One of the questions I am asked most often is what it feels like, as a China scholar, not to be able to go to China. I have been denied visas since 1996. I do not know the reason (the authorities won’t specify), although I can see that the number of possibilities is large.

On the evening of July 8, 1996, I arrived at the Beijing Capital Airport after a long, two-stage flight from Newark, New Jersey. I was ready to see friends who were waiting for me outside the airport, but more than anything I needed sleep. In those days the Beijing airport still bore some of the quaint flavor of China’s Mao era: drab walls, ceiling fans, luggage carousels built of wooden slats. The spanking new construction that came with the city’s hosting of the 2008 Summer Olympics had not yet arrived.

Passport control did have new computers, and when my turn in line came, a young officer squinted at his monitor, rather longer than one would think he had to, and then told me in halting English to take a seat and “wait a moment.” About an hour later, another uniformed man, middle-aged with a long, serious face, returned to say, in Chinese (apparently, research on me during the hour had revealed that I could speak Chinese), that “we have checked with our superiors and you are not welcome in our country.” I mumbled that I had a Chinese visa and asked what the problem was. He said nothing. He pointed an index finger toward the ceiling and fixed me with a look.

It was late in the evening, and there were no return flights to the U.S. until the next morning. This made me a problem for him and his colleagues, whose need to come up with a solution can explain at least part of my hour-long wait. In the end, four young plainclothes policemen accompanied me to the United Airlines ticket counter. One of them, with a crew cut and bushy eyebrows, was the leader, and showed some enthusiasm for that role. He seemed new in it. He told the United agent on duty that the airline had brought into China a passenger whose papers were unacceptable and that the airline would have to provide a hotel room for one night. United, which apparently had a policy of just giving in when such matters arose, paid for a room at the nearby Mövenpick Hotel, and the four young policemen and I went there to spend the night. Officially, I had not entered China.

The young policemen smoked, and I do not, but other than that I suffered no mistreatment. As I was brushing my teeth the bushy-browed leader read to me in English the formal police language that it was his duty to read: “You cannot leave the hotel, you cannot leave our company, you cannot make a phone call,” and so on — about eight items in all. The phone-call rule was the relevant one, because my only request to the police had been to call my friends who were waiting for me outside the airport. I wanted to tell them to go home and not to worry. But the policeman said this was not permitted and, to emphasize the point, had the others unplug the telephone in the room and place it beneath the pillows on one of the beds.

After the official rules had been read, the speech of the four young policemen shifted to an informal register. We switched to Chinese, which seemed to relax them. They expressed puzzlement that my Chinese tones were correct (“How did that happen?”) and then moved on to questions like how much my watch cost. They were glad to be with me in the Mövenpick, because the police system provides meal coupons for overtime work, so tonight they had a special opportunity to eat in the fancy restaurant on the ground floor. It was past 11:00 p.m., but never mind; they wanted dinner. They asked me to come down with them. I teased them by asking whether they had a free-meal coupon for me, too. “Oh, no sir!” they said (when speaking informally, they were deferential), “but you can buy your own.” I was not hungry and told them I did not want to eat. That created another problem. I was not allowed to leave them, which meant they were not allowed to leave me, either. They solved the matter by taking turns. Three of them went down to eat, while one, smoking and chatting, stayed with me. When the three came back, that one went down.

The next morning they took me back to the airport and to the United counter for check-in.

“The flight is full,” said the agent.

“If this passenger is not on the flight, the airplane will not leave the airport,” the leader said. I doubt that this was an idle threat. In any case, United did find me a seat, and I headed back to Newark.

A uniformed man, middle-aged with a long, serious face, returned to say that ‘we have checked with our superiors and you are not welcome in our country.’

“Congratulations,” said Liu Binyan, the distinguished Chinese journalist who was living in exile in New Jersey at the time, when I told him of my turn-around in Beijing. “Now you know what it feels like to be Chinese.” He said that my rejection at a physical border had actually ushered me across a cultural border. For decades, the authorities in China had been telling intellectuals whom they wanted to control that “you are wrong and here is your punishment; it is now up to you to reflect on your errors and to write a confession.” Liu saw me in that position as well.

