Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Introduction

As Mao’s newly fledged People’s Republic of China came into being in 1949 and the world fell into the deep freeze of the Cold War, a new generation of American China specialists with no prospect of going to mainland China came of age, forced to plumb the conundrum from afar.

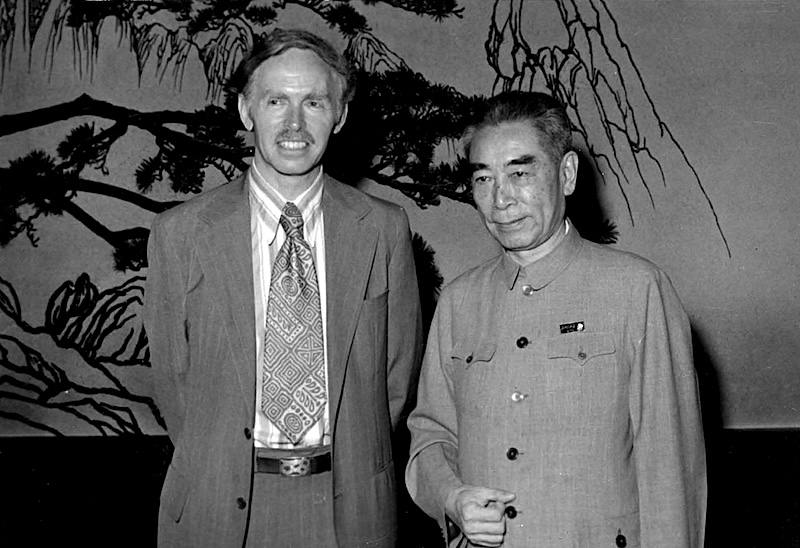

One of the Titans of this decoupled generation was Jerome “Jerry” Cohen, a scholar who pioneered the study of China’s legal systems at a time when most people doubted such a system even existed. His eight decades in China studies took him from Yale and Berkeley to Harvard and NYU; from the U.S., Hong Kong, mainland China and Taiwan to Japan and both North and South Korea; and from scholarship and writing to politics and business. Through these interactions, Cohen had a profound effect on future generations who began foliating the U.S. diplomatic corps, university faculties, think tanks and C-suites.

His elegantly written memoir, Eastward, Westward: A Life in Law (Columbia University Press, 2025), is worth reading not only because it unspools Cohen’s own hybrid life, but it also offers readers a personalized odyssey through the tortured history of the PRC. We are reminded of what a complex puzzle the U.S.-China relationship has been, and what an interesting group of Americans have dedicated their lives to examining its contradictions. In the essay excerpted below, Cohen reflects on a question that has been pivotal not just to his life’s work but to all of ours who have engaged with China: was that engagement itself in vain?

Some thoughtful observers argue that the U.S. policy of cooperation with post-Mao China in developing its legal system has proved a failure. They claim that our engagement from 1978 onward set out to produce a democratic, “rule of law” China that would become, in the eyes of the United States and other democracies, a protector of human rights at home and a responsible member of the world community. Instead, they argue, engagement has enabled a communist dictatorship to become increasingly repressive at home and a threat to world peace and the values we cherish. Implicit in this view is the belief that those of us who sought to assist in the early efforts of former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening policies to improve the legal system of China and its practice of both domestic and international law, were not merely wasting our efforts but, like Dr. Frankenstein, had created a monster. From this perspective, we failed in the effort to export liberal-democratic legal values to China.

How should we evaluate this claim? Would it have been politically wiser if we had not positively responded to the post-1978 opportunities and challenges of helping China to create a legal system from the debris of the 1966–1976 Cultural Revolution?

There is no doubt that foreign efforts to help China reconstruct and develop a legal system in those years contributed to its recovery and its capacity for satisfying the demands of its people. At the time, the Communist Party, China’s government and its people felt the need for the benefits that a decent legal system could provide. The three previous decades of pendulum-like political, economic and social upheaval and transformation had created a chaotic legal vacuum. The country’s new leaders wanted an organized, coherent legal system to help them implement their Leninist rule and carry out the center’s commands. They wished to resurrect China’s pre–Cultural Revolution, Soviet-style system for settling disputes and enforcing official norms, but they believed that a simple return to the Soviet system would fail to meet the country’s modernization needs. The courts, the procuracy, the Ministry of Justice, the law departments of other ministries, the legal profession and even grassroots mediation committees not only had to be revived but also substantially strengthened, and so too did the norm-producing institutions of the National People’s Congress and its provincial and local legislative subordinates.

