2006 essay, “To Change a Regime by Changing Society,” he wrote: “Short of attempting to take over political power, the non-violent Rights Defense Movement can work to expand civil society and thereby provide people with space in which to live in dignity.” Despite living in a repressive Leninist state, Liu was trying to find non-violent pathways for China to become more democratic and humanistic, because he still hoped that gradual, peaceful change might be possible.

Alas, such hopes proved naïve. For if the Party feared anything as much as outright regime change, it was slow evolutionary political change — what they called “peaceful evolution” (和平演变) — that it saw as sharing the same subversive goal (namely, easing them out of unilateral power). “The Chinese Communist regime has replaced the Soviet Union as the blood-transfusion machine for tinhorn dictators,” wrote Liu in 2006. “The only way to rid the world of the pernicious effects of the rise of the Communist Chinese dictatorship,” he concluded, “is to help the Chinese people transition to a free and democratic nation.”

In December 2008, Liu published “Charter 08,” a statement of principles inspired by Václav Havel’s anti-Soviet “Charter 77” in Czechoslovakia, that called for free expression, the end of one-party rule, an amended constitution, a democratically elected legislature, and an independent judiciary. The manifesto was signed by 303 sympathetic Chinese intellectuals and became one of the first public calls for democracy since 1989. Its opening read:

After experiencing a prolonged period of human rights disasters and a tortuous struggle and resistance, the awakening Chinese citizens are increasingly and more clearly recognizing that freedom, equality, and human rights are universal common values shared by all humankind, and that democracy, a republic, and constitutionalism constitute the basic structural framework of modern governance. A ‘modernization’ bereft of these universal values and this basic political framework is a disastrous process that deprives humans of their rights, corrodes human nature, and destroys human dignity. Where will China head in the 21st century? Continue a “modernization” under this kind of authoritarian rule? Or recognize universal values, assimilate into the mainstream civilization, and build a democratic political system? This is a major decision that cannot be avoided.

The Party felt threatened by this clarion call and obliged to respond. Thus began the final act of Liu Xiaobo’s long and heroic, if tragic, journey.

Liu was, of course, already under heavy surveillance. On December 8, 2008, he was detained by police once again, this time for “inciting subversion of state power.” In his essay “I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement,” intended to be read at his trial, Liu wrote:

I have no enemies, and no hatred. None of the police who have monitored, arrested and interrogated me, the prosecutors who prosecuted me, or the judges who sentence me, are my enemies. … For hatred is corrosive of a person’s wisdom and conscience; the mentality of enmity can poison a nation’s spirit, instigate brutal life and death struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and block a nation’s progress to freedom and democracy. I hope therefore to be able to transcend my personal vicissitudes in understanding the development of the state and changes in society, to counter the hostility of the regime with the best of intentions, and defuse hate with love.

However, the statement was not permitted to be read in full in court. And on Christmas day, 2009, a Beijing judge handed him an 11-year prison sentence.

It was a devastating verdict, but Liu bore it with stoicism. Then in 2010, while still in prison, Liu was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace for his “long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” His wife, Liu Xia, reported that he wept when told in prison of the news. “This is for the souls of the dead [of June 4],” he told her. Liu Xiaobo read and wrote constantly in prison, but those works — which would have been his most mature — have never been released, and may have been destroyed.

In 2017, Liu died in prison from untreated liver cancer. His death left his wife bereft, the CCP smarting with humiliation, and the world aghast at the Party’s inhumane treatment of this brilliant and idealistic, if insubordinate, Chinese patriot.

“I don’t want to give up either my country or my beliefs,” the Russian political activist Alexei Navalny wrote on Facebook a month before his own death in prison in 2024. “I cannot betray either the first or the second. If your beliefs are worth something, you must be willing to stand up for them. And if necessary, make some sacrifices.”

Liu would have agreed. Like Navalny, he made the ultimate sacrifice for his country and his beliefs.

One of Liu’s most distinguishing hallmarks was his need to confront wrongdoing and mendaciousness wherever he found it, even within himself.