I began searching my mind. Which of my “errors” might be the one that precipitated the regime’s decision? I had written about censorship and repression in China, had translated dissident writers, and had joined human rights groups. But exactly what line had I crossed, and where? I asked Liu Binyan and other Chinese friends to help me guess. Some said it must have been because, the day after the Tiananmen Massacre in June, 1989, I had given a ride to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing to Fang Lizhi and Li Shuxian, professors of physics and a married couple, whom the government viewed as “black hands” behind the pro-democracy movement. Fang and Li were offered refuge in the embassy and stayed for 13 months. This was an embarrassment to the Chinese authorities, who blamed the U.S. for “meddling in its internal affairs.” All this would have made me a major meddler, my friends said.

This theory makes good sense except that it does not explain why I was able to travel to China six times between 1989, when the massacre happened, and 1996, when I was turned around at the airport. I spent the entire summer of 1994 in China as field director of Princeton in Beijing, an intensive summer Chinese language program that my Princeton colleague CP Chou and I had established the year before. When I left Beijing at the end of that summer, four policemen met me at the airport to give my luggage a thorough inspection for 20 minutes. (They were especially interested in my address book.) But other than that, I had no political trouble that summer, and I visited Beijing again in 1995.

So the question becomes: what happened in 1994 or 1995 that caused a change? Some of my friends have guessed that it was because 1994 was the year when I agreed to serve as Chair of the Board of the Princeton China Initiative (PCI), an umbrella organization that had raised funds to provide temporary homes, physical and intellectual, to refugees from the 1989 crackdown. The group included some who were still on Chinese government wanted lists. My position as board chair was pro forma. I felt like a figurehead accepting the title — but I did accept it, because the group needed an American for legal purposes. Was I blacklisted because, in Beijing’s view, I was now head of a counterrevolutionary camp? Some of my friends in PCI thought so.

Others noted that 1994 was the year President Bill Clinton decided to “de-link” human rights from trade in his China policy. In the early 1990s, the U.S. had used the granting or withholding of “most favored nation” trading status to pressure Beijing for human rights concessions; after 1994, Beijing was given Permanent Normal Trading Relations, and the pressure disappeared. It might be, my Chinese friends speculated, that Beijing now saw that they could handle small fry like American human rights advocates pretty much as they liked, with no fear of consequences.

Still others of my friends thought (and this would be my guess, too) that the 1989 incident with Fang Lizhi was still the reason, or at least the main reason, and that it had taken the Chinese leaders a few years to decide to punish me for it. In 1989 I had been director of the Beijing office of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS), and the Beijing authorities, thirsty for Western science to bolster its catch-up efforts in technology, and for that reason not wanting to jeopardize its relationship with the NAS, probably held its nose and tolerated me until, in 1994 or 1995, it seemed safe to levy punishments.

Which of my ‘errors’ might be the one that precipitated the regime’s decision? Exactly what line had I crossed, and where?

After 1996 I tried and failed several times to get visas. I never tried just for the sake of trying. I tried only after receiving invitations to attend conferences or to give lectures. In each case my Chinese hosts issued invitations, after which I applied and then was rejected.

In 1999, a highly-placed Chinese official who used the pseudonym Zhang Liang carried out of China a trove of government documents that related to the June 4 massacre in 1989. He gave them to my friend Andrew Nathan, a professor of politics at Columbia, and Nathan asked me to help translate and edit the documents into an abridged English version. I agreed, and the book appeared in 2001 as The Tiananmen Papers (PublicAffairs, 2002). By the time it was finished I had become friendly with Zhang Liang (who does not want his real name publicized, even now), and I asked his advice about my visa problem. He said that a matter like this would need to be addressed at the highest levels in China. If I would write a letter to China’s premier, Zhu Rongji, he could get it into Zhu’s hands.

In December 2002, I addressed a letter to Mr. Zhu in both Chinese and English versions. I explained who I was and said that I would like to travel to Beijing in summer 2003 to work on the Princeton in Beijing language program. I wrote that I hoped that he would share my view that “to train young Americans to speak Chinese, write Chinese, make Chinese friends, and understand Chinese daily life is an extremely meaningful mission.” A few months later Zhang Liang called me on the telephone. He was ready to give me an oral report on the response to my letter.