The educated and bureaucratic elites, having suffered the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, were awaiting some formal assurance of greater personal security. The promulgation of China’s first codes of criminal law and procedure on July 1, 1979, almost 30 years after the regime’s establishment, was Deng Xiaoping government’s first major legislative response to the era of lawlessness that had preceded it. Many believed that the new legislation promised greater public protection against still rampant crime. Others saw it as greater protection against the arbitrary detentions and harsh punishments that had for so long destroyed or scarred so many Chinese lives.

Deng Xiaoping’s goals for feeding an impoverished country and rehabilitating and developing its economy also required immediate legal attention. The transition from a socialist planned domestic economy increased the importance of contracts, new commercial rules and regulations, and the means to enforce them. Buyers, for example, had to be sure that sellers would deliver per the agreed specifications or be made to compensate for their noncompliance. China’s ambitious hopes that Deng’s reform policies would expand foreign trade, earn foreign exchange and attract foreign technology, loans and investment also meant that appropriate norms, institutions, procedures and personnel had to be created. I’m reminded of a moment in 1979, when I asked a member of the Law and Contracts Bureau of the First Ministry of Machine-Building in Shanghai why he was so eager to study law, and his answer was: “Our only problem is that we don’t know anything about either law or contracts!”

Implicit is the belief that those of us who sought to improve the legal system of China were not merely wasting our efforts but, like Dr. Frankenstein, had created a monster.

Among the seven important laws promulgated on July 1, 1979, was the rather vague but symbolically significant Chinese-Foreign Equity Joint Venture Law, which stimulated interest in mastering the mysteries of corporate transactions. In these circumstances, it was widely recognized that legal education and training for various roles would be critical to the success of reform and opening. This meant not only reopening and retooling long-shuttered law schools but also attending to the suddenly large and immediate demand for officials capable of negotiating and implementing contracts, and settling business disputes with foreign corporations, as well as newly evolving Chinese ones. It also meant sending officials, law teachers and advanced students abroad to foreign law schools. Relevant, helpful law had to come from somewhere.

Should those of us who cooperated with China in its sudden hunger for Western law have refused on political grounds? 40 years later, fueled by hindsight, critics now gaining favor in Washington say that we should have realized that our efforts would strengthen an ever more repressive communist dictatorship that is said now to threaten liberal-democratic countries and international security as well as its own people. At the time, however, a government that had repudiated the Cultural Revolution’s killing of several million people and persecution of perhaps 100 million more was seeking our help in using law to prevent a recurrence of that national tragedy.

Even before the July 1, 1979, package of promulgated laws ended a legislative drought of more than two decades, the new, albeit truncated, Chinese constitution of 1978 had reflected the widespread popular revulsion against the violations of human decency and fundamental fairness that had too often marked China’s short history, not only during the Cultural Revolution but also from its inception. And the Chinese people, who were still experiencing the aftereffects of the homicidal, horrendous mass starvation inflicted by the 1959–1961 Great Leap Forward that killed over 30 million people, hungered for the benefits that could be conferred by foreign businesses eager to enter the Chinese market. From the perspective of the late 1970s, it was imperative to help China mitigate the risks of further impoverishment and renewed political chaos.

In terms of international relations, the basis for the Sino-American rapprochement of the 1970s that led to the establishment of bilateral diplomatic relations in 1979 was the value each side saw in jointly opposing the oppressive power of the former Soviet Union. Many analysts also foresaw broader political, diplomatic, economic and other benefits to be derived from finally welcoming China into the world community. Sino-U.S. cooperation in the context of the time did not need to come at the cost of sacrificing to communism the people of Taiwan, who at the time were still suffering under the repression of another Leninist-type but noncommunist regime, the Republic of China, which was dominated by the then recently deceased Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party.

Should those of us who cooperated with China in its sudden hunger for Western law have refused on political grounds?

By the late 1970s, the U.S. government and private U.S. law specialists had long been engaged in supporting the upgrading of the legal systems of both Taiwan and South Korea while they were still under dictatorial rule. That engagement later proved a wise investment. In the late 1980s, when both those societies managed to move toward democratic political regimes, they were bolstered by the more technically proficient and value-enhancing legal systems that U.S. cooperation had already helped establish. Political change and the opportunity it may provide for improvement in a nation’s legal system is unpredictable. Yet change of some sort, however slowly it might appear, is inevitable. “Stop the world, I want to get off” is not an option, even for dictators. During the worst days of the Cultural Revolution, some of us believed that, although China was an unlikely prospect for genuine political democracy in the foreseeable future, the Chinese people might at least foresee development of a legal system that promised them essential decencies and basic protections. In 1979, Deng’s reform policies were beginning to vindicate that belief.