What makes Liu Xiaobo such an interesting thinker, writer and dissident was his constant state of intellectual ferment. While he held firmly to his core principles — justice, fairness, openness, liberty — the hardship and imprisonment he endured seemed to soften rather than harden him. The more repression he suffered, the more self-reflective he became. One of Liu’s most distinguishing hallmarks was the need to confront wrongdoing and mendaciousness wherever he found it, even within himself. “The only route to liberating the spirit,” he once wrote, “is to repent and hold oneself responsible” — exactly what he saw Chinese leaders as almost congenitally indisposed to doing.

While there is no indication that Liu ever became religious, he was fascinated by spiritual writers, particularly St. Augustine, as well as moral rationalists such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Because of his tendency toward self-correction, some critics viewed Liu as inconsistent. But it was this inner search for honesty that conferred on him a quasi-religious quality. Even though he was almost always in a state of opposition and adversity, he cultivated a capacity within himself not just to blame others, but to seek out his own faults and “repent.” And so Liu evolved from an unrepentant enfant terrible during his early years, where provocation seemed to excite him, into a more self-inquiring human being who combined an abiding commitment to humanistic principles with no small amount of hard-earned, almost Christian, humility.

It is true that, over the past few decades, the People’s Republic of China has gained an impressive modicum of “wealth and power” (富强), two aspirations its people have long yearned to attain after a century of weakness and victimization. But this progress has been bittersweet, in which Chinese society has lost important aspects of its humanity — what one might describe as its national soul. By the word “soul” I do not mean a spiritual soul in a religious sense, but in a cultural and ethical sense that embraces those aspects of life beside wealth and power that make us more humane, and our lives more worth living.

By so skillfully limning the biographical and intellectual outlines of Liu Xiaobo’s parlous life, Perry Link and Wu Dazhi have written a work of history that reads almost like literature, a drama not unlike a classical Greek tragedy. After all, Liu’s latter-day odyssey was replete with defiant political pronouncements, courageous actions, overweening aspirations, tendencies towards hubristic arrogance, and a predilection for jousting matches with authority that he was bound to lose. But Liu was also a bold and provocative voice. His repeated detentions and death in prison conferred on him the kind of mythic quality that might have drawn the attention of Euripides or Sophocles as one of their tragic heroes.

Reading I Have No Enemies in the era of Xi Jinping left me feeling as if I was studying the Han or Tang dynasty, exploring a piece of history that happened so long ago it now seems from another world. For while post-1989 China was more tightly controlled than the libertine 1980s, there were still margins of society and channels of communication open for dissenting voices such as Liu’s to find expression. Compared to the current climate of repression, that era now seems like a phantasm.

How the suffocating intellectual environment confected by the CCP ever gave birth to such free-spirited intellects as Liu’s is one of the great mysteries of modern-day China. For despite all the censorship and repression, an impressive number of such liberated minds still manage to arise. Perhaps the real Chinese miracle is not just its impressive economic growth and expansion of military power, but that so many voices have wondrously managed to keep their humanity and love of freedom, and find ways to be heard during this period of political darkness (as also elegantly recorded in Ian Johnson’s recent book Sparks, excerpted in this publication). Link and Wu’s work bears testament to this wonder.

While the book can be overwhelming, it is also immensely enriching. The way that Liu Xiaobo’s life and oeuvre converge with real historical events makes him a guide of sorts through the last four decades of Chinese history. So tumultuous have those decades been. I Have No Enemies gives readers the sensation of whitewater rafting a mythic flume through which both the Yangtze and the Yellow rivers have been diverted.

In the book’s final note, co-author Wu Dazhi writes:

The Chinese people themselves are an endless source of energy and creativity, as unpredictable as they are unstoppable in their quest to build a free and dignified society. Keep watching for new faces. They will be coming.

Indeed, they will. This is a fitting epitaph for a tragic but gripping story. For if there is a single political thinker who embodies the promise and hope for a more humane China to come, it is Liu Xiaobo. His struggle to stay human under relentless Party assault is an inspiration, and his life exemplified the traits that may yet turn China into not just a successful economic story, but a more open, free and tolerant society. ∎

Orville Schell is the Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at Asia Society, and co-publisher of the China Books Review. He is a former Professor and Dean at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of over ten books about China. He is a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, Foreign Affairs and other publications, and has traveled widely in China since the 1970s.