Zhu had read it, he said, and had written at the bottom (the following words are not a direct quote; they are based on my memory of the phone call): “Please check to see if Perry Link really is a scholar, and if he is, my opinion is that he should be allowed to come to China.” Then, said Zhang Liang, Zhu forwarded the letter, with his opinion appended, to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and Ministry of State Security (MSS). MFA relayed the matter to the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., where officials looked into the matter. MFA’s reply to Zhu was that, yes, Link is a scholar and MFA has no objection to his coming to China.

The reply from MSS was much lengthier and ended by saying (again, from my memory of the phone call) that “in view of the continuing complexity of the international situation, it is our view that Link and the 17 others should for the time being not be allowed into China.” This told me two things. First, somewhere in the world, 17 others were on the same blacklist as I. Second, MSS outweighed China’s premier on such questions.

In fall 2013, the Chinese government inadvertently allowed me a glimpse into how the Ministry of Culture, too, defers to MSS. I was doing research at the Academia Sinica in Taiwan when, out of the blue, I received an email from a man named Zhou Yong, First Secretary of the Cultural Office of the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., who was inviting me, all expenses paid, to a “Forum of Overseas Sinologists” that was to be held in Beijing in December of that year. The Ministry of Culture was the host. A number of first-rate Chinese intellectuals were also being invited, so I was interested. I wrote an email, in Chinese, directly to the forum organizers in Beijing, reminding them that I had been denied visas for many years — were they sure they could invite me? That email brought no response, which I took as neither good news nor bad. I then followed up with Zhou Yong, who responded with enthusiasm and urged me to attend.

I told him I was in Taiwan and asked how I could get a visa (one cannot get mainland visas in Taiwan). Zhou suggested that I go to Hong Kong for one. But I did not want to do that, because I remained skeptical that a visa would actually be forthcoming and did not want to spend time and money in vain. I asked if I could send my passport to Washington by express mail and let him and his colleagues stamp the visa there. Mr. Zhou looked into the request and wrote back, “Though it’s tricky, finally it could be handled as you wish.” He even offered to fill out parts of the visa form for me and to pre-pay the fee, saying that I could repay him later. So I mailed my passport to Washington. Later that same day, November 8, Mr. Zhou sent another email: “After review, I’d like to inform you that you will not be invited to the forum. I’ll have your passport sent back to you as soon as possible.”

I replied that I would be sorry to miss the forum but would like to maintain my visa application anyway, because I would like to do some interviewing in Beijing and Tianjin on my current research project on Chinese comedians’ dialogues (相声). (I was indeed doing research on comic dialogue — not delivering a satiric comment on our email exchange.) I actually felt some sympathy for Mr. Zhou. He had, after all, only been doing his job. A mistake inside his government’s bureaucracy — someone’s failure to check with MSS — had blindsided and embarrassed him. The evaporation of my invitation must have been more surprising to him than to me.

Zhou had always answered my emails promptly, but this last one — about my request to maintain my visa application anyway — brought no reply. Nine days later, November 17, I still had no answer, and no passport, so wrote again: “Dear Mr. Zhou: Have you received my passport? Please tell me where things stand.” Still no answer. By chance the passport did arrive the following day, so I wrote once more, “Dear Yong, I understand that you work for an authoritarian government and do not have the freedom to answer my emails once you have been told to cut off. This is not your fault, and I do not blame you for it. My passport has been received. Thank you for sending. Best, Perry.”

Somewhere in the world, 17 others were on the same blacklist as I.

I can understand why Chinese authorities do not like my opinions and the candor with which I sometimes state them. But there is something else they don’t like as well. It is a subtle matter, but is telling in its implications and therefore worth a short detour here.