One could not know how much progress the Chinese Communist Party might be willing to make along these lines given its unpromising history, ideology and policies. The 1983 attack against “spiritual pollution” and the subsequent campaign against “bourgeois liberalism” that removed General Secretary Hu Yaobang from Party leadership in 1987 were signals that the legal reforms of Deng’s more open policies might be reaching their limits, at least temporarily. The 1989 downfall of the new Party leader Zhao Ziyang and the following horrendous massacre of June 4 proved a devastating setback. Yet those sad developments were not inevitable, and history might have taken a different turn that would have been more likely to sustain the appetite for legal reform. Despite the impact of June 4, some important legal reforms were achieved in the two decades between Deng Xiaoping’s famous 1992 southern tour and the ascent to power of Xi Jinping in late 2012. Even today, some improvements in the formal judicial system continue to be made amid ever increasing Party and police oppression.

Unfortunately, the system has also organized other sophisticated measures for coercing the Chinese people to comply with the will of the increasingly oppressive Party-state. Party discipline and inspection commissions have subjected many of the more than 80 million Party members to incommunicado detention, during which confessions are often extracted by means of torture, and the police preside over a series of government institutions for inflicting similar administrative punishments on the broader population. The most notorious of these tactics — reeducation through labor — was abolished in 2013, but it has been replaced by a variety of other supposedly noncriminal sanctions, including the confinement of dissidents in mental institutions. In most aspects, the dominant, overwhelmingly Han majority has benefited from law reforms but not from the regime’s use of the legal system to deprive them as well as minorities, such as Tibetans and Uyghurs, of their political freedoms, their personal security against arbitrary punishment, and their resort to independent criminal defense. Thus, our efforts were incomplete even in Chinese terms and surely not largely successful in conventional U.S. terms.

They did help to change China, however — and largely, but not entirely, for the better. There is little doubt that the post-1978 legal reforms with which we assisted helped to make China a stronger government than it might have been otherwise. A less chaotic, more prosperous China was then generally seen to be in America’s interest and in that of the world community, and I believe it still is. Nor should we overlook the fact that, to a certain but unquantifiable degree, the post-1978 legalization effort of the communist regime has come at a political cost to its dictators. Their potential absolute power has been reduced to the extent that the system’s personnel — its legislators, judges, prosecutors, legal administrators, lawyers, scholars and even some officials within the police ministries — constitute an enduring, tacit professional and political interest group that contains significant silent dissenters to the Party’s current repression and its insistence that law specialists serve as instruments of that repression.

Although the lack of transparency within China prevents us from confirming the extent of dissatisfaction among today’s legal elite, many of us receive more than hints of the adverse impact of the past decade’s repressive policies upon this elite. Indeed, my respect for and loyalty to China’s legal specialists who continue to work quietly toward liberal improvement of the system in very difficult and discouraging circumstances is one of my reasons for believing that we should not end our attempts to cooperate with Chinese legal reformers despite the increasingly unattractive political climate for doing so in both the United States and China.

No matter how tightly Xi Jinping now controls the country, his rule will not last forever, and one can then expect another swing of the political pendulum toward a more moderate polity, just as that occurring after Mao’s demise. Spurred by the informed reaction of citizens determined to allow their suppressed resentment to overcome their fear, there will be another attempt to improve human rights protections, permit civil society to recover from Xi-era persecutions and free the country to become less censored and manipulated. When that day dawns, the sustained U.S. and other foreign law reform cooperation that persists to some extent even now in China may be highly appreciated and useful to further progress, as it proved to be in newly democratic Taiwan and South Korea.

Even today, some improvements in the formal judicial system continue to be made amid ever increasing Party and police oppression.

On political grounds, I feel no guilt or regret about the years spent cooperating with China during the halcyon days of the largely optimistic 1980s prior to the massacre of June 4. Nor am I doubtful about the desirability of continuing that cooperation today, as the U.S.-Asia Law Institute at New York University’s School of Law, and other foreign institutions, struggle to do. Helping to reduce the number of wrongful convictions in China, assisting in lessening the amount of time alleged offenders spend in notorious pretrial detention, striving to enhance protections for the country’s embattled human rights lawyers, and promoting the achievement of equal rights for women are useful services, even though success in these efforts may contribute to the stability of the communist regime by alleviating important grievances. As Chinese friends have privately emphasized, the Western effort has reinforced the Chinese people’s longing for “equal justice under law.” I believe in cooperation with the PRC where possible and sensible, while also endorsing competition in economics and even containment, as necessary, in political-military affairs.