Chinese culture usually welcomes outsiders in proportion to how much they are willing and able to look, sound, and act Chinese. It is, from one point of view, a presumptuous attitude, because it seems to assume that being Chinese is the best way to be human. But it is also a generous approach in that it offers any human being the route to Chineseness if he or she wants to take it. A white Caucasian like me cannot easily look Chinese; but to sound and act Chinese remains possible and can make a big difference in how well a person fits into Chinese daily life. I was born with a knack for imitating sounds, and my first teacher of Chinese, at Harvard in 1963, took advantage of that knack to drill Chinese tonal pronunciation into me. On the telephone, Chinese people are sometimes dubious when I tell them that I am not Chinese. I have even been accused of lying about it. Face-to-face, it is obvious that I am not Chinese, but the boundaries between “you” and “us” melt away faster when oral exchange begins. This effect is visible whether or not the context is happy. It made a difference when I met in Princeton with Chinese refugee-dissidents who were seeking Princeton’s help; it made a difference, too, when I was in the Mövenpick Hotel with four policemen whose job it was to watch me.

The issue matters for the blacklist question because China’s communist authorities, differently from the culture at large, are strongly averse to seeing foreigners get “inside” their world. They want the borders of their world to be impenetrable, and foreigners who sound too Chinese make them nervous. They would rather deal with foreigners who either speak no Chinese or, if they do speak it, speak it badly enough that the line between “you” and “us” is obvious. Once, at a luncheon for a visiting Chinese delegation at UCLA, where Americans and Chinese were speaking through interpreters, I decided to ask a question directly in Chinese, without the interpreter. The head-of-delegation from China was visibly discomfited. He was on the spot. What should he do? After an awkward moment he turned to his interpreter and waited for her near-verbatim repetition of my question. In form, after all, she was the person who was supposed to be speaking Chinese to him. Waiting to funnel the message through her was not done to improve clarity; it was more nearly a political reflex, whose purpose was to maintain the border between “our side” and “your side.”

In short, I believe that for people in the CCP regime, who do not like it when I do things like help Fang Lizhi or co-edit The Tiananmen Papers, it only makes things worse that I sound like a Chinese person orally. It makes me seem slicker, more sinister, and more likely to have been trained in the CIA. (The latter point is ironic, because it is well-known in the Chinese-teaching field in the U.S. that CIA schools do not stress training in tonal pronunciation.)

China’s communist authorities would rather deal with foreigners who either speak no Chinese, or speak it badly enough that the line between ‘you’ and ‘us’ is obvious.

People ask if being blacklisted ever makes me regret my choice to spend my life studying China, the country that bars me. Do I feel at some level betrayed? Oddly, perhaps, I have never felt that way in the slightest. I am so distant from that feeling that I almost cannot understand it. Most obviously, this is because I have never thought of the people who have blacklisted me as representing China. They are only one small (and especially ugly) part of a much larger and more various entity. Do farmers in Guizhou view me as persona non grata? Miners in Anhui? I can’t imagine it. Even the list-makers’ minions — the young policemen who detained me at the Beijing airport or the hapless Mr. Zhou in the Chinese embassy in Washington — are different from the list-makers themselves. Would these people have barred me, if it had been up to them? I doubt it, but they are “China” just as much as the men they work for.

China is history, language, fiction, poetry, food, humor, scenery — and on and on. My wife and most of my best friends in this world are Chinese. The harm that the blacklist-makers have done to them, and to countless others whose fates I have been able to observe, directly or through writing, makes the harm done to me about as heavy as garlic skin. Without, of course, intending to, leaders of the CCP have given me deeper understanding of certain human values — truth, freedom, integrity — than, perhaps, I could have reached in a world lacking the CCP.

There are two main reasons why I wish I were not on a blacklist. One is that I miss China’s life on the ground: the sounds, sights, and smells of the streets, the charming snacks that can be had there, and the lively, authentic speech. My 2013 book, An Anatomy of Chinese: Rhythm, Metaphor, Politics (Harvard University Press) is about contemporary Chinese language and draws examples not only from published writing but also from T-shirts, graffiti, slang, jokes, and other ephemera that I could collect easily during times I spent in China but since then can gather only second hand. I also miss face-to-face encounters with writers, scholars, activists, booksellers, and people on the street. But such losses are not as severe as one might fear. I can meet people when they come out of China, and, thanks to email and the internet, can stay in touch intellectually without much difficulty.

The second cost of being blacklisted troubles me more. It is that blacklisting turns me into a tool of the Chinese government in its efforts to impose self-censorship among Western students and scholars. My blacklisting became well known in China studies after 1996, and since then I have had many inquiries about it, especially from younger scholars. In one way or another they ask, although always politely, “How, Professor Link, do I not end up where you are?” A bright Princeton undergraduate, who had studied Chinese language with me, was delighted to tell me that she had secured a summer internship with Human Rights Watch. A few days later, after hearing of my blacklisting, she came back to ask, “What did you do?” I told her the truth, of course, which was that I did not exactly know, but I also tried to assure her that something as innocuous as a summer internship at HRW should be no problem. She came back a few days later to tell me that she had declined the internship. She thought it too big a risk; she might want a China career later.

Around the same time, a Ph.D. student came to consult me about his dissertation topic. He wanted to write on Chinese democracy, but his advisers in the politics department were cautioning him that this might not be a smart move. What if it cost him his access to China? The young man chose a different topic. Were his advisers wrong? From one point of view, no, they were not. Unclarity about where red lines exactly are, when magnified by fear, makes self-censorship even more constricting than conventional censorship. Another Princeton student — a president of the undergraduate student body, who had been invited to China along with other Ivy student presidents — came to ask me whether, while in China, he could even utter the words “Dalai Lama.”

I could tell many other stories of how China scholars, including senior figures, stay away from public comment on topics that Beijing considers “sensitive.” When they do need to touch on them, they choose their phrases carefully. A term like “Taiwan independence,” anathema to Beijing, is avoided in favor of “cross-strait relations” or “the Taiwan question.” The June 4 massacre of 1989 is demoted linguistically to an “incident.” Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize winner who sat in prison before he died in 2017, is not mentioned at all, if possible.

It is not quite accurate to say that China scholars are either naïve or cowardly in accepting these verbal accommodations. Their ways of speaking are a sort of professional code that the field understands as code and that does not color — at least not very much — the underlying grasp of issues. The costs of using the code are most heavy when experts turn to address students or the public. Audiences not privy to the code can be given the impression that a massacre was only an incident; that Taiwan independence really isn’t much of an issue; and that a Nobel Prize winner in prison may not be worth mentioning.

The avoidance of straight talk with the public is, in my view, a violation of the tenure system. A tenured professorship is a wonderful job: a person gets respect, social status, and a guaranteed upper-middle-class lifestyle all the way to the grave. Why does society give us such a good deal? Because we are nice people? Because we have already worked hard and so deserve guaranteed groceries for life? No. Society gives us the good deal so that we can tell the truth as we see it, without fear or favor. Tenure protects us so that we can do that. What we owe society in return is candor. If we hem and haw, pull punches, and are otherwise “prudent” about telling the truth, we renege on the tenure deal.

Blacklisting turns me into a tool of the Chinese government in its efforts to impose self-censorship among Western students and scholars.

People who ask me about my blacklisting usually don’t imagine that there are benefits to the status, but there are. Again, I will name two.

One is that a person gets undeserved credit. It embarrasses me to hear people say, “You were so courageous to help Fang Lizhi on the day of the massacre.” The events of that day had stunned me into a state of mind where my decisions were neither courageous nor cowardly but simply reflexive. “We need a ride; can you help?” “I think so; let me try.” That was it. No courage involved.

The congratulatory views can be surprising. In 2008, shortly after I arrived at the University of California at Riverside to teach, I was walking across campus one day when a young blond male on a skateboard came careening my way. He jumped off in front of me and neatly flipped the board upward with his foot to catch it in his right hand.

“Professor Link!” he said.

“Yes…?”

“I hear you’re on a Chinese government blacklist!”

“Yes, that’s right…”

“Dude!” he shouted, gave me a thumbs up, and skated off.