We were seeking to meet the needs of those Chinese citizens who were permitted to take part in our legal cooperation programs. Because the United States had emerged as the most prominent political and economic power in the post-World War II era, it was natural that we drew on what we knew from law practice and what had proved successful in our cooperation with other countries. Many meetings with Chinese officials had made clear that, although they were understandably suspicious of our motives and insecure about their lack of international business experience, they were determined to take from us only what they deemed useful for their purposes, not to swallow wholesale what we had to offer. China was no banana republic!

It is true that we failed to achieve our sub silentio hopes that, by helping provide international economic law to meet immediate Chinese needs, we might also promote eventual respect in China for our understanding of the rule of law, the fair administration of justice and the protection of human rights. Certainly, few outside the Chinese Communist Party are likely to claim that China has attained those goals. Nevertheless, the situation today, despite Xi Jinping’s repression, is considerably better for most people — though surely not for Tibetans, Xinjiang Muslims and the nation’s human rights advocates — than it was in the dismal post-Cultural Revolution circumstances that we first encountered in 1979.

History is so adventitious. What if Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang had not been ousted from their Party leadership positions in the late 1980s, or if the People’s Liberation Army, like the East German forces in the same period, had refused to kill its fellow citizens near Tiananmen Square? If we take a long-range perspective, we might say that the jury is still out on the consequences of our legal experiments during the early Deng Xiaoping period. Even in relatively tiny Taiwan, it took decades before the export of U.S. and other foreign laws took full effect. It’s not out of the question that over the long run, and despite the current and ongoing repression, the seeds of something different have been planted in China, that an ever more educated and sophisticated public might demand a more open, less controlled society with greater protections for personal freedoms than China has ever experienced in its 3,000 years of recorded history. If that happens, the work that we did in China in the late 1970s and the 1980s may have left a more indelible, more enduring legacy than it’s natural to assume in the country’s current condition.

The jury is still out on the consequences of our legal experiments during the early Deng Xiaoping period.

From a historical perspective one might ask whether my post-1978 hosts, wittingly or otherwise, revealed some deeper truth about the legal tradition that their country is still coming to terms with. Were they a contemporary embodiment of the quest in China’s 19th-century “response to the West” that John Fairbank and his Chinese colleagues detected many decades ago — the desire to import foreign technical learning solely in order not to dilute, but to preserve, the Chinese essence that they thought was so different from that of the West and more appropriate for them? Does this help explain why China has thus far successfully imported and adapted much of Western law in the cause of economic development but failed in other respects to practice Western versions of the rule of law, the administration of justice and the protection of political and civil rights?

What indeed is the Chinese “essence” regarding law, at least on mainland China, if not Taiwan? Is it subject to significant change in response to future internal developments, foreign stimuli, or both? To what extent should this familiar Sinocentric interpretation of events be leavened with recollection of the initial profound shaping of the Chinese legal system by the long-departed Soviet Union? The leaders of today’s China, while seeking to exhume Confucius and the Chinese “essence” on behalf of nationalism, continue to extol Marxism despite its Western roots. Yet they are often reluctant to acknowledge the abiding Soviet impact on their legal system from Joseph Stalin’s grave, except to invoke the fate of the former Soviet Union as a feared negative example.

Despite Chairman Mao’s attempt to exclude the influence of the pre-1949 Republic of China on the People’s Republic of China (PRC), should we also take into account its inevitable impact, as well as that of the Japanese and German systems to which the PRC often looked? And what of the unacknowledged but significant influence of Taiwan, which still purports to be the contemporary, democratic manifestation of the Republic of China? Should we regard the contemporary PRC legal system as an uneasy, evolving, contentious amalgam of traditional Chinese, Soviet and Western elements?

What is at stake, in our collective quest to answer these questions and to understand China, is more than the theoretical and practical benefits to be derived from the detached academic study of comparative law. I like to believe that my perhaps excessive passion for the subject of arbitrary detention involves not so much personal ego as recognition of the need I hope we all feel to extend to Chinese people the benefits of “equal justice under law.” Core among those benefits is protection against the cruelty and injustice of arbitrary detention, wherever it occurs. That is why I have emphasized my sympathy for all the victims of China’s increasingly sophisticated repression. ∎

This essay (originally titled “Was Helping China Build Its Post-1978 Legal System A Mistake?”) is excerpted from Eastward, Westward by Jerome Cohen, ©2025 Columbia University Press (used by arrangement with the publisher, all rights reserved).

Jerome A. Cohen is an American legal scholar focused on Chinese law, and an advocate of human rights in China since the 1970s. He is professor emeritus at New York University School of Law, and an adjunct senior fellow for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. Cohen is the author, co-author and editor of several books on Chinese law, and most recently the memoir Eastward, Westward: A Life in Law (2025).