The second benefit of being blacklisted is more important. It is that blacklisting leaves a person freer than before. This is because once a blacklisting happens, the fear that it might happen disappears. After all it is dread of the event — not the event itself — that causes people to self-censor. Relieved of the pressure, it becomes much easier to say what one thinks. My favorite expression of this principle is the Chinese farmers’ proverb “dead pigs aren’t afraid of hot water” (死猪不怕开水烫). A dead pig not only enjoys maximal latitude to comment but can be of service to others. In 2015 the Dalai Lama was interested in having a small meeting with American China scholars, and the scholars whom the Dalai Lama’s office approached showed strong interest. But the question of who would host the meeting became a problem; to do it would be to risk blacklisting. Someone called me to see whether I could help. I would not need to raise money or do any organizing — just be the official host. I agreed. Why not? A second death would be redundant.

Some people have tried to help me get off the blacklist. I have already noted how the compiler of The Tiananmen Papers tried. In 2010 a reporter named Shi Feike, from China’s liberal-leaning Southern News Group in Guangzhou, interviewed me in depth during a trip to the U.S. He did an excellent write-up of the interview, but it had to be cut by more than half before it was published. He knew that the cutting would happen, but felt that just to have my name, photo, and some of my words appear in the mainland press would be a worthwhile step forward, both for China and for me. He wanted, he said, to help me tuomin (脱敏), literally “depart sensitivity,” in the mainland press. Americans have tried to help, too. In 2008 a group of 18 prominent China scholars wrote a private letter to the Chinese government advising that the blacklisting of American scholars is harmful to both the U.S. and China.

When is it right to make some compromises in order to get off of blacklists? Exiled Chinese dissidents have sometimes agreed to terms in order to make home visits for pressing reasons, such as the funeral of a parent. Americans, too, have sometimes succeeded in getting off blacklists, with or without making concessions. I would make concessions if I had a reason as strong as the death of a parent, and I find it hard to make blanket judgments about how any person should or should not play Beijing’s unpalatable game. For me personally, though, the prospect of remaining on a blacklist has so far been preferable to acceptance of made-in-Beijing adjustments. ∎

This previously unpublished essay is excerpted from The Anaconda in the Chandelier: Writings on China, by Perry Link (Paul Dry Books, 2025). © Perry Link. Used by permission of Paul Dry Books, Inc.

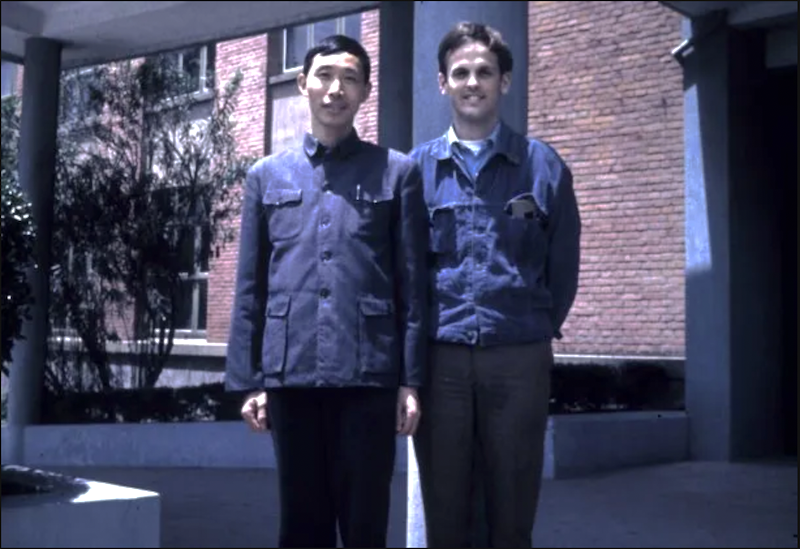

Header: Paul Dry Books. All other images courtesy of Perry Link.

Perry Link is Professor of Comparative Literature/Chinese at University of California, Riverside, and Professor Emeritus of East Asian Studies at Princeton University, specializing in 20th-century Chinese literature. His publications include The Uses of Literature (2000), An Anatomy of Chinese (2013) and, most recently, I Have No Enemies (2023). He is a regular commenter on Chinese society and politics, at The New York Review of Books and elsewhere.